Hans van Rappard

9 ― From: Rappard, H. van (2009). Walking Two Roads ― Accord and Separation In Chinese and Western Thought. Amsterdam: VU University Press. Chapter 4, pp. 103-115.

part 1 – part 2 – part 3 – part 4 – part 5 – part 6 – part 7 – part 8 – part 9 – part 10 – part 11 – part 12 – part 13 – part 14 – part 15 – part 16 – part 17

Laozi

According to the traditional view expounded by Sima Qian (ca. 145 BCE-ca. 86 BCE), a historian, Laozi was a contemporary of Confucius whom he once met, while his Daodejing was the first philosophical work in Chinese history.

In scholarly circles this view has long been challenged until archaeological finds in the villages of Mawangdui (1973) and Guodian (1993) yielded support for it. Hence, the book might date from the fourth instead of the third century BCE, while oral versions of (parts of) it may have existed long before.

Daodejing, the Laozi

What also remains uncertain is whether the enigmatic Daodejing (which may have seen as many as three hundred translations as compared to maybe thirty of the Analects) was written by a single author or perhaps compiled from various sources. However, the authorship problem will be left to the specialists.

Whoever or however many authors are responsible for the Daodejing is quite irrelevant for present purposes. The five thousand character book, written in terse, rhythmic and sometimes rhyming language has been in existence for more than two millennia, and is conveniently ascribed to one or more authors called Laozi. The Daodejing will henceforth be referred to as the Laozi.

Zhuangzi

Although Zhuangzi remains a misty character too, it is fairly certain that there has actually been a master Zhuang, whose personal name was Zhou.

According to Sima Qian, he lived between 370 and 300 BCE and worked in a lacquer garden.

The Zhuangzi

Master Zhuang produced a more substantial book than his comrade in Daoism, comprising fifty two chapters in more than hundred thousand characters. But later commentators, notably Guo Xiang (d. 312) have deleted much, leaving some seventy thousand characters in thirty three chapters.

In its present form the book is divided in the so-called

- Inner chapters (1-7) which have likely been written by the Master himself,

- the Outer chapters (8-22) and

- Miscellaneous chapters (23-33), produced by later authors.

Zhuangzi himself appears in a number of anecdotes but these offer little in the way of a biography. A good friend of his, the sophist Hui Shi is also mentioned and castigated for wasting his time on clever nonsense. But after his death Zhuangzi lamented that he had been deprived of the one person on whom he could sharpen his wits.

Given the shaky facts about his life, it is not surprising that scholars do not agree on the relation between the two defining figures of Daoism. Currently most assume that Zhuangzi inherited the doctrine from Laozi. The authors of the book bearing his name must have known the Laozi because they often quote or allude to it. But it has also been argued that Zhuangzi was the original Daoist. As in the case of Laozi however, we will not bother about these issues and use Zhuangzi’s splendid work,

“one of the greatest poems of ancient China”,[2]

as if it might unproblematically be ascribed to him.

Daoist classics: the Daodejing and the Zhuangzi

Unless otherwise stated all quotations of the Chinese classics in this chapter have been taken from Chan’s Sourcebook[4]. The beginning of the first chapter of Laozi’s philosophical poem Daodejing says,

“The Tao (Way) that can be told of is not the eternal Tao;

The name that can be named is not the eternal name.

The Nameless is the origin of Heaven and Earth;

The Named is the mother of all things.”

And according to the first lines of chapter twenty five translated by Chan, and the final lines as rendered by Ch’u Ta-Kao[5],

“There was something undifferentiated and yet complete,

Which existed before heaven and earth.

Soundless and formless, it depends on nothing and does not change.

It operates everywhere and is free from danger.

It may be considered the mother of the universe.

I do not know its name; I call it Tao

…

Man follows the laws of earth;

Earth follows the laws of heaven;

Heaven follows the laws of Tao;

Tao follows the laws of its intrinsic nature.”

In Daoism a distinction is found between you (yu, being) and wu (non-being), and between you-ming (having name, nameable) and wu-ming (not-having name, unnameable). The former distinction is an abbreviation for the latter.

