Hans van Rappard

14 ― From: Rappard, H. van (2009). Walking Two Roads ― Accord and Separation In Chinese and Western Thought. Amsterdam: VU University Press. Chapter 5, pp. 149-161.

Enriched edition with illustrations and with the author’s permission.

part 1 – part 2 – part 3 – part 4 – part 5 – part 6 – part 7 – part 8 – part 9 – part 10 – part 11 – part 12 – part 13 – part 14 – part 15 – part 16 – part 17

Epicureanism was founded by the Athenian Epicurus (341-270 BCE). Since he taught in the garden attached to his house his teaching was often called, the philosophy of the garden.

The school never became very popular in Rome but, as was the case with Stoicism, most information on Epicureanism came from Roman sources such as Cicero, who, decrying its tenets, quoted large parts of Epicurus’ works.

An important writing is Lucretius’ (ca 100-ca 55 BCE) On the nature of the universe, which contains much material on Epicurean physics. There seems to have been an Epicurean community in Pompeii at the time of the eruption of Mount Vesuvius and many of the texts that survive were recovered from its library.

Hedonism and ‘pleasure’ as key-notion

The name Epicureanism is likely to have more or less hedonistic overtones and indeed, ‘pleasure’ is the key-notion of their doctrines. But nevertheless, the school is not nearly so hedonistic as is often thought. As Epicures wrote,

“So when we say that pleasure is the end [we mean]freedom from pain in the body and from disturbance of the soul. For what produces the pleasant life is not continuous drinking and parties or pederasty or womanizing or the enjoyment of fish and the other dishes of an expensive table, but sober reasoning which tracks down the causes of every choice and avoidance, and which banishes the opinions that beset souls with the greatest confusion”.[2]

Avoiding suffering and fear

For the Epicureans just as much as for the Stoics, philosophy is basically therapy. Our lives must be healed ― but of what ailment? As Epicures saw it, the unhappiness that pervades the lives of human beings can be explained by the fact that they are afraid of things which are not to be feared, while they desire things that need not be desired and are beyond their control. Consequently, their lives are consumed in worries over unjustified fears and unsatisfied desires, thus depriving themselves of the only genuine pleasure there is to be had: the simple pleasure of being alive. For the Epicurean therefore, pleasure comes down to the suppression of suffering. We try to avoid suffering and fear but,

“When once we have succeeded in this, the tempest of the soul is entirely dissipated, for the living being now no longer needs to move forward anything as if he lacked it, or to seek something else by which the good of the soul and body might be achieved. For we have need of pleasure precisely when we are suffering from the absence of pleasure. When we are not suffering from this lack, we do not need pleasure”.[3]

Epicurean healing is a matter of bringing the mind back from the worries and difficulties of life to the sheer joy of existing. As mentioned earlier, Epicureanism had also designed a physics to help liberate people from fear, which in their case was accomplished by, among other things, demonstrating that the gods cannot influence the course of the world and that death, being complete dissolution, actually does not form part of life.[4]

“Accustom yourself to the belief that death is nothing to us. For all good and evil lie in sensation. Hence a correct understanding that death is nothing to us makes the mortality of life enjoyable, not by adding infinite time, but by ridding us of the desire for immortality. For there is nothing fearful in living for one who genuinely grasps that there is nothing fearful in not living … Therefore the most frightful of evils, death, is nothing to us, seeing that when we exist death is not present, and when death is present we do not exist”.[5]

The main source of their unhappiness, insatiable desires

Having thus disposed of two major worries, Epicureanism set out to deliver human beings from what in everyday life is the main source of their unhappiness, insatiable desires, by distinguishing between

- desires that are natural as well as necessary,

- desires that are natural but not necessary, and

- desires that are neither natural nor necessary.

In order to bring about freedom from worries and so clear the mind for the unalloyed pleasure of existing it is enough, according to the Epicurean philosophers, to satisfy the first category of desires and to completely forsake the third one, while the desires of the second category are assumed to also be given up eventually.

The difference with hedonism comes particularly to the fore in the Epicurean sense of piety and gratitude towards all things.

