Hans van Rappard

10 ― From: Rappard, H. van (2009). Walking Two Roads ― Accord and Separation In Chinese and Western Thought. Amsterdam: VU University Press. Chapter 4, pp. 115-124.

Enriched edition with illustrations and with the author’s permission.

part 1 – part 2 – part 3 – part 4 – part 5 – part 6 – part 7 – part 8 – part 9 – part 10 – part 11 – part 12 – part 13 – part 14 – part 15 – part 16 – part 17

Introduction

It was previously observed that next to the Yijing three broad movements have by and large determined the course of Chinese philosophy.

Confucianism and Daoism having been examined with a view to what I believe is the central aspect of the way of life proposed by them, it is now time to turn to the third movement, Buddhism. Just as in the case of Confucianism and Daoism ― and Hellenistic philosophy come to that ― the daunting scope of the topic will have to be reduced to manageable proportions.

Our treatment of Buddhism will therefore be limited to the two schools that are generally perceived as typically Chinese, the Huayan and the Chan schools. But first we need information on the development of Buddhism in China and its basic formulas.

Development of Buddhism in China

In the first century BCE China conquered parts of Central Asia, where a century before Buddhism had spread. Thus, China became the first East Asian country to be penetrated by this relatively young Indian religion.

The first monastery was established towards the end of the second century CE when the Han dynasty collapsed. In the three troubled centuries that followed, Buddhism managed to settle and develop into a widely accepted school that enjoyed the favours of several emperors.

Around 400 CE, hundreds of writings had been translated into Chinese and by the beginning of the sixth century Buddhism had been firmly established throughout the country and spread its message via countless monasteries and temples.

This was no mean feat for an alien religion whose tenets ran in many ways against the most deep seated sentiments of its host country. The monkish school seemed quite indifferent to the perpetuation of the core of the Chinese social system, the family, it did not always pay respect to the emperor and to many seemed to preach baseless superstitions of which the reincarnation doctrine especially stirred up disputes. Nevertheless, Fairbank observed,

“In the great age of Buddhism in China from the fifth to the ninth centuries, Confucianism was largely left in eclipse and the Buddhist teachings as well as Buddhist art had a profound effect upon Chinese culture”.[2]

Buddhism brought a message that was not available from the indigenous teachers. Many Chinese got attracted to the Bodhisattva ideal, which entailed huge promises for everyone regardless of social status, while merciful deities like Guanyin (Quan Yin) provided a kind of comfort that was not on offer from Confucians or Daoists.

Similarities between Buddhism and Daoism

The rise of Buddhism coincided with a revival of Daoism and many Chinese began to see similarities between the two schools. East Asian religion at large tends to be syncretistic in any case and few doubted that the truth handed down by their own sages and the Buddhist one were basically the same.

Until the fifth century many Daoists considered Buddhism just another way towards the goal that they also envisioned, while an earlier adherent had taken the outlandish religion as the result of a conversion of the barbarians by Laozi.

Another example of the close relation between Daoism and early Buddhism is provided by a former Daoist, who after his conversion to Buddhism kept on using the Zhuangzi to explain his new persuasion, while others used the Laozi or the Yijing. In the early days of the new religion Buddhist monks were often called or Dao-people, while the Daoist worldview was calmly read into the Buddhist doctrine. This has cast a long shadow.

At least until the Communist takeover, to the average Chinese Daoism and Buddhism simply amounted to the same.

Translation of Buddhist texts, liberally using Daoist terms

The relations between Daoists and Buddhists were much strengthened by the translation of Buddhist texts, liberally using Daoist terms whose meaning was then to some extent carried over to the translations. But this was probably not unique to Buddhism.

Lloyd and Sivin show that Chinese scientists, as different from their competitive Greek colleagues who tended to redefine terms or coin new ones,

“adapted or combined familiar words to fit new technical contexts, which their older meanings still influenced”.[3]

Be this as it may, in the fourth and fifth centuries much of the basic terminology of Buddhism was considered to be more or less equivalent to that of Daoism and this did not wear off during the subsequent centuries. Daoism has always kept a closer relation with and exerted far more influence on Buddhism than Confucianism. But the latter made itself also felt in the translation of the Buddhist texts if only because great care was taken to avoid terms and phrases which might offend the Confucian sense of propriety in matters as family ethics and the attitude to social superiors.