It follows that being (you) is a matter of having a name or being nameable (you-ming), while things that have no name and thus cannot be named (wu-ming) do not exist (wu).

Now, to assign a name to something, for instance ‘chair’ to the chair that is actually here in my room, means that it is discriminated from the other pieces of furniture and whatever else happens to be around. Because of its having-a-name the chair may be singled out from other ‘nameables’ and thus lifted out of its furnished-room context.

In other words, naming entails that the totality of this context is carved up to some extent. Indeed, Graham and Hansen point out, Laozi saw language as a system of distinctions. Thus, a name (ming) picks out a part of reality and excludes the rest. The point of departure is the whole. Chinese thinking, Graham says, tends

“to divide down rather than to add up [and]to think in terms of whole/part.”[6]

The Laozi also took the whole for its starting point. Chapter thirty two, as rendered by Fung and Lau,[8] teaches that once the uncarved block is cut, there are names. And because the ten thousand things all have names the block is pretty much carved up indeed. However, and here we come across the kind of paradoxes that Daoism is loaded with, there is one name that is not really nameable. It is not difficult to see what name this is ― indeed, the block-name.

Just consider: if having-names entails carving-up, then that-which-is-carved-up cannot itself have a name. If the block were nameable, there would have to be something from which it is discriminated by this name but in that case it would not make sense to speak of the block being carved up because of its being named. Indeed, this would be a rather half-way starting point: why mention the block ― why not the larger ‘thing’ the block itself had been carved from or a smaller thing that had been carved from it?

No, the point of departure of the Laozi is the block and this informs us about the consequences of there being names. Yet, since ‘block’ is itself a name we are warned ― in the first chapter where Dao and Name are mentioned instead of block ― that as long as we think there is actually something that can be named Dao, Dao is brought down to something nameable, that is, something that is carved off from the real, all-encompassing Dao. The same goes for the names and the Name (Ming). Hence, Dao and Ming are no names or rather, they are no ordinary, nameable names but unnameable and in that sense nameless names. However mysterious and paradoxical this may seem, it follows from the discriminating, carving-up nature of words. Medieval theologians trying to speak of the ultimate reality designated by the word God had a similar problem on their hands and sometimes found a similar solution.

It can now be understood why the first chapter of the Laozi says that the nameless is the origin of heaven and earth. Actually, this is an almost logical statement because if the things in the world require names in order to be, their ultimate source must be that which is unnameable. Moreover, since names discriminate and put things in opposition to each other, bringing things into existence means for the unnameable Dao that it issues forth an endless chain of opposites, the first of which is heaven ― earth.

In chapter forty one reads

“All things in the world come into being from Being [you];

and Being comes into being from Non-being [wu].”

Chapter forty two elaborates on this, saying

“From Dao there comes one.

From one there comes two.

From two there comes three.

From three come all things.”

Incidentally, it is not clear why the author(s) of the Laozi felt it imperative to add ‘three’ instead of saying that all things come from two but it may refer to the trinity of yin and yang, and the productive harmony resulting from their interaction.[9]

Be this as it may, a similar view is found in Zhuangzi.

“In the Great beginning, there was nonbeing; there was no being, no name.

Out of it arose One; there was One, but it had no form.”[10]

Clearly, for both Laozi and Zhuangzi One forms the transition from the formless Dao as the origin of everything to the ten thousand forms or things. Though One is still formless it is different from Dao in that the multiplicity manifest in all things is latently present in it.

Commentary by Wang Bi

A later Daoist, Wang Bi (226-249), who has probably written the most brilliant commentary on the Laozi noted with concern to chapter forty two,

“All things and shapes may be reduced to oneness, but from what derives this oneness? It derives from non being.”

Now, it would seem that since Dao produces one, it must be superior to it but, Fung points out, according to Wang Bi

“the ‘one’ stands in opposition to ‘multiplicity’, for whereas ‘multiplicity’ consists of all ‘existing things’, the ‘one’ is the ‘origin from which come’ all these existing things. This means that oneness is itself the Tao.”[12]

Wang Bi’s interpretation has significant consequences. It precludes a conception of Dao as the transcendental origin of the ten thousand things because it is now seen as present in the multiplicity of things as their principle. Dao, in other words, is immanent and in the world rather than transcendent and above or behind it.