“Thanks to blessed Nature”,

Epicurus taught,

“that she has made what is necessary easy to obtain, and what is not easy unnecessary.”[6]

Epicurean meditation

Again like the Stoics, the Epicureans are assumed to meditate day and night on brief formulas or summaries in order to keep their principles near at hand. One of these, a fourfold healing formula (tetrapharmakos) says,

“God presents no fears, death no worries. And while good is readily obtainable, evil is readily endurable”.[7]

Collections of Epicurean aphorisms have existed in abundance, meeting an apparently high demand. And again just as in Stoicism, the study of the philosophical treatises of the school’s founders and great followers was also used as an exercise designed to provide grist to the meditative mills.

Study of physics

Particularly important in Epicureanism was the study of physics, which, as we have seen, was not unfamiliar to the Stoics either. Crucial aspects were the contemplation of the physical world and the imagination of the infinite void.[8] These exercises were assumed to bring about a drastic change of one’s way of looking at the world. With regard to the former an Epicurean saying admonished,

“Remember that, although born mortal and having received a limited life, you have nevertheless risen, through the science of nature, up to eternity, and that you have seen the infinity of things: those that shall be and those that have been”.[9]

The imagination of the infinite may provide the philosopher with the pleasure of an expansion of the self, a plunging into the infinite universe, which is described as an infinite dilation of the closed universe and also, taking the opposite perspective as it were, as a stretching of the mind into immensity. Lucretius has described this as,

“the walls of the world open out, I see action going on throughout the whole void … Thereupon from all these things a sort of divine delight gets hold upon me and a shuddering, because nature thus by [Epicurus’] power has been so manifestly laid open and unveiled in every part”.[10]

The need to relax the mind

Next to meditation the Epicurean school used other spiritual exercises. Much in contradistinction to the Stoics they recognised the need to relax the mind. Rather than preparing oneself to all sorts of conceivable misfortunes, they preferred to detach themselves from the images of unpleasant events and fix the mind on the joyful ones instead. We are advised to relive memories of past pleasures and to enjoy those of the present.

Surely, this is quite a distinctive spiritual exercise, Hadot observes, very different from the constant vigilance of the Stoics who were ever ready to safeguard their moral liberty. Epicureanism advocated a deliberate relaxation and serenity, along with deep gratitude toward nature for incessantly offering joy and pleasure, if only one knows how to find them.

Community life and friendship

The Epicurean was not expected to practise in quiet solitude. He was to live in a community of philosophers where friendship was considered the prime way toward self-cultivation and frequent examination of one’s consciousness, confession, and fraternal correction were deemed essential means.

Although teachers and disciples helped one another Epicurus himself seems to have assumed the role of a fairly authoritarian director of consciousness. ‘Act as though Epicurus were watching you’, was the adage and his students kept well in mind to ‘obey Epicurus, whose way of life we have chosen’. To them, the Master appeared ‘like a god among men’. Nevertheless, friendship was highly esteemed.

Cicero, who was not friendly disposed towards the Epicurean school could not help observing that

“Epicurus says that of all the things which wisdom provides in order for us to live happily, there is nothing better, more fruitful, or more pleasant than friendship. [In his own] little house, what a troop of friends there was … What a conspiracy of love united their feelings”.[11]

If for the Epicureans pleasure was a spiritual exercise, friendship also had its exercises. Hadot calls friendship even

“the spiritual exercise par excellence … The main goal was to be happy, and mutual affection and the confidence with which they relied upon each other contributed more than anything else to this happiness”.[12]

Differences in similar exercises

There is one more similarity between the two Hellenistic philosophies reviewed here. Just as Stoicism, its Epicurean counterpart knew the exercise of living in the present moment. However, in spite of the similar names the exercises are tellingly different in both schools and so this Epicurean exercise also warrants a good deal of attention.

Cultivating the present moment

It would be wrong to think that it were only the philosophers who paid special attention to the present moment; during the Hellenistic period the common Greek was brought up with a similar attitude.

Popular and philosophic views

Popular wisdom admonished people to be content with the present and to use it well. The first part of this advise meant being content with one’s earthly existence, while the second part, knowing how to use the present instant, meant that one was to know how to seize kairos, the decisive moment rich with opportunities, like a good general who knew exactly when to attack.