Clearly, Buddhism, called a barbarian religion by the ethnocentric Chinese adapted itself quite well to its host country and over a couple of centuries managed to assume a highly Chinese form.

This is particularly clear in the Huayan school, sometimes called the philosophical apogee of Chinese Buddhism and also in the Chan school, which is often deemed the most typically Chinese form of Buddhism. We will turn shortly to these schools. But first we should go into the basic tenets of the alien religion.

Basic Buddhist formulas

When it was introduced in China, Buddhism had already evolved its Mahayana form. This development is called the second turning of the wheel, the first turning being the sermon delivered by Buddha on his enlightenment in the deer park near Benares.

Although according to its Tibetan followers Buddhism saw yet another turning of the wheel when in the eighth century it settled in the country of snows, its basic formulas have remained virtually unchanged. Two of them have already been treated in an earlier paper but will be presented here again to situate them in the larger picture sketched below.

The Four Noble Truths

The first and best known formula is the Four Noble Truths, comprising

- suffering (dukkha),

- the arising or origin of suffering (samudaya),

- the cessation of suffering (nirodha), and

- the way leading to that end (magga).

One is struck by the central position of suffering. Suffering is an unpleasant word. Does the formula entail that Buddhism teaches that human life is nothing but suffering, a relentless succession of misery and illness without the slightest glimmer of joy, disease without pause?

Buddhism has indeed been interpreted along such lines, especially in the early years of its coming to the West. But this is a superficial interpretation; so superficial in fact that that it is downright misleading. True enough, the ordinary meaning of the Sanskrit word dukkha is suffering, pain or misery but, though not denying these features its Buddhist meaning is far deeper, wider, and subtler.

Human life is seen as essentially frustrating and unfulfilling. Of course, we all have to face deceptions, illness, and death but more often or rather, virtually always our suffering is subtler and seemingly lighter to bear.

Even when one is not faced with any particular problems one still tends to be plagued by a nagging sense that things are not quite as they should be. However elusive to come to grips with, there is a pervasive feeling that something is lacking, something is wrong.

‘I do not have enough, I am not treated well enough, I am not liked enough, I …’. Indeed, ‘I’.

All this can be traced to the impossibility for the illusive I to ever secure for itself ‘enough’. But the meaning of suffering is even deeper. Buddhism does not deny happiness in ordinary human life. Yet, this too, is ultimately seen as suffering and more than that, the spiritual happiness that may be the result of meditation is also included in it. This is so because even the highest happiness, just as its more humdrum kinds, is after all but impermanent. It does not last, and this feature happiness shares with everything else under the sun.

Three Signs of Being

Impermanence

The Noble truths will again be encountered below. At this juncture we leave them because an auspicious point has been reached to introduce another formula. Impermanence is one of the Three Signs of Being, the other two signs being suffering and no-I. It has just been pointed out that impermanence and suffering are closely linked.

A happy feeling, however lofty its cause, won’t persist. Sooner rather than later it wears off. Feeling great does not last, while something we have will eventually be lost or fall to pieces and this holds for even the highest bliss.

Suffering

Impermanence, in other words, will ultimately nullify every prop the beleaguered ego may hope to shore itself up with ― and this is the be-all and end-all of suffering. Incidentally, the fact that suffering, the first Noble Truth, should also obtain among the Three Signs suggests that the formulas are interconnected.

This is not surprising since, as pointed out previously, Buddhism is highly interlinked. But it should not be concluded that all the formulas together allow of systematisation because this would entail a way of linear, causal thinking that is completely alien to Buddhism. The various formulas do not refer to different things that may be put in a neat order because one causes the other. Rather, it is crucial to understand that they all point to the very same thing though in their own specific way.

No-I

And this brings us quite fittingly to the third Sign of Being, no-I, because it is to this sign that everything in Buddhism refers.

To clarify the sign of no-I we return to the formula of the Five Aggregates, comprising

The Five Aggregates (skandha)

- body,

- feeling/sensation,

- perception,

- mental/volitional formations

- consciousness.

