Hans van Rappard

12 ― From: Rappard, H. van (2009). Walking Two Roads ― Accord and Separation In Chinese and Western Thought. Amsterdam: VU University Press. Chapter 5, pp. 137-144.

Enriched edition with illustrations and with the author’s permission.

part 1 – part 2 – part 3 – part 4 – part 5 – part 6 – part 7 – part 8 – part 9 – part 10 – part 11 – part 12 – part 13 – part 14 – part 15 – part 16 – part 17

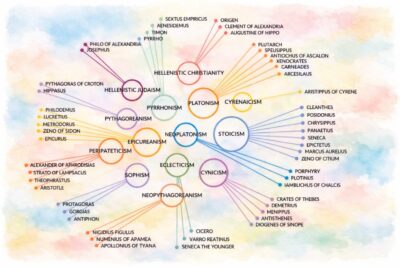

Hellenistic period

Pierre Hadot[1] has argued that Greek philosophy during the so-called Hellenistic period amounted to a ‘way of life’.

The term Hellenism designates a long historical period, which according to some authors covers Greek history from the days of Alexander the Great, who assumed the Macedonian throne in 336 BCE to the beginning of the Roman empire when Octavian received the title of Augustus in 27 CE.

Other scholars propose different dates but this should not bother us because many so-called Hellenistic philosophers taught during the era of Roman hegemony and the work of Roman Stoics as Seneca, Epictetus, and emperor Marcus Aurelius is in any case much better known than that of the Greek founders of the school. Thus, for our purposes Hellenism will span the 500 years between the end of the fourth century BCE and the end of the second century CE.

The Hellenistic schools all conceived of philosophy as a way of addressing the problems of human life, Martha Nussbaum informs us.[2] The philosopher was likened to a physician who could heal the more fundamental kinds of suffering and hence did not only practise philosophy as an intellectual pursuit.

Rather, the philosophers focused their attention on such problems as the fear of death, love and sexuality, anger and aggression, and they confronted them with a keen eye for the vicissitudes and difficulties of human life and for what is needed to allay its problems. Yet, they were very much philosophers, dedicated as they were to careful argumentation and the explicitness and rigor that has traditionally characterised philosophy in the West.

While Nussbaum thus sees Hellenistic philosophy as a kind of therapy, more specifically a ‘therapy of desire’ which is the title of one of her books, Hadot goes a step further by understanding it as a quest for wisdom and self-transformation.

When he first proposed this view it meant a new way of interpreting ancient philosophy. Hadot has maintained that at least since Socrates (469-399 BCE) Greek philosophy has aimed at transforming souls.

Socratic and Platonic dialogues

He might have mentioned Pythagoras (ca 570-ca 495 BCE) and Heradites (ca 540-ca 480 BCE), who also aimed at spiritual transformation but this starting point explains Hadot’s stress on philosophy as dialogue. The point is that Socratic dialogue may be called a spiritual exercise insofar as it induces one to pay attention to oneself.

Socrates’ maxim ‘know thyself’ requires a relation with oneself that, he says, constitutes the basis of all spiritual exercises. Hence, the Socratic and Platonic dialogues were never intended as theoretical and dogmatic affairs but rather as practical exercises.

The idea was not to communicate an intellectual system of knowledge but to make students change their points of view and attitudes. The written philosophical works of the period must therefore be understood from a spiritual training point of view. They echo oral training and appear to us as

“a set of exercises, intended to make one practise a method, rather than as a doctrinal exposition”.[4]

Moreover, as Nussbaum has argued, these exercises were not conceived of as purely intellectual and separated from ordinary life.

True enough, some ancient philosophers did strike this attitude but many of them were taken to task for indulging in literary style or subtleties of reasoning instead of exercising spiritually and addressing the real problems of human life.

It follows that in antiquity a philosopher was not always what we would call an academic, and not even necessarily a writer. Rather, a philosopher was a person who had willingly adopted a certain style of life, even if he had never taught or written.

An example is Diogenes of Sinope (ca 400-324 BCE), the Cynic who lived in a wine tub but statesmen like Cato can also be mentioned in this respect ― in short, every person who followed the precepts laid down by a recognised teacher, even women, qualified for the title of philosopher.

What made someone a philosopher was an existential attitude

“that required that he undergo a real conversion, in the strongest sense of the word, that he radically changes the direction of his life”.