But for philosophers, living in the present moment was not just an attitude dictated by the culture they found themselves living in but an exercise that they went to great lengths to train. And in one way or another this held for all schools. According to Hadot the attention to the present is the key to all spiritual exercises. According to the Stoics, this vigilance freed them from the passions, which are after all caused by the past or the future and thus cannot be said to depend on us. Recall that this was an essential point in their philosophy. Concentration was encouraged on

“the minuscule present moment, which, in its exiguity, is always bearable and controllable”.[14]

Moreover, as will be seen below, such concentration also allowed the philosopher to attain to cosmic consciousness by making him attentive to the infinite value of each and every moment and accept it from the perspective of the universal law of the cosmos.

“[Both schools] privilege the present to the detriment of the past and above all of the future. They posit as an axiom that happiness can only be found in the present, that one instant of happiness is equivalent to an eternity of happiness, and that happiness can and must be found immediately, here and now. Both Epicureanism and Stoicism invite us to resituate the present within the perspective of the cosmos, and to accord infinite value to the slightest moment of existence”.[15]

Stoic view

We will turn to the Stoics first. We are familiar with their requirement that attention be paid to every instant of our life. It seems that the Stoic ‘now’ roughly came down to a moment of experience, which becomes a thing of the past as soon as one begins to reflect on it.

In the Stoic view, the present moment is sufficient for the happiness of the philosopher because it is only this that really belongs to him and that can be said to depend on him. This refers to the distinction between freedom and nature.

Many other thinkers have echoed this view ― which is not difficult to get clear on oneself ― that the past does not depend on me because it has now been fixated, while the future does not depend on me because it is not yet there and hence, that it is only the present that can be said to depend on me and thus truly is my own. Stated differently, neither the past nor the future ‘depend’ on me because both fall squarely outside the domain of my will, and it is only there that moral freedom is to be found; for the same reason good and evil too can only exist in the present. This is important.

Notion of the (free) will

What is found here is a first stirring of the notion of the will. In chapter three we have learned that this faculty occupied an important position in Augustine and his conception of it was partially anticipated by the Stoics. Now, if something depends on my will, I am accountable for it; if not, it does not depend on me and thus can be indifferent to me.

In the Stoic view past and future do not depend on human beings and so cannot be categorised as good or bad. It is therefore sheer waste of time ― a Stoic philosopher would counsel ― to worry about things and events of the past, and the same goes of course for the future. Yet, most of us do worry. But then, we are no Stoics. If we were, we would have learned to ‘delimit the present’.

“Do away with all fancies”,

Marcus Aurelius wrote,

“Cease to be passion’s puppet. Limit time to the present”.[16]

Only the present is our happiness

To the Stoics, only the present is our happiness and this is so for two reasons.

Firstly, because happiness is complete at every instant and does not increase over time. To be happy, is just to be happy; nothing can be added to it or subtracted from it and neither could my happiness be usefully compared with yours.

But what is it that gives the present moment such particular value? The answer is: death! The philosophers were counselled to carry out each action of their lives as if it were the last.[17]

Stoic happiness is an urgent matter. Since past and future are to no avail and death may strike at any moment it is, literally, now or never. Actually, it is here that the secret is found of the concentration on the present moment because,

“we are to give it all its seriousness, value, and splendour; in order to show up the vanity of all that we pursue with so much worry: all of which, in the end, will be taken away from us by death. Hence, each day must be lived with a consciousness so acute, and an attention so intense, that we can say to ourselves each evening: ‘I have lived; I have actualized my life, and have had all that I could expect from life’. In the words of Seneca: ‘He has peace of mind who has lived his entire life every day’”.[18]

The second reason why happiness can only be found in the present is that in it we possess the whole of reality and again nothing can be added to this ― not even infinite duration could give us more than we have right ‘now’.

“Were you to live three thousand years, or even thirty thousand, remember that the sole life which a man can lose is that which he is living at the moment; and furthermore, that he can have no other life except the one he loses. This means that the longest life and the shortest amount to the same thing. For the passing minute is every man’s equal possession, but what has once gone by is not ours. Our loss, therefore, is limited to that one fleeting instant… when the longest- and the shortest-lived of us come to die, their loss is precisely equal. For the sole thing of which any man can be deprived is the present; since this is all he owns, and nobody can lose what is not his”.[19]

Happiness is always perfect and complete in itself

In view of what the Chinese sages had to say on the topic it is worthy of note that for their Stoic counterparts happiness is always perfect and complete in itself ― it lacks nothing. The same holds for kairos[20], the opportune moment. This too, is a moment whose perfection does not depend on its quantity or duration but on its quality. Incidentally, this also explains why nothing can be added to the ‘now’; more and less, addition and subtraction are quantitative notions.