Dao is everywhere, it is present in all things. Hence, Zhuangzi could say, later followed by many Chan masters, that there is no place where the Way does not exist. It is in an ant, in grass, in tiles and shards, and it is in “piss and shit.”[13]

But Wang Bi’s commentary tells us more. It also means that the beginning of all things (Dao) is not just a temporal beginning, a single moment in time, but that the beginning remains active as their principle (Li). Because according to this interpretation Dao keeps on nourishing and nursing things rather than abandoning them once they have come into existence, it may be called, as chapter twenty five of the Laozi says,

‘the mother of the universe’.

Reversion is the action of Dao

All things in the world are in flux and continuous change but this process is governed by invariable rules. The most fundamental rule holds that

“Reversion is the action of Dao”

Laozi chapter forty.

This is very much in line with the Yijing according to which yin is continuously alternating with yang, and vice versa. Since no difference is seen between the world of nature and the world of man, the invariables also pertain to human conduct.

A homely example is found in chapter four of the Zhuangzi,

“When men meet at some ceremony to drink, they start off in an orderly manner, but usually end up in disorder, and if they go on too long they start indulging in various irregular amusements. It is the same with all things. What starts out being sincere usually ends up being deceitful. What was simple in the beginning acquires monstrous proportions in the end.”[15]

In other words, when things are allowed to go too far they will likely revert to their opposites.

Chapter twenty-nine of the Laozi warns that the sage

“discards the extremes, the extravagant, and the excessive”

and it is not difficult to see why. Once things have developed to the extreme, the yin-yang relation demonstrates, they have perforce reached the point where they are bound to revert.

Although phrased differently and in a different context, the point made by the Daoist sages is not new. Recall that in a previous paper Zhu Xi described the Confucian mean (zhong) as not being one-sided. Now, would it be wrong to infer that, generally speaking, far-going tendencies, such as the extreme and the others that the sage is wise enough to discard are shining examples of becoming one-sided? Indeed, one might think, one-sided in the extreme!

Natural behaviour

The behaviour of the Daoist is often called natural and many stories warn against acting in an unnatural, arbitrary, or contrived manner. The classic example is the farmer who pulls up his rice plants to expedite their growth but only succeeds in killing them. All this seems to come down to not inclining to one side, to guarding oneself against choosing one side over the other. Should one incline to white, thus excluding the opposite black side the naturalness of one’s action is lost and balance is gone.

“He who stands on tiptoe is not steady”

chapter twenty-four of the Laozi warns.

The trouble is that in daily life people habitually incline to one side because they all strive or intend to achieve goals that are not yet there, rather than stay in accord with what the present moment allows.

It is easily grasped that not inclining entails that one should restrict one’s activities to what is actually needed to achieve a certain goal, with no excess effort. Therefore, when acting one’s efforts are to be fine-tuned to what is required under the circumstances and this is where de comes in.

Power ― de ― in both the physical and the moral sense of the word

De ― the de in ‘Daodejing’ ― is what all the ten thousand things, including human beings, have been imparted with by Dao, their origin. De means power in both the physical and the moral sense of the word. In the latter case we speak of virtue. The de of inanimate as well as animate things constitutes what they naturally are. Thus, in view of what was said in the first chapter of the Mean, what Dao has conferred to human beings may be called human nature, or as it is called in the Laozi, virtue (de).

“Dao produces them (the ten thousand things). Virtue fosters them.”

Laozi, chapter fifty one

Therefore, to say that one should be careful to not incline, entails that one’s actions should be tuned to what is naturally called for to achieve a particular goal. Natural, then, means to follow one’s de without unnecessary effort, without overreaching oneself, or, yet differently, without becoming one-sided. But this also means that someone who really follows de carefully avoids taking good and bad as opposites. In the Laozi this is called simplicity (pu). Dao is likened to a block uncarved and silk unwrought, that is, materials that are still in the original ‘simple’ state that obtained prior to any working contrived with a particular goal in mind.

