Hans van Rappard

11 ― From: Rappard, H. van (2009). Walking Two Roads ― Accord and Separation In Chinese and Western Thought. Amsterdam: VU University Press. pp. 125-135.

Enriched edition with illustrations and with the author’s permission.

part 1 – part 2 – part 3 – part 4 – part 5 – part 6 – part 7 – part 8 – part 9 – part 10 – part 11 – part 12 – part 13 – part 14 – part 15 – part 16 – part 17

Huayan

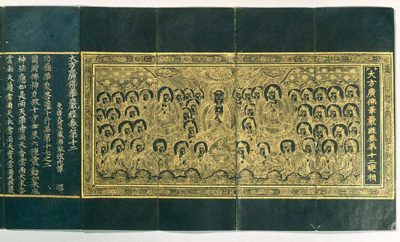

Avatamsaka sutra, Huayan or Flower Garland

Like the other Buddhist schools developed in China except for Chan the Huayan school was based on one particular sutra, the Avatamsaka sutra. Its Chinese name is Huayan or Flower Garland.

Translated in the fifth century, it was systematised by the third patriarch, Fazang (643-712). Because of its subtlety the Huayan school is often called the philosophical apex of Chinese Buddhism. It is also characteristically Chinese, which comes to the fore in its views on the relation between shi, variously rendered as objects, phenomena, form, or appearance, and li, principle, or reality.

In line with Mahayana Buddhism at large, Huayan holds that the phenomena, the things and events in the world that are perceived by the senses are interdependent or empty. This is so because, being conditioned by other phenomena they lack independent or intrinsic self-natures. There is nothing in them that really stands on its own as it were, no really independent or absolute core.

As Fazang said,

“Observe that all things are born from causes and conditions, and so have no individual reality, and hence are ultimately empty”.[2]

In the breath-taking vistas conveyed by the Huayan sutra all phenomena are fully dependent on and related to each other.

Put thus however, the message of the Huayan school[3] might seem to be no more than a pretty straightforward Buddhism and there would be little reason to call it a philosophical apex. But this qualification is easier to understand once it is understood that the sutra does not depict the world as seen by ordinary mortals but by a Buddha and that from such a perspective all phenomena in the universe interpenetrate.

The Huayan is particularly famous for just this theme.

As seen by a Buddha, the world

“is one of infinite interpenetration. Inside everything is everything else. And yet all things are not confused”.[4]

A candle and a Buddha statue placed surrounded by mirrors

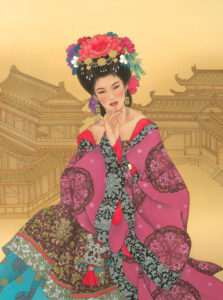

Such a perspective is difficult to appreciate and it is not surprising that Fazang, who had easy access to the court, found himself faced with an exasperated empress Wu (627-705)[5] when he tried to explain the intricacies of the Huayan. But he was a good teacher with a characteristically Chinese knack of bringing highly abstract topics down to earth.

Recognising the difficulties experienced by the empress, Fazang had a candle and a Buddha statue placed surrounded by mirrors. When the candle was lit, the statue was reflected in every mirror, while each of these reflections were reflected in all the other mirrors so that in any one mirror were the reflections of all the others.

The background of this artful didactic device is found in the Huayan doctrine of Indra’s net, which would be less easy to replicate in one’s bathroom and considerably more expensive because it concerns a net of jewels. In Indra’s net each jewel reflects all the other jewels but the reflections of all the jewels in each individual jewel also contain the reflections of all the other jewels, ad infinitum. This illustrates the interpenetration of all things.

We are used to taking things purely at face value; a chair is a chair and that is all there is to it. We do not realise that it has been produced and that for this to happen trees have been cut, wood has been worked and other materials and energy have been used and that once manufactured, it has been transported to the shop where I bought it. And all this has been done by loggers, factory workers, drivers, sales persons and others, who required the services of yet other people such as mechanics and caterers in order to do their jobs. But then, all these people have been brought into existence by their parents, who themselves …

There is simply no end to what has gone into this particular chair. Even the simplest chair, in other words, is not an independent reality. Having come into existence because of numerous causes, it exists as the nexus of all of them. Applied along such lines,

Indra’s net provides an

“instrument for the achievement of balance and depth in understanding and, moreover, for the avoidance of one-sided views”.[6]

There is yet more to our chair. It may be seen as an economic object, a status symbol and a piece of furniture, and perhaps also as an antiquity or firewood. But each of these perspectives by itself elicits no more than one aspect of its totality, while the other perspectives are hidden.