We can of course add a certain amount of time to a another amount of time, a couple of minutes to a quarter of an hour, but it is impossible to add ‘a couple of instants’ to the present moment. Kairos is only dependent on its quality and also ― and this is of particular interest in view of what the Chinese did say ― on the harmony which exists between one’s exterior situation and the possibilities that one has. Happiness is nothing more, nor less, than that instant in which man is wholly in accord with nature”.[21]

Living in harmony with universal reason: logos

What is required, then, is the immediate transformation of the Stoic’s way of thinking, of acting, and of accepting events. His nous must be in harmony with the logos, that is, he must think in harmony with truth, act in harmony with justice, and fully accept what life metes out. It is particularly important to whole-heartedly accept the conjunctions of causes and effects produced by the cosmic logos.

At each and every moment the Stoic must place himself within this universal perspective in order for his consciousness to become a cosmic consciousness. Living in harmony with universal reason, in other words, makes one’s consciousness expand into the infinity of the cosmos so that the entire universe is present to him.

Comparison with Eastern thinking

Given the central tenet of the Huayan school of Chinese Buddhism, Hadot’s explanation is of particular interest. For the Stoics cosmic presence is possible, he says,

“because there is a total mixture and mutual implication of everything with everything else. Chrysippus, for example, spoke of a drop of wine being mixed with the whole of the sea, and spreading to the entire world”.[23]

And as Marcus Aurelius wrote in his private notes,

“To see the things of the present moment is to see all that is now, all that has been since time began, and all that shall be unto the world’s end; for all things are of one kind and one form”.[24]

He also wrote, and this could almost be repeated by many Eastern teachers,

“Whatever may happen to you was prepared for you in advance from the beginning of time. In the woven tapestry of causation, the thread of your being had been intertwined from all time with that particular incident”.[25]

Indeed, Hadot concludes, one could speak here of a mystical dimension of Stoicism. At each and every moment the philosopher must say a resounding ‘Yes’ to the cosmos, that is, to the will of universal reason (logos). The all-important matter is to harmonise one’s own puny will with that of the universe ― that is, the present instant, exactly as it is. In Stoicism a profound feeling of participation may be found, a feeling of belonging to an all-embracing whole which transcends the confinement of our individuality, a feeling even of intimacy with the cosmos.

Epicurian view

In Epicureanism, no less than in Stoicism, a transformation of one’s life is sought and here too, a change of one’s attitude towards time is the crucial point.

Attitude towards time

The common people, the non-philosophers are continuously plagued by empty desires for wealth, power, and the rest but these are by their very nature impossible to satisfy in the present moment.

Actually, one does not have to be an Epicurean to see that our hopes and fears cannot but concern the future. Therefore, the philosopher is counselled to fully enjoy the pleasure of the present. If the past was unpleasant, just don’t think about it, and if the future arouses fear or intemperate expectations, don’t think about it either.

“Only thoughts about what is pleasant ― of pleasure, whether past or future ― are to be allowed into the present moment”.[26]

In view of our treatment of the Chinese way of life it must be noted that just as in Stoicism, in Epicureanism the present appears to be a particular kind of thought, ‘thoughts of pleasure’. Actually, much of what was learned about the Stoic conception of the present moment may also be found in the Epicurean view of pleasure. Just as according to the former school it was not possible to add to the present moment, the latter held that the quality of pleasure does not depend on the quantity of the desires that it satisfies.

The most intense pleasure is that which is least alloyed with worries and the most reliable to ensure peace of mind. This is particularly true with concern to the natural and necessary desires, essential for the preservation of life because, as the Epicureans felt, these are easy to satisfy without having to rely on the future and without getting exposed to the worries and uncertainties of a lengthy pursuit.

Recall that Epicurus said,

“Thanks be to blessed nature, who made necessary things easy to obtain, and things which are hard to obtain unnecessary”.

Not only is pleasure independent of the quantity of satisfied desires but ― and this also echoes the Stoics ― it does not depend on duration either. The Epicureans conceived of pleasure as perfect in itself and hence not fitting within the category of time. Pleasure is complete at any moment and prolongation could add nothing to it. Thus, pleasure is wholly in the present and it is useless to expect anything from the future. All that is needed is to limit one’s desires in a reasonable way, that is, to limit desires to those that are natural and necessary.