As observed in paper 5, the aggregates teach a couple of points. The first links up with the sign of impermanence, and thus also with suffering, because the aggregates are not to be thought of as static things but as energies. As such they happen to sit well with the central feature of Chinese science discussed in paper 2.

Yin and yang, the five phases (wuxing), and the Yijing or Book of changes entail a view of world and man that is characterised by the words energy and change. The Five Aggregates too undergo continuous change. This process goes on relentlessly ― from moment to moment and more than that, also from life to life, an endless coming to be and ceasing to be occurs.

The aggregates describe the human being as a bundle of aggregates

Moreover, and this brings us to the sign of no-I, the aggregates describe the human being as a bundle of aggregates.

As mentioned in paper 5, paper 6, the emphasis is on the word ‘bundle’, which implies that no aggregate in particular is privileged as the central one and thus there is no room for a ruling instance or hegemonikon, as it was called in ancient Greece.

In other words, there is nothing like a central governing ego, or as Buddhism says, there is no I. The aggregate that comes closest to what we are used to think of as I, ego, or self is that of the volitional/ mental formations (sumskaras), comprising all mental functions except feeling/ sensation and perception, which depend on direct contact: an unpleasant feeling/ sensation is immediately perceived and recognised as a headache.

But as long as this perception activates no volitional/ mental component, no ‘wishful’ thinking ensues. Most often however, the volitional/mental formations do get fired and since they are made up of past impressions, memories, conditionings, etc. they distort and becloud the aggregates of perception and consciousness. The samskaras are of crucial importance because it is in them that the reason is found why we habitually transcend the present moment.

Karma

When fired to intentional thought, speech, or action they will prompt mistaken, one-sided ideas, words, or behaviours and thus instigate karma.

The Sanskrit word karma (from the root kr, to do) means action or doing but in Buddhism it refers specifically to volitional, intended deeds, which can be carried out in thought, speech, and of course action.

For instance, when I am angry with someone and plan a nasty trick to get even, this involves firstly, a volitional impulse to pull a fast one and secondly, its execution.

In other words, for thought, speech, and action to be intentional and thus karma productive they have to be wilful ― if not, they are neutral. After all, it is the fires or appetites that provide the energy that drives us around the constantly changing states of the heart-mind in an endless round that makes up our daily life.

Eight kinds of consciousness

The crucial point is that the volitional impulse, an element of karmic energy, is dropped into the mental stream but remains dormant. To explain this phenomenon a later school, the Yogacara, developed in the fifth century CE in India divided the heart-mind into eight kinds of consciousness.

Next to the six kinds treated in paper 5 there are two additional ones.

- The seventh consciousness (manas) is what Takakusa describes as the thinking and willing ‘individualising centre of egotism’, while

- the eighth consciousness (alaya), the ‘storing centre of ideation’ is the depository in which the ‘seeds’ (bija) of all perceptions are kept.

The stored seeds are latent energies, which may later be actualised in new perceptions. The alaya is thus the seed-bed of all phenomena, that is, the things and events in the world as perceived by us. In other words, ultimately our world issues from perception or consciousness and the basic tenet of the school is therefore called the ‘perception only’ or ‘(heart-)mind only’ doctrine. What happens when something is perceived, Takakusu says, is that certain seeds that were hitherto latent in the alaya

“sprout out into the object-world”, causing their manifestation to be seen.[4]

But the reflection of this perception produces new seeds to be stored, which in their turn will sprout out eventually and reflect back yet other seeds.

Thus the perception of a car as highly attractive and worth paying a stiff price for will repeat itself again and again and become habitual. Consequently, the energy stored in the alaya will take on a certain quality or is ‘perfumed’ by one’s actions, while the resulting seeds will sooner or later sprout out, spending their karmic effect.

An oft-used metaphor involves the ripples in a pond into which a stone is thrown. But whereas the ripples will soon have petered out, leaving the pond in its initial calm, karmic effects may last a very long time even if they are not noticed, like the threads of an Eastern rug that surface only here and there but together make up its pattern.

Karmic law of consequences

It must be kept in mind that karmic effects result from intention, that is, each and every intention regardless of whether it is bad or good. A well-intended desire to help someone get through a difficult patch will just as much add an impulse or seed to the store as an ill-intended scheme.