Although the above entails a Daoist reading of the Confucian Mean ― of which there have been many ― Laozi and Confucius did by no means see eye to eye. To give but one example, the former despised Confucian human-heartedness (ren, jen) because such virtues could in his view be nothing but degenerations from Dao and de.

Chapter thirty-eight of the Laozi says,

“only when Tao is lost does the doctrine of virtue arise.”

It appears that as long as twenty odd centuries ago people also tended to cherish too many desires and to be too clever for their own good because this is mentioned in the Laozi as the reason for the decline of Dao.

“There is no calamity greater than lavish desires”,

it is said in chapter forty-six.

It has been noted that just as in Confucianism, in Daoism the ruler is addressed because this school was also very much concerned about the turmoil and chaos that prevailed in China prior to the unification by the Qin dynasty. Both schools agreed that ideally states should be run by sages but, not surprisingly, the substance of their wisdom was construed along different lines. Simply put, the Confucian sage-ruler is expected to do things for his people, whereas his Daoist colleague knows only too well that the cause of the dire state of the nation is precisely that too many things are being done already.

Therefore, in chapter three the Laozi says,

“… in the government of the sage,

He keeps their hearts vacuous,

Fills their bellies,

Weakens their ambitions,

And strengthens their bones,

He always causes his people to be without knowledge (cunning) or desire,

And the crafty to be afraid to act.

By acting without action [wuwei], all things will be in order.”

Since small children are assumed to not yet have acquired much knowledge nor developed many desires they form an analogy for the subjects of the sage-ruler.

In chapter forty-nine one reads,

“The sage, in the government of his empire, has no subjective viewpoint.

His mind forms a harmonious whole with that of his people.

They all lend their eyes and ears, and he treats them all as infants.”

The simplicity and ignorance of the people are characteristics that every grown human being should try to preserve because they signify that one hasn’t yet strayed from one’s nature (de).

According to chapter fifty-five,

“He who possesses virtue in abundance

May be compared to an infant.

…

He may cry all day without becoming hoarse,

This means that his (natural) harmony is perfect.

To know harmony means to be in accord with the eternal.”

Thus, the sage-ruler keeps his people ― and himself ― ignorant or natural. But although nature is highly important in Daoism, ultimately it is not so much the actual mountains and rivers that the word refers to as ‘natural’ in the sense of being or behaving in a natural way. Being natural one is in harmony with the situation one finds oneself in.

Wuwei, ziran

Phrased negatively, being natural involves that one does not try to go against the natural course of things, that is, one does not try to interfere. Putting the matter thus brings being natural close to what is meant by the Daoist expression wuwei. To the Daoists the phenomena of nature provide an inexhaustible store of examples of non-interference.

In Chinese ‘nature’ is written as ziran, using the characters zi (self) and ran (so), which combined (self-so) mean happening just so, just of itself ― in other words, natural. Therefore, Daoism counsels its practitioners to act without trying to interfere, that is, to simply resonate and be in tune with whatever presents itself, and this holds for situations in the natural as well as the social world.

We return to ‘ignorance’. Daoist ignorance is not an asymmetrical matter of the ruler trying to keep his subjects dumb and down while he himself is way above them enjoying supreme knowledge and satisfying his many desires. Rather, the Daoist ruler stays carefully in accord with his original nature, which allows him to set an example for his people.

This demonstrates that at least in this respect the difference between the Confucian Mean and the Laozi is not quite so large as one might think. In earlier days, prior to the unification of China by the Qin dynasty (221-206 BCE) the differences between Confucianism and Daoism may even have been hardly noticeable.

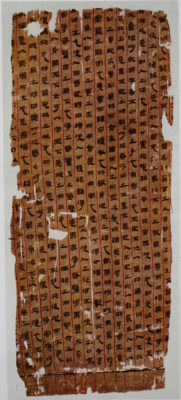

Guodian bamboo slips

In 1993 about seven hundred inscribed bamboo slips were excavated from a tomb in the village of Guodian. The tomb, dated from not later than 278 BCE, contained sixteen texts, two Daoist and fourteen Confucian ones.