Yet, the Huayan school insists,

“the display of this by no means annihilates that. On the contrary, at the very moment when this is displayed, all the infinite that’s are simultaneously and secretly established without the slightest hindrance or obstruction. It is a great pity that the human mind can only function in a one-at-a-time, from-one-level pattern, thus deprived of the opportunity of seeing the infinite versions of a given thing at once”.[8]

The mirror metaphor: not bound by a specific perspective

The Huayan school teaches us to be ‘round’, that is, not bound by a specific perspective. The obstacle that stands in the way of a round view is our ego,

“a persistent tendency to cling to a small, enclosed self and its interests. Its essence is to exclude, its function is to separate”.[9]

Fazang’s mirrors[7] teach several things. The mirroring process takes place directly, not mediated by something else. A mirror mirrors, and when it does, it does so fully and completely ―

“it goes after nothing and welcomes nothing, it responds but does not store’.[10]

This exemplifies the unimpeded interconnection of the phenomena that the sutra speaks of. But not only the Huayan sutra; unimpeded interconnection is found in all Buddhist schools in one way or another.

The mirror metaphor conveys the primordial accord and mutual resonance of things in the world. And also, if scratched or dirty a mirror won’t be able to function adequately and the image shown cannot but be partial and distorted.

This demonstrates the disturbing role of the volitional intentions (fourth aggregate), which by and large come down to the Buddhist conception of the ego.

Whenever ego, self, or I interferes, as it cannot but do being itself the interfering volitional intention, the mirroring is disturbed and one-sided. But when the isolating sense of I is gone, awareness of the all pervading interconnection between all things arises.

The Huayan school has expressed this Buddhist insight as

“one in all and all in one’, and ‘one is all and all is one’.

Indra’s net has demonstrated the Huayan view of the relation between the phenomena as interdependent and interpenetrating without however, cancelling them out. Although their relativity is stressed, the phenomena do by no means disappear in an impenetrable fog of mutual dependence and interpenetration.

This could be summarised by saying that the sutra sees the phenomena as separate yet identical, and at the same time as identical, yet separate.

Having dealt with the phenomena-phenomena level we are still left with the phenomena-principle level.

The metaphor of the golden lion

How does li fit into the overall Huayan picture?

In order to help empress Wu understand this dimension of the unimpeded interconnection propounded by his school, the resourceful Fazang thought of yet another didactic devise, the metaphor of the golden lion[11].

In this metaphor gold symbolises the principle (li) and the lion a phenomenon or form (shi).

The relation between principle and form may be explained as follows. While the principle as such is formless it is inherent in all forms. Gold may be shaped into the form of a lion. But since the lion is merely a form it has no reality of its own ― it is entirely gold.

Hence, the existence of the lion is wholly dependent on the existence of gold. No gold, no lion; without the principle there can be no phenomena or forms.

On the other hand, since the lion represents the form of the gold the latter cannot exist without the former. Thus, form reveals principle, and gold and lion co-exist harmoniously. Although they are merged together this impedes neither from being itself.

“One can see the golden lion as a lion, and one can see it as gold, and one can see both, and one can see neither. When the mutual conditioning of gold and lion is in harmony, the dichotomy of Li and Shih is gone; words are useless, the mind is at rest. Reality is appearance, appearance is reality. The gold is the lion, the lion is the gold”.[12]

In other words, just as the relation between the phenomena among themselves the relation between phenomena and principle is one of identity yet separation, and separation yet identity. Li and shi are mutually conditioned.

The metaphor of the golden lion also demonstrates why the Huayan school qualifies as a characteristically Chinese school of Buddhist philosophy.

The reason is that the principle (li) is not located in a separate world, a higher metaphysical or over-world if you please, but is conceived as inherent in the phenomena (shi). The principle operates and is to be found in this world.

Although it is often taken as propounding a purely intellectual Buddhism, what Huayan wants to convey is not just to cognitively understand the interconnection of all phenomena, and phenomena and principle but to actually live this insight.

Chan

Bodhidharma came from the West

For all its lofty images and breathtaking scope the Buddhism of the Huayan school appeared to be highly Chinese in its concreteness. Nevertheless, in this respect the Chan school goes even further. This is probably the reason why it is often called the most Chinese form of Buddhism.