Pleasure is only to be found here and now, and this makes it an urgent matter. If pleasure can only be found in the present, how could you,

“who are not master of tomorrow … keep on putting off your joy?”,

Epicurus wonders,

“Yet life is vainly consumed in these delays, and each of us dies without ever having known peace”.

Carpe diem

Horace’s famous adage carpe diem[28], which forms part of his saying

“Life ebbs as I speak, so seize each day, and grant the next no credit”,[29]

must be read in the same light. Hence, to seize the day is no hedonist advise, rather, it is an invitation to realise the vanity and emptiness of our desires on the one hand, as well as the imminence of death, and the uniqueness of the present moment on the other. To the philosopher who does fully seize each day, every moment is a gift that fills him with gratitude.

“Believe that each new day that dawns will be the last for you: Then each unexpected hour shall come to you as a delightful gift”.[30]

But there is more to this because not only is the Epicurean to live each day, each moment even, as if it were his last but also as if it were his first. In other words, ‘Epicurean mind, beginner’s mind’.

Epicurean mind, beginner’s mind

Grateful wonder may be experienced when the philosopher accepts the present instant as completely new and unexpected. In this school, the secret of joy and serenity is found in the experience of the infinite pleasure that may come from the consciousness of one’s existence ― be it only for an instant.

Given their cosmic perspective this means that the Epicurean philosopher, not unlike his Stoic colleague,

“perceives the totality of the cosmos within his consciousness of the fact of existing”,

as Hadot puts it.

“Nature gives him everything within an instant”,

he continues and quotes Lucretius who wrote,

“You must always expect the same things, even though the span of your life should triumph over all the ages; nay, even were you never to die”.

In order to always keep in mind that one single instant may bring an experience of pleasure that knows no bounds, each day the Epicurean reflected

“I have had all the pleasure I could have expected”,

or, as expressed by Horace,

“He will be the master of himself and live joyfully who can say, every day: ‘I have lived’”.[31]

However, instead of taking Horace’s words as ‘I have lived’, they may also be understood as ‘I have lived’, that is, my life is over, and thus as referring to the Epicurean awareness of the imminence of death.[32]

Awareness of life’s finiteness

Actually, one of their exercises consisted of saying to oneself, ‘Today will be the last day of my life’. In a sense then, the acute awareness of life’s finiteness, necessary to free the philosopher from the worries and fears of everyday life, is the counterpart of the infinite pleasure of one’s being here this very moment ― this ‘now’, which, however, comprises all.

But then, what exactly is finiteness, and what is infinity here? Present moment, pleasure, finiteness, infinity ― all seem to revolve around each other. But what they ultimately come down to is the sheer wonder of the present moment: at once finite in its immediacy, and infinite in its fullness.

The treatment of Stoicism and Epicureanism has been focused on the practical side of their thinking, on their philosophies as ways of life, that is. Doctrinal differences have been largely left out of view; the picture as it has emerged is sufficiently detailed for present purposes.

Similarities between Stoicism and Epicureanism

In the course of our review we have come across a number of similarities, some fairly incidental, others rather important.

Undoubtedly, by far the most salient similarity concerns the fact that both Stoicism and Epicureanism privilege the here & now; both maintain that real contentment can only be realised in the present and that a single moment of it equals eternity. Hence, the slightest moment of one’s life has infinite value.[33]

Also, both schools counsel their philosophers to place the present within the perspective of the cosmos.

Moreover, and this is important in comparison to the Chinese ways of life, in Stoicism as well as Epicureanism the present is a thought ― their ‘now’ in other words is cognitive.[34]

Apart from these similarities, Hadot observes that with respect to their basic attitudes the two schools correspond to

“two opposite but inseparable poles of our inner life: tension and relaxation, duty and serenity, moral conscience and the joy of existence”.[35]

I would think however, that this difference is more than upset by their mutual emphasis on the cultivation of the present moment.

Self-transformation and the free will

Actually, all Hellenistic schools[36], not just the two that have been examined, agreed that human beings can transform themselves. After all, that is what the spiritual exercises are all about: self-transformation, which enables one to live in conformity with one’s true nature or reason, rather than prejudices and social conventions.