Scholars think it is striking that Confucian and Daoist texts were unearthed from the same tomb because this lends little support to the opposition between the two schools with which we are so familiar from later times. Even more striking is that in some passages a sharing of ideas is found. Although there are still many uncertainties the Guodian texts

“suggest that perhaps there was no strong tension or distinction between Confucianism and Daoism in pre-Qin China.”[19]

Basic similarity between Confucianism and Daoism

Later the two schools have to some extent parted the ways or perhaps were labelled differently for political reasons but remarkably, they did not grow apart to such an extent that Daoism (along with Buddhism) became incapable of influencing Confucianism.

More than that, during the Song and Ming dynasties many Confucians even felt that there was no essential difference with Daoism. This should not surprise us. In spite of many differences both movements share a lot of common ground.

One of the more important points of agreement is that although at first sight the Confucians seem to be much more involved with human society than the Daoists, many of whom preferred to keep themselves to themselves in the quiet contemplation of nature, putting the matter thus entails a dichotomy that, as noted already, does not obtain in Chinese thinking.

Both see the human being as essentially forming part of nature. Another basic similarity between Confucianism and Daoism may be found in the way that both address the central problem of Chinese philosophy as to how the world is to be ordered and set at peace.

The ruler has to order his heart-mind

The Mean as well as the Laozi admonish the ruler to order his heart-mind because once that has been achieved the people (in the Laozi), or the ruler’s family, kingdom, and the entire world (in the Mean) will order themselves.

Moreover, ordering one’s heart-mind is only possible by following the Way (Dao), which in both texts comes down to harmonising oneself with what Dao (in the Laozi) or Heaven (in the Mean) have imparted to us.

Heaven –> human nature of ruler –> family, kingdom, world

Dao –> De of ruler –> people

But how do the sage-ruler and the Daoist hermit, who might well be a retired civil servant for that matter become and stay in accord with their original nature? What does their practice of self-cultivation and transformation entail?

Actually, the answer has already been treated above: the way of men may be rendered shortly and sweetly as ‘don’t incline ― don’t be one-sided’.

Confucius’ Analects remained silent on practice other than ‘learning’. In the Laozi not much is found either but in what was later called Daoist philosophy to distinguish it from Daoism as a folk religion an elaborate kind of ‘yoga’ was developed, comprising breathing exercises and other practises designed to further longevity.

Yet, what little is said in the Laozi on self-cultivation squarely comes down to ‘don’t incline’.

For instance, the first lines of chapter sixteen advise to

“Attain complete vacuity/ Maintain steadfast quietude.”

What is meant by quietude? The restfulness of a holiday beach? Unlikely. Even if the doctrines expounded in the Laozi are

“very easy to understand and very easy to practice”,

none in the world actually do so (chapter seventy) and it is not difficult to see why this should be so now that we know how much simplicity is valued.

In chapter thirty-seven one finds,

“Simplicity, which has no name, is free of desires. Being free of desires, it is tranquil.”

And chapter twenty says,

“I alone am inert, showing no sign (of desires),

…

I alone seem to have lost all.

Mine is indeed the mind of an ignorant man,

Indiscriminate and dull!

…

I alone make no distinctions.

I seem drifting as the sea;

Like the wind blowing about, seemingly without destination.

The multitude all have a purpose;

I alone seem to be stubborn and rustic.

I alone differ from others,

And value drawing sustenance from Mother (Dao).”

What is advocated is letting go of everything that makes people incline: distinctions, which will then be picked and chosen from, and intentional actions guided by ulterior purposes. Having accomplished this, Laozi seems to have lost all, but this entails no complaint. In a statement that may well have enraged countless Confucians we are told that whereas the pursuit of learning is to increase day after day,

“The pursuit of Tao is to decrease day after day”

Chapter forty eight.

Other translators have “losing” instead of decreasing and hence, to the extent that the word method is applicable here, the method conveyed in the Laozi may be described as ‘losing, and losing, and yet again losing’.

But then, what exactly is it that the Daoist had better lose, and why?