The earliest beginnings of the Chan school are foggy. When it began to emerge, Buddhism had already had four or five centuries to take root in Chinese soil and was solidly established.

There seems thus to have been little reason for an Indian meditation master to come from the West and set himself up as yet another teacher. But this is what the tradition tells us about Bodhidharma, a largely legendary character about whom nothing is known but who is assumed to have died in 532 at a ripe old age, which most accounts put at 150. He is said to have used not a single word in transmitting his teaching.[13]

The oft-quoted stanza attributed to him was not formulated until the Tang dynasty. It runs as follows,

“A special transmission outside the teachings;

Not standing on words and letters.

Directly pointing to the human heart,

Seeing into its nature and awakening.”[14]

When Chan began to be organised as an independent school it needed a history which would align it with the tradition of the already established Buddhist schools. It is not surprising therefore that a retrospective quality pervades the Chan tradition, McRae notes. Studying Chan history one deals

“not so much in facts and events as in legends and reconstructions, not so much with accomplishments and contributions as with attributions and legacies”.[15]

Bodhidharma the twenty eighth Indian patriarch and the first patriarch of Chan

Consequently, Bodhidharma went down in history as the twenty eighth Indian patriarch and the first patriarch of Chan.

After Bodhidharma four successive patriarchs seem to have carried on the tender Chan school: Huike (487-593), Sengcan (d. 606), Daoxin (580-635/651), and Hongren (602-675), who are traditionally presented as an unbroken line of master-disciple relationships although there is much historical uncertainty on this score.

This also applies to the third patriarch, Sengcan who has become known as the author of On trust in the heart (Xin xin ming) although it was probably produced during the Tang dynasty.

But from a practice point of view there is little reason to worry about Chan’s historical uncertainties. In view of what has been said about the tendency of the heart-mind to incline to either of two sides it is more pertinent to note Sengcan counsel about picking and choosing.

The first four lines of Trust in the heart run as follows,

“The Perfect Way is only difficult for those who pick and choose;

Do not like, do not dislike; all will then be clear.

Make a hairbreadth difference, and Heaven and Earth are set apart;

If you want the truth to stand clear before you, never be for or against.”[16]

Not only is this yet another instance of the injunction to avoid one sidedness but it can also be argued that however different they may seem, ultimately the teachings of Chan and Huayan amount to the same: one must be ‘round’.

To be round is to be free from specific points of view and limited perspectives. Not inclining toward any perspective, things are seen from all perspectives at once. Recall that the Huayan school is based on an orientation toward totality.

“Totality is a great harmony of the co-existence of all [perspectives]”.[17]

What is the Buddha?

Chang exemplifies this with the Chan story of a monk who asked Mazu what the Buddha was and on hearing the answer, ‘your mind is Buddha’, gained enlightenment. But after many years he was informed that Mazu had changed his teaching to ‘neither mind nor Buddha’.

The monk said,

“Let him have his neither mind nor Buddha, I still hold my ‘mind is Buddha’”.

Being informed of this reaction, Mazu was pleased and said that the monk had ripened.[18]

The monk had ripened to roundness because he was obviously not stuck in one point of view and did not become confused by Mazu’s change to another perspective.

Tang dynasty: Buddhism an exceedingly rich and powerful high church

By the time of the Tang dynasty Buddhism had developed a well entrenched position in Chinese society, amounting in fact to an exceedingly rich and powerful high church, maintained by the government at enormous expense.

Its dignitaries enjoyed a wealth of privileges, such as exemption from forced labour and taxation, and when engaged in economic activities did not feel above charging usurious rates.

Systematic persecution

There had been protests before but in 845 this incited systematic persecution of the Buddhist church. Nearly 5000 temples were destroyed (along with a number of Nestorian and Zoroastrian ones for good measure), some 250,000 monks and nuns were forced to return to lay life, and properties were confiscated.

Although the anti-Buddhist regulations were already reversed after one year, only the Pure Land and Chan schools survived, the latter becoming the dominant school of Chinese Buddhism. None of the other schools ever recovered.

Although it did not emerge completely unscathed from the persecutions, Chan is the only school that was never interfered with by the government. One reason is political. In the early days the patriarchs and their students lived tough itinerant lives that were unlikely to attract much official attention.

Although this changed during the fourth patriarch, the monasteries that came to be established tended to be simple and located in remote places, while the monks earned their own livelihood instead of begging.

