Hans van Rappard

15 ― From: Rappard, H. van (2009). Walking Two Roads ― Accord and Separation In Chinese and Western Thought. Amsterdam: VU University Press. Chapter 5, pp. 161-164.

Enriched edition with illustrations and with the author’s permission.

part 1 – part 2 – part 3 – part 4 – part 5 – part 6 – part 7 – part 8 – part 9 – part 10 – part 11 – part 12 – part 13 – part 14 – part 15 – part 16 – part 17

Looking back at chapters four and five a striking similarity between the Chinese and the Hellenistic philosophical ways of life springs to mind.

In both cases philosophy constitutes a way of life rather than an abstract and theoretical affair. Related to this of course, is the fact that Daoists and Buddhists alike would have fully agreed with their Hellenistic colleagues that people are the slaves of their passions. But they proposed different explanations of this sorry phenomenon.

Whereas the Chinese traced it solely to the wrong attitude that people take towards things and events, the Epicureans ― but this hardly goes for the Stoics ― put it also down to the things and events themselves, or at least certain types of them.

‘Head work’ versus ‘body work’

Moreover, and probably related to this, the Hellenists and the Chinese thought along quite divergent lines with respect to the practice of self-cultivation. For present purposes the difference can be summarised simply as ‘head work’ versus ‘body work’ because, as markedly distinct from the Chinese ways their Hellenistic counterparts were cognitively and intentionally oriented.

And yet, and this constitutes an interesting problem, contrary to this fundamental difference, in both ancient Greece and China their divergent practices all came down to the cultivation of the present moment.

Conceivably however, the Stoic philosopher who was finally able to put his individual will wholly into a great Yes! to the will of universal reason (logos) was at that point just as fully in the present moment as his Chinese counterpart ― even if the Stoic called this a ‘thought’. After all, his frame of thinking would prevent him from naming it differently. However, it is difficult to understand the Epicurean ‘thought of pleasure’ along similar lines.

Thinking and being in the present moment

But then, one wonders, wouldn’t it be possible to ‘thinkingly’ be in the present moment? Couldn’t the cultivation of the ‘now’ be a matter of head work?

The short answer is No.

The somewhat longer answer begins by pointing out that thinking, or any other mental activity for that matter, needs an object. Regardless of whether it is approached from an Eastern or Western angle, to think is always to think-of-something, while to reject is to reject-something, just as wanting cannot but involve something-wanted.

William James[2] observed this too and said,

“thinking always appears to deal with objects independent of itself”

(italics added HvR).[3]

It follows that since thinking is about an object, that is, something other than itself it cannot but go beyond the present moment. In other words, thinking is post-hoc; it never is and never could be in the here & now ― and this, incidentally, is why the Stoic ‘thought’ seems to sit better with the present moment than the Epicurean ‘thought of pleasure’.

True enough, the actual thinking process takes place in the present and could not be anywhere else so to speak, but because it is directed at a goal (object) in the future ― however near or far away, or at a memory of something perceived or thought in the past ― thinking dwells perforce in the future or the past.

As the Epicureans understood, our hopes and fears cannot but concern the future. Just reflect: where are we when thinking? Are we with the activity of thinking? No, we are not and the reason is easy to see. After all, by virtue of ‘dealing with objects other than itself’ thinking cannot be ‘with itself’.

Thinking requires an object

Another way to put this is that thinking cannot think of itself any more than the eye can see itself; both are unable to function as their own objects. The meaning of vi in vijnana precludes this.

James also saw this and wrote,

“the Thought never is an object in its own hands”.[4]

An expression like ‘lost in thought’ demonstrates that language recognises that thinking cannot do without an object, and also that this object may take us ‘far from home’ or at least ‘out for lunch’. Thinking may, and usually does, carry us away though not as ruthlessly as the passions or appetites.

But strictly speaking ― that is, taking into account that thinking requires an object ― we are, when thinking, almost always lost in thought; indeed, lost because we are not aware that we are thinking.

Reflect again: where are we when we think? Are we with the act of thinking? Unlikely, though it may hold for some of us some of the time. Most of us, however, will most of the time dwell exactly there where their thoughts are ― somewhere in the future or the past but, be it wherever it may, it will not be the present moment.

Incapable of conceiving something ‘totally other’

The object-directed nature of mental activity has yet another consequence pertinent to the Chinese and Hellenistic ways of self-cultivation. Because, as detailed above, thinking cannot just think itself it is inherently incapable of conceiving something ‘totally other’, that is, something completely different from the objects available to it. By virtue of requiring an object, thought simply cannot conjure up a world that is well and truly different from reality as we have come to know it.