One does not have to be a Chinese recluse to appreciate the answer to this question, fust recall trying to sit quietly. As discussed in the second chapter of this essay, countless thoughts crossed the mind but even though they were not solicited many managed to capture the attention for a while until they were let go of in favour of a more juicy one. But once engaged by a particular thought a relation with it was established, that is, an attitude was assumed towards it. Even without the chair-experiment it is easily grasped that it is wellnigh impossible to avoid evaluating one’s thoughts once they appear on the scene. In other words, the moment one becomes aware of the given situation feelings of liking and dislikes tend to emerge. The feelings which Plaks, admittedly going beyond the text of the first chapter of the Mean called, ‘the markers of human existence: pleasure, anger, sorrow, and joy’, clearly imply a liking or disliking.

Most of us will try to avoid anger and sorrow and strive for as much pleasure and joy as can possibly be had. Choosing a different course would be frowned upon and yet, these markers are shining examples of what Zhu Xi called one-sidedness; avoiding sorrow and seeking for joy one cannot but ‘incline to one side’. Therefore, the Confucian gentleman is warned against letting the markers of human life arise unduly, while the Daoist practitioner sits and forgets and so loses them. In the Zhuangzi this is called the ‘fasting of the heart-mind’. In the following quotation fasting is explained by Confucius to his favourite student, Yan Hui. This is a literary trick often played by Zhuang zi; putting Confucius on the scene as a Daoist sage, he makes him the spokesman of his own ideas.

Yan Hui said,

“‘May I ask what the fasting of the mind is?’

Confucius said, ‘Make your will one! Don’t listen with your ears, listen with your mind. No, don’t listen with your mind, but listen with your spirit. Listening stops with the ears, the mind stops with recognition, but spirit is empty and waits on all things. The Way gathers in emptiness alone. Emptiness is the fasting of the mind’.”[22]

It is not difficult to appreciate that ‘inclining to one side’ does not much contribute to making the will one. But perhaps Confucius’ counsel still seems a little too abstract. Let’s turn to chapter nineteen and listen to woodworker Qing, who on having carved an exceedingly beautiful bell stand is asked by the marquis of Lu what art it is that he has.

Qing replied,

“I am only a craftsman ― how would I have any art? There is one thing however. When I am going to make a bell stand, I never let it wear out my energy. I always fast in order to still my mind.

When I have fasted for three days, I no longer have any thought of congratulations or rewards, of titles or stipends. When I have fasted for five days, I no longer have any thought of praise or blame, of skill or clumsiness.

And when I have fasted for seven days, I am so still that I forget I have’ four limbs and a form and body. By that time, the ruler and his court no longer exist for me. My skill is concentrated and all outside distractions fade away. After that, I go into the mountain forest and examine the Heavenly nature of trees.

If I find one of superlative form, and I can see a bell stand there, I put my hand to the job of carving; if not, I let it go. This way I am simply matching up ‘Heaven’ with ‘Heaven’”

- Ch’u, Ta-Kao. (Transl) (1937/1976) Tao te ching. London: Umwin.

- Chan, Wing-tsit. (1963). A sourcebook in Chinese philosophy. Princeton: Princeton U.P.

- Chang, Chung-yuan. (1975). Creativity and Taoism. London: Wildwood House.

- Chang, G.C.C. (1972). The Buddhist teaching of totality ― The philosophy of Hwa Yen Buddhism. London: Allen & Unwin.

- Cleary, Th. (1983) Entry into the inconceivable ― An introduction to Hua-Yen Buddhism. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

- Conze, E., Horner, I.B., Snellgrove, D., & Waley, (Transl). (1990). Buddhist texts through the ages. Boston: Shambala.

- Fairbank, J.K. & Goldman, M. (2006). China: A new history. Cambridge (MA): Harvard U.P.

- Fung, Yu-lan. (1937/1952). A history of Chinese philosophy, 2 Vols. (Transl Derek Bodde). Princeton: Princeton U.P.

- Fung, Yu-lan. (1960). A short history of Chinese philosophy. New York: Macmillan

- Hansen, C. (1989). Language in the heart-mind. In R.E. Allinson (Ed.).

- Jullien, F. (2000). Detour and access: Strategies of meaning in China and Greece (Sophie Hawkes, transl.). New York: Zone Books.