Also important was that the governors of the out-laying regions where many monasteries were found were often of foreign origin and therefore treated rather off-handily by the central government. They did not feel much inclined therefore to obey its decrees. Moreover, many were Chan students themselves.

The Diamond sutra

According to the sutra bearing his name, the sixth patriarch, Huineng (638-713) and his widowed mother suffered extreme poverty. One day, while he was selling firewood, he happened to hear one of his customers read parts of the Diamond sutra[19].

We are told that his eyes were opened immediately, which prompted him to try and find the fifth patriarch.

Hungren, the fifth patriarch

But Huineng’s first encounter with Hungren was not all that encouraging. He was told that a barbarian from the south like him could never become a Buddha. Undaunted, the allegedly uneducated boy quoted from the Diamond sutra that

“although my barbarian’s body and your body are not the same, what difference is there in our Buddha nature?”.[21]

The fifth patriarch[20] got the message but decided to keep silent and put Huineng on the humble job of threshing rice, which prompted him, the tradition has it, to wear a heavy stone around the waist to add weight.

Receiving no specific instruction, the poor, illiterate, slight boy worked in the threshing shed for eight months. It must have been a fruitful period.

The succession

One day, the fifth patriarch, getting old and wanting to settle his succession asked the monks to produce a verse. The one who presented the deepest insight would become his successor. Since they were all convinced that this could only concern the head monk none of them even bothered to try and compose a verse.

The head monk himself however, was hesitant about his insight and waited until the dark of the night to brush his verse on the wall of a corridor without anyone else knowing about it.

“The body is the Tree of Awakening,

The heart a bright mirror;

Always wipe it carefully

So that no dust can settle.”[22]

Next morning, having read it all the monks thought this was a splendid verse and that the succession had been settled. The fifth patriarch too judged it to be fine. The head monk’s verse became the talk of the monastery and eventually also reached Huineng in the threshing shed.

Huineng, the sixth patriarch

Having had one of the monks read it to him, he asked him to write the following verse next to it,

“There is no Tree of Awakening;

The bright mirror has no stand;

When all is emptiness

[in later works: From the beginning not a thing is]

Where then could dust settle?”[23]

Because he feared to arouse the jealousy of the monks, the fifth patriarch handed Huineng the patriarchal robe in the middle of the night and urged him to flee south.

Nevertheless, the sixth patriarch was pursued and finally overtaken by a monk, who asked him for the robe. Without a moment of hesitation Huineng handed this sign of transmission over. But on finding that it was too heavy for him, the monk had a change of heart asked for instruction.

For a number of years, Huineng ripened in South China. On his re-emergence he started teaching and soon afterwards had gathered a couple of thousand monks and laymen.

After a fairly short teaching period, on his deathbed, he detailed the Chan practice.

“If you are only peacefully calm and quiet, without motion, without stillness, without birth, without destruction, without coming, without going, without judgments of right and wrong, without staying and without going ― this then is the Great Way”.[25]

Clearly, there is nothing here that does not fit in with the practice of self-cultivation as presented in the Mean and the Daoist classics.

The four teachers

Although their relations with the sixth patriarch are again uncertain, traditionally the line of his successors is formed by Mazu (709-788), Baizhang, Huangbo (d. 847), and Linji (d. 867).

The four teachers are represented in the Chan literature by collections of stories, discourses, and sayings, in which the lofty heritage of India has been put in pretty straightforward colloquial Chinese called baihua (white language), conveying stunningly concrete and outright physical ways of teaching[26].

Understanding of gongan

Indeed, countless stories testify to the perplexing speed with which the Chan masters reacted to the doubts and questions of students struggling to escape from their incessant deliberations. In the 1950s, when Chan began to become known in the West, it tended to an unfortunate popularity with hippies and New Agers because of its apparently unconventional teachers, aggravated by an understanding of gongan, better known by their Japanese name of koan, as mysterious riddles and mind busters.

However, it is not exotic pedagogical devises that abound in the exchanges between teacher and student. The teachers simply reacted to the demands of the situation that had been set up by the perplexed student and, following the lines laid down by Bodhidharma’s verse, did so in an disconcertingly direct way.

Hence, the shouting and beating, but also the humorous paradoxes and nonsensicalities ― virtually everything was used to shock the student out of his inclinations. Looked at thus, the seemingly irate behaviour of the Chan teachers, although not rational in the sense of reasoned-out, does stand to reason.