Let me elaborate by means of an example that broadly speaking may be familiar to many.

When I read stories and cartoons to my children one cartoon featured an astronaut who sailed through the universe in an incredibly advanced spaceship. Effortlessly star-hopping and using black holes as shortcuts to out of the way galaxies, in one particular story our hero arrived at a small planet in a remote universe. Now, what was the first thing he encountered? A medieval sailing ship orbiting the planet manned by a lone Flying Dutchman-like character. Moreover, on having landed he had to engage in many a swordfight against the cronies of unsavoury politicians and coup plotters, happily assisted by his bikini clad consort.

Granted, many science fiction stories are more developed but to the extent that I have sampled the literature the common Martian tends to sport somewhat greenish and distorted but nevertheless quite recognisable human features … Has the unbridled imagination of science fiction writers ever been able to depict worlds that are completely alien to us, lacking any relation or allusion to the world as we know it? It would be surprising if the worlds that they have thought up were really more out of the way and farther beyond understanding than, say, those described in the messages conveyed by your average occult medium.

Of course, the deceased may be happy in the beyond, enjoying seven star conveniences, indefatigably playing winged harps, pursuing heavenly maidens or whatever they fancy but theirs is still a well-recognisable human happiness. And how could this be different?

Thinking-objects can after all only be derived from the fourth aggregate, our perceptions and memories. Surely, creativity and imagination are great faculties but they cannot achieve the impossible: to devise worlds that are totally ‘other’, that is, totally out of touch with our world.

Warning against making images

This must be why so many religious and other ways of self-cultivation ― but not the cognitive Epicurean and Stoic pursuits ― forbid or at least warn against making images, material and mental. It is held to be impossible and hence utterly misleading to try and portray the ‘totally Other’ by means of thinking-objects that are perforce derived from the ‘totally this’, the human world.

A host of pertinent writers counsel to un-think or de-objectify mental activity and looking back at chapter four this should not surprise us one bit. After all, what is it that the Laozi advised to lose and lose and lose yet more of? What is it that the heart-mind is urged by the Zhuangzi to abstain from while it fasts? It is the incessant object directedness or seeking of our heart-minds.

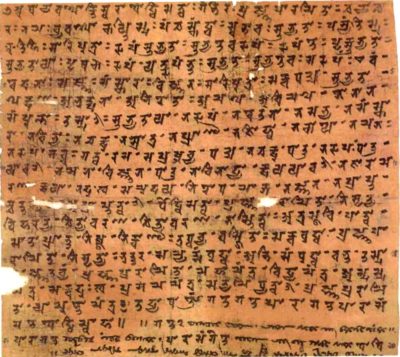

And this is no different in Buddhism. As the Heart Sutra says,

“No forms, sounds, smells, tastes, touchables, or objects of mind”.[7]

- Bett, R. (2006). Stoic ethics. In M.L. Gill & P. Pellegrin (Eds.). A companion to ancient philosophy (pp. 530-548). Oxford: Blackwell.

- Green, C.D. & Groff, P.R. (2003). Early psychological thought: Ancient accounts of mind and soul. Westport (CT): Praeger.

- Hadot, P. (1995). Philosophy as a way of life ― Spiritual exercises from Socrates to Foucault. (A.I. Davidson, ed.; Chase, Transl). Oxford: Blackwell.

- Hadot, P. (2002). What is ancient philosophy? (M. Chase, Transl). Cambridge (MA): Harvard U.P.

- James, W. (1890/1950). The principles of psychology, Vol. I. New York. Dover Publ.

- Long, A.A & Sedley, D.N. (1987). The Hellenistic philosophers, Vol. I. Cambridge: Cambridge U.P.

- Nussbaum, M.C. (1994). The therapy of desire: Theory and practice in Hellenistic ethics. Princeton: Princeton U.P.

- Staniforth, M. (Transl). (2004). Marcus Aurelius: Meditations. London: Penguin Books.

Notes

[1] Source in the Public Domain of Confucius, Laozi and Buddhist Arhat by Ding Yunpeng. Hanging scroll, ink and colour on paper. Painting is located in the Palace Museum, Beijing.

[2] Lees meer over William James

[3] James, 1890/1950, Vol. I, p. 225

[4] James, 1890/1950, Vol. I, p. 340

[5] Source in the Public Domain of a Fresco (1511) The School of Athens – by Raphael 1483–1520) Raffaello Sanzio

Collection Apostolic Palace – Pinacoteca Ambrosiana – Vatican Museums.

[6] Source in the Public Domain of Sanskrit manuscript of the Heart Sūtra, written in the Siddhaṃ script. Bibliothèque nationale de France.

[7] Conze, 1988, p. 111