Six schools of philosophy

All six schools of philosophy in the Hellenistic period ― Aristotelianism, Cynicism, Epicureanism, Platonism, Scepticism, and Stoicism ― presented themselves

All six schools of philosophy in the Hellenistic period ― Aristotelianism, Cynicism, Epicureanism, Platonism, Scepticism, and Stoicism ― presented themselves

“as choices of life, they demand an existential choice, and whoever adheres to one of these schools must accept this choice and this option”.[5]

Given their overall spiritual purpose, one sees why the philosophical writings of antiquity were not addressed to the general public ― they simply were not meant to be read by all and sundry but only by the members of the school represented by their authors. Moreover, in many cases a writing was directed at a particular disciple who needed encouragement or who had expressed special difficulties. In other cases a philosophical work had been adapted to the spiritual level of the students because not all the details of the system could be expected to be understood by beginners.

Thus, however systematic and theoretical they may appear to us, the ancient philosophical writings were produced to make their readers travel a spiritual path, not to teach them mere dogmas. They were intended to be learned as well as lived.

Plato and (neo-)Platonism

In the Platonic system, for instance, even mathematics was used to train the soul to raise itself from the sensible to the intelligible world. These philosophical books must therefore be studied by the contemporary reader with an idea of spiritual progress in mind.

The ancient authors often used extant authoritative texts and formulas to convey their message. These were paraphrased or quoted or even simply plagiarised but whatever he did, the author gave these materials a new meaning, which was adapted to what he had to say.

Thus, the Jewish author Philo of Alexandria (30 BCE-50 CE) used Platonic terms and phrases to comment on the Bible, while these comments were later used by Christian authors to present their doctrines. This, incidentally, is one of the ways in which Greek philosophy found its way into Christianity.

What mattered first of all was the authority and prestige of the traditional texts ― not their original meaning. For the ancient authors, the original ideas were far less important than the fact that they felt that their own views could be recognised in them. Thinking thus evolved by the incorporation of pre-existing terms and phrases, which of course received sometimes startlingly new meanings as they became integrated into systems that were quite different than their parental homes.

The practice of self-cultivation

In the following pages the practice of self-cultivation as conceived by the Stoics and Epicureans will be examined. In some respects their views will seem rather similar to what their Chinese counterparts had to say about the following of the Way, which ― since in the West as well as in the East the aim was human transformation ― is perhaps less surprising than might appear at first sight.

However, one point of difference leaps immediately to the eye: in ancient Greece a rational conception of the cosmos occupied centre stage, which was of course a far cry from the Chinese perspective on the universe. But, a twenty first century human is bound to ask, what on earth could a rational conception of the universe entail? To answer this question we will have to digress briefly to the physics of Stoics and Epicureans.

The Stoics

The fundamental principle of Stoic physics holds that all things in the cosmos operate in accord with the universal reason, or logos. This rational principle is sometimes called ‘God’ but it is not a Homeric god living on the Olympus that is meant, let alone a precursor of the God of Christianity but rather a rational, organising principle.

According to the Stoics, the cosmos is governed by the logos, actively organising a physical substance called pneuma, which constitutes the second, passive principle.

Pneuma permeates everything in the cosmos. At the lowest organisational level of hexis objects have physical properties, while at the next level of physis plants are capable of growth. Animals posses the yet higher degree of psyche, and at the top of the scale humans manifest reason (nous). As contrasted to universal reason (logos) the nous operates in individuals. One sees that the levels of reality are differentiated according to their complexity of organisation; the Stoic cosmos was an organic whole in which everything exists within everything else.[7]

The Epicureans

Epicurean physics is entirely different. It is atomistic and seems to have been taken from Democritus, the fifth century BCE philosopher who was the first to conceive of atoms.

The Epicurean system is summarised in fourteen maxims in Lucretius’ poem On the nature of the universe, from which we derive the following.

There is no divine creation, only natural causes bring things about; atoms vary in shape and size; and life and sensation take place in physical objects in an appropriate way. Further, the only properties of atoms are size, shape, and motion; all other properties can only be possessed by compounds of atoms. Thus, the mind is a compound of atoms. The atoms cannot change; the changes that we perceive result from the recombination of atoms into new compounds. Moreover, atoms are self-propelled and can swerve at random times and by random amounts. Although mental operations are also atomic collisions, the introduction of the last principle allows Epicurean philosophy to steer clear of determinism and find room for the freedom of will.[8]

Physics had an ethical dimension

We return to the Stoic concept of reason. Generally speaking, human reason aims at coherence, just as one who is engaged in rational argument will avoid contradicting himself. Along similar lines the Stoics ascribed rationality to nature and saw the ‘will for coherence’ as a fundamental law in physics[9].

This may sound peculiar but it should be realised that the current meaning of the word physics was not coined until the sixteenth century to meet the demands of modern science. To the Stoics and other schools, what we now think of as scientific knowledge was subservient to philosophy as a way of life, that is, physics was not pursued for its own sake but had an ethical dimension. They would be little inclined to accept that there is order and thus rationality in the world, but not in human beings.