Moreover, as Jullien points out, the seeds of this indicative way of teaching may already be found in Confucius and his followers.[27]

It should be realised that Confucius too, did not teach an abstract truth but tried to guide human conduct towards accord with the present moment. Quite like other Chinese teachers we have met Confucius did not teach a creed ― he just indicated the Way.

As he said,

“Only one who bursts with eagerness do I instruct; only one who bubbles with excitement, do I enlighten. If I hold up one corner and a man cannot come back to me with the other three, I do not continue the lesson”

Analects Bk. VII, 8.[28]

Since Confucius did by no means try to convert the student it was of the essence that the latter was enabled to find the Way by his own lights. Just a few words or, better still, a silent pointing should therefore suffice. True enough, many instances of Chan teaching seem pretty drastic (see story below) but does that make them basically different from the indicative approach taken by Confucius?

“Ummon was not satisfied with his knowledge of Buddhism which had been gained from books, and came to Bokuju to have a final settlement of the intellectual balance-sheet with him. Seeing Ummon approach the gate, Bokuju shut it in his face. Ummon could not understand what it all meant, but he knocked and a voice came from within: ‘Who are you? My name is Ummon. I come from Chih-hsing. What do you want? I am unable to see into the ground of my being and most earnestly wish to be enlightened.’ Bokuju opened the gate, looked at Ummon, and then closed it. Not knowing what to do, Ummon went away. This was a great riddle, indeed, and some time later he came back to Bokuju. But he was treated in the same way as before. When Ummon came for a third time to Bokuju’s gate, his mind was firmly made up, by whatever means, to have a talk with the master. This time as soon as the gate was opened he squeezed himself through the opening. The intruder was at once seized by the chest and the master demanded: ‘Speak! Speak!’ Ummon was bewildered and hesitated. Bokuju, however, lost no time in pushing him out of the gate again, saying, ‘You good-for-nothing fellow!’ As the heavy gate swung shut, it caught one of Ummon’s legs, and he cried out: ‘Oh! Oh!’ But this opened his eyes to the significance of the whole proceeding.”[29]

The teaching of Linji

In the teaching of Linji[30], Chan probably attained its zenith as the most Chinese form of Buddhism. From his rough, utterly down to earth sayings Linji comes to the fore as a ‘true man’. This expression was first used by Zhuangzi.

The true man is nothing special, except that by virtue of having neither rank nor status he eludes qualification. Confucius would not have liked this because in traditional China everyone had a rank in the social hierarchy.

But like many Hellenistic philosophers the Chan people of old were what the ancient Greeks called atopoi (unclassifiable).

To live in the present moment

Above all however, Linji emerges as someone who lived in the present moment. If, as he counselled, the heart-mind is set at rest, there is no inclination or intention and thus, there is no going beyond the ‘now’.

“Followers of the Way, if you know that fundamentally there is nothing to seek, you have settled your affairs …

… Just put your heart at rest and seek nothing outside. When things come towards you, look at them clearly. Have faith in the one who is functioning at this moment, and all things of themselves become empty … Thus, (smoothly) functioning in response to the moment, what are you lacking….

… He who stands clearly revealed and distinct before your eyes, listening to the Dharma, this Independent Man of the Way lacks nothing at all … When the attitude of your heart does not change from moment to moment, this is called the living patriarch. For if it changes, then your essential nature and your actions come apart. But when your heart does not differ, there is also no difference between your essential nature and your actions …

I tell you this: There is no Buddha, no Dharma, no training and no realization. What are you so hotly chasing? … What are you lacking? Followers of the Way, the one functioning right before your eyes, he is not different from the Buddhas and patriarchs ….”[31]

- Ch’u, Ta-Kao. (Transl) (1937/1976) Tao te ching. London: Umwin.

- Chan, Wing-tsit. (1963). A sourcebook in Chinese philosophy. Princeton: Princeton U.P.

- Chang, Chung-yuan. (1975). Creativity and Taoism. London: Wildwood House.

- Chang, G.C.C. (1972). The Buddhist teaching of totality ― The philosophy of Hwa Yen Buddhism. London: Allen & Unwin.

- Cleary, Th. (1983) Entry into the inconceivable ― An introduction to Hua-Yen Buddhism. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

- Conze, E., Horner, I.B., Snellgrove, D., & Waley, (Transl). (1990). Buddhist texts through the ages. Boston: Shambala.