And all schools believed in the freedom of the human will by virtue of which man may better and ultimately realise himself.

“One conception was common to all the philosophical schools: people are unhappy because they are the slaves of their passions. In other words, they are unhappy because they desire things they may not be able to obtain, since they are exterior, alien, and superfluous to them. It follows that happiness consists in independence, freedom, and autonomy. In other words happiness is the return to the essential: that which is truly ‘ourselves’, and which depends on us … all spiritual exercises are, fundamentally, a return to the self…. The ‘self liberated in this way is no longer merely our egoistic, passionate individuality: it is our moral person, open to universality and objectivity, and participating in universal nature or thought”.[37]

Conclusion

The Stoic and Epicurean philosophers were to transform themselves into fully reasonable beings. To the extent that they succeeded in this, they would be able to harmonise their will with the will of the reason-animated cosmos. Clearly, reason is the crucial characteristic of both the philosopher’s nous and the logos of the universe.

But in spite of the stress on the harmony between man and nature and the feeling of participation that may ensue from it, the philosopher’s individual will seems to remain fully operative, as is suggested by the words independence and autonomy. To put this in a different way, it would seem that the transformed philosopher, even if he has laid his egoistic dispositions to rest, has not really put a stop to the activity of will and intention. Fitting in with this is the fact that the present moment assumes the form of a thought, that is, it is a matter of cognition.

Self-cultivation in East and West

All this sits well with the Western way of thinking as we saw it emerge in ancient Greece, but not quite so well with what was learned about the Chinese practises of self-cultivation. From that perspective, Hellenistic self-transformation would probably appear to be a rather ‘heady’ affair.

At least since the early days of Hellenism at the end of the fourth century BCE the Greeks have been in touch with Central Asia. Since at that time the Mean (Zhongyong), was still hidden in the Li Ji as it were, it is not likely ― and to the best of my knowledge has indeed never happened ― that a Stoic philosopher got hold of a translation of it. Conceivably however, this might have happened.

It was not only loot that Alexander’s armies carried back home nor was it only silk that was transported along the Silk Road. Now, assuming for the sake of argument that a Stoic did actually read what is now called the Mean, he might have felt inspired to adapt its first lines to his own philosophy. Imagine the fascination and ensuing academic quarrels on finding an ancient manuscript beginning with the following lines:

What the cosmos confers on man is called reason,

The exercise of reason constitutes the way towards transformation,

Practising the way towards transformation is called philosophy.

Hadot briefly refers to a couple of authors according to whom the ancient Greeks were closer to the East than we are.[38]

The conclusion of this chapter would seem to point in the same direction.

- Bett, R. (2006). Stoic ethics. In M.L. Gill & P. Pellegrin (Eds.). A companion to ancient philosophy (pp. 530-548). Oxford: Blackwell.

- Green, C.D. & Groff, P.R. (2003). Early psychological thought: Ancient accounts of mind and soul. Westport (CT): Praeger.

- Hadot, P. (1995). Philosophy as a way of life ― Spiritual exercises from Socrates to Foucault. (A.I. Davidson, ed.; Chase, Transl). Oxford: Blackwell.

- Hadot, P. (2002). What is ancient philosophy? (M. Chase, Transl). Cambridge (MA): Harvard U.P.

- James, W. (1890/1950). The principles of psychology, Vol. I. New York. Dover Publ.

- Long, A.A & Sedley, D.N. (1987). The Hellenistic philosophers, Vol. I. Cambridge: Cambridge U.P.

- Nussbaum, M.C. (1994). The therapy of desire: Theory and practice in Hellenistic ethics. Princeton: Princeton U.P.

- Staniforth, M. (Transl). (2004). Marcus Aurelius: Meditations. London: Penguin Books.