As everyone knows from their own experience, every action tends to strengthen the pattern of mental and physical activity that has already been set. Karmic consequences may be thought of as enhancing the existing pattern of habits and inclinations. Every time one finds oneself in the same situation one tends to repeat the particular action that has been carried out so often already under similar conditions, entrenching the well-worn habits yet deeper.

Karma may be understood as the law of consequences of good and evil deeds: doing good will bear good results, while doing wrong will have unpleasant consequences. Many actions however, are neutral; they do not produce karma because they were not intended but were simply responses to prevailing situations like watering a drooping plant or saying good morning on entering the office. Such actions, which abound in everyday life carry no karmic consequences ― only intentional actions do. Much of this has already been treated in the second chapter but much of what follows has not.

Karmic consequences stretch over more than one life

Karma has just been called a law but in contradistinction to scientific laws it does not have a linear ‘if ― then’ or ‘cause ― effect’ nature. Whereas iron cannot but expand (effect) when heated (cause), karmic consequences may take a long time to occur and may even stretch over more than one life.

This is the reason why rebirth is the corollary of karma.

It is important to realise that in Buddhism rebirth does not involve an unchanging I or soul that transmigrates again and again. It rather pertains to the energy that according to the skandha formula constitutes our real nature. This energy assumes a new form when the old one has worn out and fallen apart.

Moreover, because at least two main karmic causes plus a number of auxiliary ones have to come into play and it is their combination that determines the result, karma does not operate in linear chains but in intricate patterns.

“[B]eing is nothing but a combination of physical and mental forces or energies. What we call death is the total non-functioning of the physical body. Do all these forces and energies stop altogether with the non-functioning of the body? Buddhism says ‘No’. Will, volition, desire, thirst to exist, to continue, to become more and more, is a tremendous force that … continues manifesting itself in another form, producing re-existence which is called rebirth”.[5]

In some respects the karma doctrine points to a similar direction as the Christian providence and the fate of the ancient Greeks except that there is no transcendent God or ‘first cause’ to mete out the consequences and, more importantly, it is not fateful. We are not helpless in the face of karma; we are conditioned but by no means determined by it. At every moment the situation we find ourselves in is the result of our karmic self-conditioning, allowing us to become better or worse by our own efforts. We are heir to our deeds.

Thus, a good pattern of karmic consequences may be enhanced by intentional good thoughts, speech, and actions, while a bad pattern may be ameliorated by them. In the same way, bad thoughts and so on may strengthen existing bad patterns or decrease good ones. But whatever we do, an

“external agency that rewards and punishes the good and evil deeds of man has no place in Buddhist thought”.[6]

It’s we who are the authors of our lives.

The Three Fires: desire, hatred and delusion

In the Buddhist view, the ‘mental realm’ comprises cognitive as well as emotional components. We know that the same holds for the Chinese heart-mind.

The prime example of emotional karma-productive action is desire, which is part of the formula of the Three Fires.

The other two fires are hatred and delusion, that is, the delusion of there being an independent I.

Thus, two of the three fires, desire and hatred refer to the basic movements of the heart-mind towards or away from something, or, put differently, to inclinations to one of two sides.

No-I points to the same direction as wuwei

Allowing for the diverging contexts, this would seem to entail that the Buddhist samskara aggregate, powered by the fires, points to what in the Confucian Mean was called ‘inclining to either side’, which, as argued earlier, also comprised the gist of what the Daoist busied himself to lose.

In other words, the Buddhist no-I points to the same direction as the wuwei of the Daoist practitioners, and the ‘don’t incline’ of the Mean.

And finally, taking into account that desiring or inclining to ‘this’ rather than ‘that’ is a perfect instance of what in Buddhism is called ‘I’ and hence suffering, all this would seem to add up as follows:

- because inclination/desire = I = suffering,

- then no-inclination/desire = no-I = no suffering.

Now, the first line may also be put as:

- if inclination/desire, then I; if I, then

It bears repeating that these terms do not form a causal series. Desire does not cause I, and the I does not cause suffering but desire is identical with I, and I is identical with suffering.