“To a reasoning being, an act that accords with nature is an act that accords with reason”,

Marcus Aurelius observed in his Meditations.[10]

Everything in the world is related to everything else

In the Stoic view human reason (nous) rests on the universal reason (logos) of which we are but a minuscule part and hence, living in conformity with reason means living in conformity with nature, or the universal law. Thus it can be understood that from the first moment of their existence human beings were said to be naturally in tune with themselves and that for the Stoics the cosmos is a

“single living being which is likewise in tune with itself and self-coherent. Just as within a systematic, organised unity, everything in the world is related to everything else, all is in all, and everything needs everything else”.[11]

More or less similar to what was seen in Plato, to the Stoics moral action, virtue, and wisdom had a cosmic dimension: ultimately all come down to the harmonisation of the reason which lives within all of us (nous) with the reason which guides and orders the cosmos and makes up fate (logos).

To the Stoics, in other words, morality is a matter of harmony between personal and universal reason. Their telos or goal of life is, living consistently with nature ― that is, in accordance both with one’s own nature and with that of the whole:

“… Now this itself is the virtue of the happy person and a smooth flow of life whenever everything is done according to the harmony of the spirit in each person with the will of [Zeus, who is] the administrator of the whole … The reason why the perfection of one’s reason is also a state of agreement with (universal) reason … is that included in [this perfection]is a process in which one comes to understand the nature of the whole universe”.[13]

In spite of the differences between the two schools a similar view is found in Epicureanism. In both schools the adherents are expected to develop a ‘cosmic consciousness’, that is, to become conscious of forming part of the cosmos. Whereas the average human being is out of tune with the world and can see it only as a means to the satisfaction of his desires, the philosopher keeps the cosmic whole in mind and so may perceive the world in its own right.

Development of cosmic consciousness

Of course, reason was also of paramount importance in the spiritual exercises that had to be carried out by the aspiring philosophers. Indeed, the transformation aimed at by the Stoics and Epicureans entailed a way well-paved with reason. Small wonder then, that the Hellenistic ways involved a measure of rationality that is incomparably larger than what can be expected of the non-philosophers, toiling in the world without the merest understanding of the scheme of things. But the philosophers were not geared to rationality in the common-sense meaning of the word; quite the other way round.

An abyss between philosophical and ordinary life

Hadot noted a rupture, an abyss even, between their way and ordinary life, which was strongly felt by the men in the street. Comic and satiric authors tended to portray the philosophers as bizarre, if not outright dangerous characters and this was of course not mitigated by the large numbers of charlatans who passed themselves off as philosophers. Lawyers also considered them a race apart and saw no need for the authorities to be concerned with them because they professed to despise money. A contemporary regulation on salaries and compensations noted that if a philosopher is caught haggling over money this demonstrates that he is no real philosopher.

Or take the Epicureans, who led a frugal life and ― just imagine ― practised equality with the women in their circles, including courtesans. Nor did the behaviour of the Stoics show much rationality or even plain common sense. Many administered the provinces of the Roman empire with sovereign disinterestedness and were among the few to take seriously the laws against excess.

In the Platonic dialogues Socrates was already called atopos, that is, unclassifiable. What made him thus in the eyes of the general public was the fact that he was literally a philo sopher, someone who is in love with wisdom. For wisdom was not considered a human state; rather, it was a mode of perfection foreign to the world so that those who loved it could not but be strangers.

Naturally, every school produced its own depiction of the state of perfection in the person of the sage but all agreed that this ideal is virtually impossible to achieve. Some schools held that actually there had never been a truly wise man, while others thought that there might have been at most one or two of them, such as Epicures, who was considered a god among men. Yet other schools believed that while it was possible to attain to perfection this could only be accomplished during rare and fleeting moments.

Ideal of wisdom: living in utopia

Thus, the philosopher found himself in a paradoxical position: neither could he become a sage nor could he remain an ordinary human being. This is so because on the one hand, he knows that the natural state of mankind should be wisdom since this is after all the vision of things as they are in the light of reason, which requires a way of life corresponding to this vision. But on the other hand, he knows only too well that the so-called natural state of wisdom is actually an ideal which is practically inaccessible to him. In other words, the philosopher must live in a world which he has come to regard as strange but which regards him too as strange. Ironically then, aspiring to what for him must be utopia, the philosopher himself becomes atopos.

The result is a conflict between the philosophical life that should be lived, and the conventional life that cannot but be lived. This conflict is irresolvable but there existed various coping strategies.