- Fairbank, J.K. & Goldman, M. (2006). China: A new history. Cambridge (MA): Harvard U.P.

- Fung, Yu-lan. (1937/1952). A history of Chinese philosophy, 2 Vols. (Transl Derek Bodde). Princeton: Princeton U.P.

- Fung, Yu-lan. (1960). A short history of Chinese philosophy. New York: Macmillan

- Hansen, C. (1989). Language in the heart-mind. In R.E. Allinson (Ed.).

- Jullien, F. (2000). Detour and access: Strategies of meaning in China and Greece (Sophie Hawkes, transl.). New York: Zone Books.

- Liu, Xiaogan (2003). Confucianism: Texts in Guodian bamboo slips. In A.S. Cua (Ed.). Encyclopedia of Chinese philosophy (pp. 149-153). New York: Routledge.

- Lloyd, G.E.R. & Sivin, N. (2002). The way and the word: Science and medicine in early China and Greece. New Haven: Yale U.P.

- McRae, J.R. (2003). Seeing through Zen: Encounter, transformation, and genealogy in Chinese Chan Buddhism. Berkeley: Univ. California Press.

- Piyadassi, M. (1991). The spectrum of Buddhism. Colombo: Karunaratne & Sons.

- Rahula, W. (1959). What the Buddha taught. New York: Grove Press.

- Schloegl, I. (1975). The wisdom of the Zen masters. London: Sheldon Press.

- Suzuki, D.T. (1962). The essentials of Zen Buddhism. London: Rider.

- Takakusu, J. (1947/1975)- The essentials of Buddhist philosophy. New Delhi: Oriental Books Reprint Corporation.

- Watson, (Transl). (1968). The complete works of Chuang Tzu. New York: Columbia U.P.

- Watson, (Transl). (2003). Zhuangzi ― Basic writings. New York: Columbia U.P.

- Williams, P. (1989). Mahayana Buddhism: The doctrinal foundations. London:

- Yampolsky, Ph.B. (Transl). (1967). The Platform sutra of the sixth patriarch. New York: Columbia U.P.

Notes

[1] Source in the Public Domain of the Avatamsaka Sutra, vol. 12, frontispiece in gold and silver text on indigo blue paper, mid 14th century – (화엄경 華嚴經 12권) Ho-Am Art Museum, Author Unknown; Source: http://www.asianart.com/exhibitions/korea/14.html

[2] Cleary, 1983, p. 23

[3] Read more on the Huayan School

[4] Williams, 1989, p. 124

[5] Read more on the Empress Wu Zetian

[6] Cleary, 1983, p. 38

[7] Read more on Fazang Infinity Mirror

[8] Chang, 1972, pp. 127-128

[9] Chang, 1972, p. 26

[10] Watson, 1968, p. 97

[11] Read more about Fazang and his philosophical metaphors.

[12] Chang, 1975, pp. 99-100

[13] Read more on Bodhidharma and see a depiction of this legendary figure.

[14] Adapted from Schloegl, 1975, p. 14

[15] McRae, 2003, pp. 14-15

[16] Translation Waley, in Conze et al., 1990, p. 295

[17] Chang, 1972, p. 135

[18] Chang, 1972, p. 131

[19] Source: Chinese translation of the ‘Diamond Sutra’. The frontispiece to the world’s earliest dated printed book. This consists of a scroll, over 16 feet long, made up of a long series of printed pages. Printed in China in 868 CE, it was found in the Dunhuang Caves in 1907 (cave 17).

[20] Read more and see depictions of The fifth Chan patriarch carrying a hoe — Marjeyama Collection.

[21] Yampolsky, 1967, p. 128

[22] Adapted from Schloegl, 1975, p. 15

[23] Adapted from Schloegl, 1975, p. 15

[24] Source in the Public Domain of The Sixth Patriarch Huineng, carrying a rod across his shoulder. Southern Song Dynasty, 13th century. (Gotoh Museum), Tokyo. Author Zhiweng.

[25] Yampolsky, 1967, p. 181

[26] Read more and see depictions of Ten Verses on Oxherding (1278)

[27] Jullien, 2000, pp. 199, 270

[28] Read more on basic concepts and the Analects by Confucius

[29] Suzuki, 1962, pp. 197-198

[30] Read and see more on a portrait of Rinzai (Linji)

[31] Schloegl, 1976, pp. 28, 33-34, 37-38, 44-45