Notes

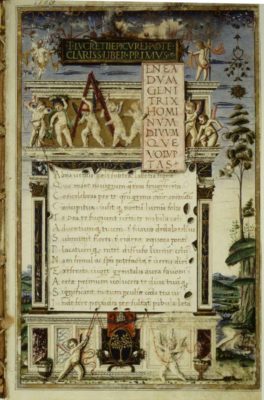

[1] Source in the Public Domain of a manuscript from 1483 of De rerum natura – Lucretius – This elegant manuscript of Lucretius’s philosophical poem, copied by an Augustinian friar for a pope, is an example of the interest in ancient accounts of nature taken by the Renaissance curia. The work, written in the first century B.C., contains one of the principal accounts of ancient atomism. The poem was little known in the Middle Ages and its author dismissed as an atheist and lunatic, but after the discovery of an early manuscript in 1417 by the humanist and papal secretary Poggio Bracciolini, it circulated widely in Italy. This is one of numerous copies made at that time. The coat of arms of Sixtus IV appears on this page. Vat. lat. 1569 fol. 1 recto medbio04 NAN.13

Source https://www.ibiblio.org/expo/vatican.exhibit/exhibit/f-medicine_bio/Medicine_bio.html

Author In Latin, Copied by Girolamo di Matteo de Tauris for Sixtus IV, Italy, 1483.

[2] Long & Sedley, 1987, p. 114

[3] Hadot, 2002, p. 116

[4] Read more on the ‘Classical Art of Living

[5] Long & Sedley, 1987, pp. 149-150

[6] Hadot, 1995, p. 87

[7] Hadot, 1995, p. 87

[8] Read more on Emptiness

[9] Hadot, 2002, p. 204

[10] Hadot, 1995, p. 88

[11] Hadot, 2002, p. 125

[12] Hadot, 1995, p. 89

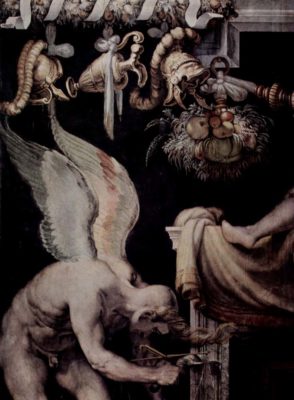

[13] Source in the Public Domain of a fresco if Kairos (circa 1553) in Palazzo Sacchetti collectie Rome. Source: The Yorck Project (2002) 10.000 Meisterwerke der Malerei (DVD-ROM), distributed by DIRECTMEDIA Publishing GmbH. ISBN: 3936122202.

[14] Hadot, 1995, p. 85

[15] Hadot, 1995, p. 222

[16] Staniforth, 2004, p. 81

[17] Read more on the spiritual meaning of death

[18] Hadot, 1995, p. 229

[19] Staniforth, 2004, pp. 16-17

[20] Read more about Kairos

[21] Hadot, 1995, p. 228

[22] Source in the Public Domain: Final moments in the life of Chrysippus. Engraving from 1606 by Giuseppe Porta (1520–1575) “Engraving of the final moments of the life of the Stoic philosopher Chrysippus, who reportedly died laughing while watching a donkey eat figs. From the 1606 Italian book Delle Vite de Filosofi di Diogene Laertio Libri X. Image appears on page 48 and on page 55. The woodcuts in the book are attributed to “Gioseffo Salviati”. Probably Giuseppe Porta, whose woodcuts of philosophers first appeared in a 1540 book called Le ingeniose sorti, composte per Francesco Marcolini da Forli. Source/Photographer https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=nuQMrNwvJPYC

[23] Hadot, 1995, p. 229

[24] Staniforth, 2004, p. 68

[25] Staniforth, 2004, p. 123

[26] Hadot, 1995, p. 223

[27] Source in the Public Domain of the First-century CE Roman fresco from Pompeii, showing The mythical human sacrifice of Iphigenia, daughter of Agamemnon. Epicurus’s follower, Lucretius, cited this myth as an example of the evils of popular religion, in contrast to the more wholesome theology advocated by Epicurus. “Iphigeneia carried to the sacrifice (centre) while the seer Calchas (on the right) watches on and Agamemnon (on the left) covers his head in sign of deploration. In the sky, Artemis appears with a hind which will be substituted to the young girl.”

Collection Naples National Archaeological Museum.

[28] Read moe about Carpe diem

[29] Hadot, 1995, p. 224

[30] Hadot, 1995, p. 225

[31] Hadot, 1995, pp. 225

[32] Hadot, 1995, pp. 225-226

[33] Read more on Meditations of Aurelius

[34] Nussbaum, 1994, pp. 111, 335

[35] Hadot, 1995, p. 108

[36] Read more about Hellenistic schools

[37] Hadot, 1995, pp. 102-103

[38] Hadot, 2002, pp. 278-279