- Liu, Xiaogan (2003). Confucianism: Texts in Guodian bamboo slips. In A.S. Cua (Ed.). Encyclopedia of Chinese philosophy (pp. 149-153). New York: Routledge.

- Lloyd, G.E.R. & Sivin, N. (2002). The way and the word: Science and medicine in early China and Greece. New Haven: Yale U.P.

- McRae, J.R. (2003). Seeing through Zen: Encounter, transformation, and genealogy in Chinese Chan Buddhism. Berkeley: Univ. California Press.

- Piyadassi, M. (1991). The spectrum of Buddhism. Colombo: Karunaratne & Sons.

- Rahula, W. (1959). What the Buddha taught. New York: Grove Press.

- Schloegl, I. (1975). The wisdom of the Zen masters. London: Sheldon Press.

- Suzuki, D.T. (1962). The essentials of Zen Buddhism. London: Rider.

- Takakusu, J. (1947/1975)- The essentials of Buddhist philosophy. New Delhi: Oriental Books Reprint Corporation.

- Watson, (Transl). (1968). The complete works of Chuang Tzu. New York: Columbia U.P.

- Watson, (Transl). (2003). Zhuangzi ― Basic writings. New York: Columbia U.P.

- Williams, P. (1989). Mahayana Buddhism: The doctrinal foundations. London:

- Yampolsky, Ph.B. (Transl). (1967). The Platform sutra of the sixth patriarch. New York: Columbia U.P.

Notes

[1] Source: Sima Qian

[2] Watson, 2003, p. 16

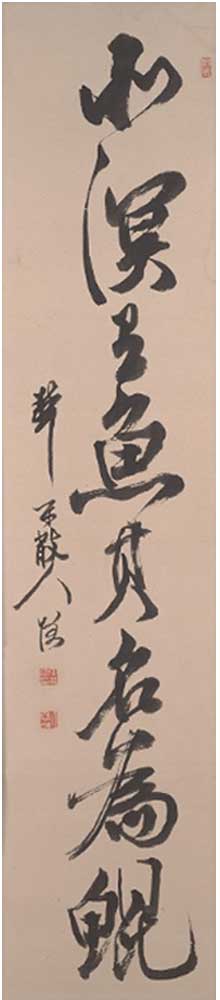

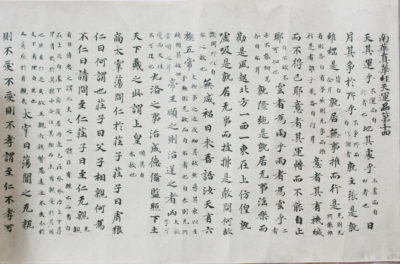

[3] Source: Calligraphy of the first sentence of the Zhuangzi: In the murky waters of the north there was once a fish, and his name was Kun.

[4] Chan, Wing-tsit. (1963). A sourcebook in Chinese philosophy. Princeton: Princeton U.P.

[5] Ch’u, 1976, p. 37

[6] Hansen, 1989, p. 80; Graham, 1989, p. 401

[7] Source: A part of a daoist manuscript, ink on silk, 2nd century BCE, Han Dynasty, unearthed from Mawangdui tomb 3rd

[8] Fung, 1960, p. 95; Lau, 1963, p. 37

[9] Fung, 1952, Vol. I, p. 179

[10] Watson, 1968, p. 131

[11] Source: 1770 Wang Bi edition of the Daodejing

[12] Fung, 1952, Vol. II, p. 183

[13] Watson, 1968, p. 141

[14] Source: Zhuangzi contemplates a waterfall

[15] Watson, 1968, p. 61

[16] Source: the character 德 (de) in the Shuowen seal script

[17] Source: Zhuangzi Dreaming of a Butterfly ― Lu Zhi (c. 1550)

[18] Source: Partial view of the Guodian Chu Slips (with side description and explanation in white) at Hubei Provincial Museum

[19] Liu, 2003, p. 152

[20] Source: Confucius meets Laozi

[21] Source: Tang dynasty manuscript of Tian Yun, Volume of Zhuangzi discovered in Dunhuang. 8th century

[22] Watson, 1968, pp. 57-58

[23] Watson, 1968, pp. 205-206

[24] Source: Zhuangzi