For instance, Diogenes the Cynic totally refused the world of social conventions, which he eyed contemptuously from his tub. The Sceptics on the other hand, had no difficulty in accepting the conventional world but went to great lengths to keep their inner peace. And while the Epicureans tried to live in conformity with their ideal of wisdom in circumstances that were especially created for this aim, the Stoics strove to live a philosophical life in both the everyday world and the public domain. But for all of them, being a philosopher required an effort to live according to the norm of wisdom. Thus, every Hellenistic school represented a form of life that was determined by this ideal and knew an array of exercises that had been designed to further progress on the never-ending path toward this elusive state. All these exercises pertained to reason.

Generally, Hadot says by way of summary,

“they consist, above all, of self-control and meditation. Self-control is fundamentally being attentive to oneself: an unceasing vigilance for the Stoics, the renunciation of unnecessary desires for the Epicureans. It always involves an effort of will, thus faith in moral freedom and the possibility of self-improvement; an acute moral consciousness honed by spiritual direction and the practise of examining one’s consciousness; and lastly, the kind of practical exercises described with such remarkable precision particularly by [the Stoic]Plutarch: controlling one’s anger, curiosity, speech, or love of riches, beginning by working on what is easiest in order gradually to acquire a firm and stable character”.[15]

We can now turn to a more detailed treatment of the Stoics and the Epicureans. Of course, it is their view of philosophy as a way of life in particular that will receive our attention. The quotation above pertains to both schools and serves well as a concise preview.

In the preceding chapters we have come across enough material on the Chinese tradition to be struck by terms as self-control, effort of will, and moral freedom on the one hand, and meditation, self-improvement, and controlling one’s anger, etc. on the other hand. While the latter may seem more or less similar, or at least sitting well with what was found in the three Chinese schools that we have gone into, the former are likely to strike one as being very much at odds with it.

- Bett, R. (2006). Stoic ethics. In M.L. Gill & P. Pellegrin (Eds.). A companion to ancient philosophy (pp. 530-548). Oxford: Blackwell.

- Green, C.D. & Groff, P.R. (2003). Early psychological thought: Ancient accounts of mind and soul. Westport (CT): Praeger.

- Hadot, P. (1995). Philosophy as a way of life ― Spiritual exercises from Socrates to Foucault. (A.I. Davidson, ed.; Chase, Transl). Oxford: Blackwell.

- Hadot, P. (2002). What is ancient philosophy? (M. Chase, Transl). Cambridge (MA): Harvard U.P.

- James, W. (1890/1950). The principles of psychology, Vol. I. New York. Dover Publ.

- Long, A.A & Sedley, D.N. (1987). The Hellenistic philosophers, Vol. I. Cambridge: Cambridge U.P.

- Nussbaum, M.C. (1994). The therapy of desire: Theory and practice in Hellenistic ethics. Princeton: Princeton U.P.

- Staniforth, M. (Transl). (2004). Marcus Aurelius: Meditations. London: Penguin Books.

Notes

[1] Read more about Pierre Hadot

[2] Nussbaum, 1994, pp. 3-4

[3] ‘Gnothi Seauton’ was said to be inscribed on the Temple of Apollo at Delphi: “know thyself”.

[4] Hadot, 1995, p. 21

[5] Hadot, 1995, p. 30

[6] Source in the Public Domain of a drawing of Philo of Alexandria by André Thevet,French explorer, journalist, writer, cosmographer, geographer and historian (1502 (?)-1592): “Les vrais pourtraits et vies des hommes illustres grecz, latins et payens” (1584). Source: https://archive.org/details/lesvraispourtrai01thev

[7] Green & Groff, 2003, pp. 100-102

[8] Green & Groff, 2003, pp. 111-112

[9] Read more on the Greek concept of Logos

[10] Staniforth, 2004, p. 77

[11] Hadot, 2002, p. 129

[12] Source in the Public Domain of a mosaic of Plato’s Academy mosaic (from Pompeii), Roman mosaic of the 1st century BCE from Pompeii, now at the Museo Nazionale Archeologico, Naples.

From the House of T. Siminius Stephanus, Pompeii. Source/Photographer Own work Jebulon

[13] Bett, 2006, pp. 534-535

[14] Source in the Public Domain of an oil painting (1860) of Diogenes by Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824–1904): “The Greek philosopher Diogenes (404-323 BC) is seated in his abode, the earthenware tub, in the Metroon, Athens, lighting the lamp in daylight with which he was to search for an honest man. His companions were dogs that also served as emblems of his “Cynic” (Greek: “kynikos,” dog-like) philosophy, which emphasized an austere existence. Three years after this painting was first exhibited, Gerome was appointed a professor of painting at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts where he would instruct many students, both French and foreign.”

Walters Museum, Baltimore, US.

[15] Hadot, 1995, p. 59