Twelve-linked Chain of Arising Due to Conditions

Moreover, the lines above would almost seem to form part of the Pratitya Samutpada, the Formula of the Twelve-linked Chain of Arising Due to Conditions. The formula teaches that nothing is independent and stands alone. Quite to the contrary, everything is conditioned and therefore inter-dependent and relative. The principle of conditionality explains the coming to be of I by twelve links, each of which is both conditioned and conditioning:

Through ignorance (delusion) (1) are conditioned volitional actions or karma-formations (2). Through volitional actions is conditioned consciousness (3). And so on: Consciousness mental and physical phenomena (4). Mental and physical phenomena à the six senses (5). Six senses à sensorial and mental contact (6) Contact à sensation (7). Sensation à desire (8). Desire à clinging (9). Clinging à becoming (10). Becoming à birth (11). Birth à old age and death (12).

The formula can also be reversed, rather like line 2 above. This line may also be put as ‘if no inclination/ desire, then no-I; if no-I, then no suffering’.

Indeed, stopping to incline/ desire brings the entire process of coming to be to a halt. Through the cessation of ignorance or delusion, volitional activities or karma-formations cease; through the cessation of volitional activities, consciousness ceases, and so on: … through the cessation of birth, old age and death cease.

To conclude, the Twelve-linked Chain covers past (links 1 and 2), present (links 3-10), and future (re)births (links 11 and 12). But, as mentioned above, these births do not refer to ‘my’ past and future lives because there is no abiding I that is reincarnated. What they do refer to, however, is the arising and cessation of momentary elements of consciousness (dharmas). This means, in other words, that the links of the chain apply to the arising and passing away of the present state of consciousness, and then the next, and the next, and so on into infinity.

At this point we should briefly return to the five skandhas because these must ultimately be seen along similar lines. That is, as heaps or aggregates of momentary elements that come together to give the appearance of physical forms, feelings/sensations, perceptions, mental/volitional formations, and sense consciousnesses.

One sees that the Twelve-linked Chain of Arising Due to Conditions applies to the consciousness of physical and mental formations that continuously arise and cease to be. In everyday life these formations seem to be real enough but in fact they are made up of momentary elements of consciousness that come and go according to the Twelve-linked Chain. The Chain itself, finally, keeps coming into existence fired by volitional intentions, that is, the I-willed karma-productive activities of body, speech, and heart-mind.

The Buddhist formulas all point to the ultimate reality of no-I

It is seen then, that the Buddhist formulas presented in this section, the Four Noble Truths, the Three Signs of Being, the Five Aggregates, the Three Fires, and the Twelve-linked Chain all point to the ultimate reality of no-I.

And one also sees the other side of the coin, namely that the formulas and key-concepts revolve around each other, mutually presupposing and supporting each other as it were, because they all derive their meaning from the network which they jointly make up and share ― standing alone and taken by themselves however, they are pointless and devoid of practical meaning.

- Ch’u, Ta-Kao. (Transl) (1937/1976) Tao te ching. London: Umwin.

- Chan, Wing-tsit. (1963). A sourcebook in Chinese philosophy. Princeton: Princeton U.P.

- Chang, Chung-yuan. (1975). Creativity and Taoism. London: Wildwood House.

- Chang, G.C.C. (1972). The Buddhist teaching of totality ― The philosophy of Hwa Yen Buddhism. London: Allen & Unwin.

- Cleary, Th. (1983) Entry into the inconceivable ― An introduction to Hua-Yen Buddhism. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

- Conze, E., Horner, I.B., Snellgrove, D., & Waley, (Transl). (1990). Buddhist texts through the ages. Boston: Shambala.

- Fairbank, J.K. & Goldman, M. (2006). China: A new history. Cambridge (MA): Harvard U.P.

- Fung, Yu-lan. (1937/1952). A history of Chinese philosophy, 2 Vols. (Transl Derek Bodde). Princeton: Princeton U.P.

- Fung, Yu-lan. (1960). A short history of Chinese philosophy. New York: Macmillan

- Hansen, C. (1989). Language in the heart-mind. In R.E. Allinson (Ed.).

- Jullien, F. (2000). Detour and access: Strategies of meaning in China and Greece (Sophie Hawkes, transl.). New York: Zone Books.

- Liu, Xiaogan (2003). Confucianism: Texts in Guodian bamboo slips. In A.S. Cua (Ed.). Encyclopedia of Chinese philosophy (pp. 149-153). New York: Routledge.

- Lloyd, G.E.R. & Sivin, N. (2002). The way and the word: Science and medicine in early China and Greece. New Haven: Yale U.P.

- McRae, J.R. (2003). Seeing through Zen: Encounter, transformation, and genealogy in Chinese Chan Buddhism. Berkeley: Univ. California Press.

- Piyadassi, M. (1991). The spectrum of Buddhism. Colombo: Karunaratne & Sons.

- Rahula, W. (1959). What the Buddha taught. New York: Grove Press.

- Schloegl, I. (1975). The wisdom of the Zen masters. London: Sheldon Press.

- Suzuki, D.T. (1962). The essentials of Zen Buddhism. London: Rider.

- Takakusu, J. (1947/1975)- The essentials of Buddhist philosophy. New Delhi: Oriental Books Reprint Corporation.

- Watson, (Transl). (1968). The complete works of Chuang Tzu. New York: Columbia U.P.

- Watson, (Transl). (2003). Zhuangzi ― Basic writings. New York: Columbia U.P.

- Williams, P. (1989). Mahayana Buddhism: The doctrinal foundations. London:

- Yampolsky, Ph.B. (Transl). (1967). The Platform sutra of the sixth patriarch. New York: Columbia U.P.

Notes

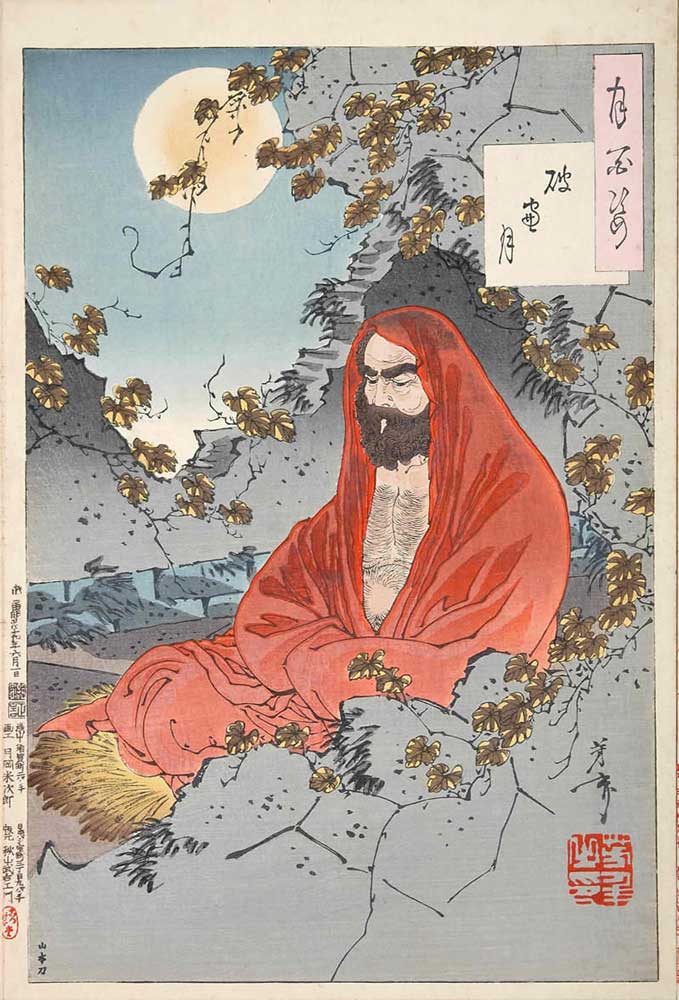

[1] Source in the Public Domain of a woodblock print (1887) of the Bodhidharma — by Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (1839–1892) “The moon through a crumbling window” – Series title One Hundred Aspects of the Moon.

[2] Fairbank & Goldman, 2006, p. 73

[3] Lloyd & Sivin, 2002, p. 238

[4] Takakusu, 1975, p. 32

[5] Rahula, 1959, p. 33

[6] Piyadassi, 1991, p. 184