Hans van Rappard

8 ― From: Rappard, H. van (2009). Walking Two Roads ― Accord and Separation In Chinese and Western Thought. Amsterdam: VU University Press. Chapter 3, pp. 86-102.

Enriched edition with illustrations and with the author’s permission.

part 1 – part 2 – part 3 – part 4 – part 5 – part 6 – part 7 – part 8 – part 9 – part 10 – part 11 – part 12 – part 13 – part 14 – part 15 – part 16 – part 17

It might be anticipated that in China the relation between human beings and the world was conceived along different lines than in our part of the globe. Going into Chinese poetry the concepts of xing and xiang were met which, often combined, entail that a merger is established between man and world in an emotional flux.

Xing-xiang intermediates between world and man ― and emphatically in that order.

But in Stern the person-world relation is conceived in a different direction. Admittedly overstating things for the sake of exposition, whereas in Chinese poetry the relation is world à man, in Stern it is man à world. One recalls that in the Western world the relation has not always been conceived along such lines and that the ancient Greeks deemed world and cosmos rather more important than what we now think of as the human self.

But the Chinese view, especially in its Confucian form has remained essentially the same for some twenty five hundred years and so could deeply affect the cultural tradition. Thus, strange as it may seem, for present purposes the ancient Confucian view can in many ways still be pitted against the modern Western view of the self.

A fundamental feature of thinking as it developed in Greece that never occurred to the Chinese is the notion of some kind or other of ’higher’ world. Although they did to some extent speculate about the nether world of the dead, their thinking remained pretty much rooted in the reality of our everyday world.

Thus, many authors characterise Chinese thinking as thoroughly this-worldly. A typical saying in the Confucian Analects or Lunyu[1], which unless otherwise stated will be quoted from Arthur Waley’s translation, has it that Confucius, asked about the meaning of death answered,

“not yet understanding life, how can you understand death?” (Book XI, ii).

Deeply concerned with the problems of government

Our journey into Chinese philosophy will start with the observation that traditionally it is deeply concerned with the problems of government. There are good reasons for this because when the first schools came into existence, roughly at same time as in Greece (5th-3rd centuries BCE), China was in great turmoil.

Towards the end of the Spring and Autumn period (722-481 BCE) the feudal society of the Zhou (Chou) dynasty (1122-221 BCE) was gradually broken up by a number of newly emerged states, giving rise to the Warring States Period (403-221 BCE) which came to an end when China was united for the first time by the harsh and short-lived Qin dynasty (221-206 BCE). In the midst of the chaos and anarchy caused by long years of war the earliest Chinese philosophers naturally addressed the question of how these problems could be solved and harmony restored.

Thus, Chinese philosophy can be said to have been born of political and social problems, which might to some extent explain why it did not develop into a more theoretical affair. An important ingredient of the solutions to the problem of government consisted of a highly idealised view of the past. Significantly, when Confucius speaks of learning what he means is acceptance of traditional knowledge handed down from generation to generation.[2]

Shang dynasty: the ideal society of the distant past

The ideal society was thought to have actually existed long ago in the hazy beginnings of the Zhou dynasty or yet farther back in the more or less mythical Shang dynasty (1766-1123 BCE). History tended therefore to be seen as a retrograde process, while the proposed governmental solutions often entailed a return to the ideal society of the distant past.

But we must be careful when thinking of Chinese philosophy as ‘political’ philosophy because this modern Western term should be taken with a good grain of salt when used in an East Asian context. It is inextricably linked to what we call ethics, anthropology, and philosophy of history even if these have never existed as independent pursuits in the East. Along with the political and practical bent of Chinese philosophical thinking its integral nature comes strikingly to the fore in its spiritual dimension, which, incidentally, somewhat mitigates its alleged this-worldly nature.

But then, as is the case with so many other Western distinctions, the this/other-world one had better be avoided because it is not really applicable. In any case, with regard to what follows it is useful to keep in mind that the solutions to political and societal transformation conceived by traditional Chinese philosophy have almost invariably also stressed the need for personal transformation.

The Way (Dao) has both social and individual ramifications and in this case too, the line separating them is blurred. Moreover, and this would seem to complete the holistic picture of philosophical thinking in China, since in the various ways towards transformation a harmonious relation between nature and human beings is deemed essential a philosophical view of nature often forms part of the package too.

Confucianism, Daoism and later on Buddhism determine the course of Chinese philosophy

Although many schools have been developed, Confucianism and Daoism between them, along with the proto-typical philosophy of the Yijing (chapter one) have virtually determined the course of Chinese philosophy down to this day. Both schools have gone through a long development during which a third stream ― not originally Chinese ― has also played a significant role: Buddhism.

Although Confucianism and Daoism originated separately and independently and at first sight seem very different, they nevertheless have a number of points in common (below). In this regard it must be noted that although many books, including the present one, speak for the sake of convenience of ’schools’, this is actually a gross simplification because Confucianism and Daoism (and Buddhism for that matter) constitute no schools at all, not even vaguely delineated ones. They are more like widely branched off streams forming intricate river systems.

Over the centuries a number of Confucian and Daoist movements emerged in whose development both parental forms plus Buddhism had an important role. Even if they have at various times been at odds with each other, their mutual influence serves as an indication that Confucianism, Daoism, and Buddhism were generally not taken as offering fundamentally different perspectives. Their founders were often portrayed together and their statues could, and perhaps may nowadays again be found on many temple altars.

In the next paper on the Chinese ways of self-cultivation further indications will be found of the common ground between these Chinese schools.

Practice of the Mean (Zhongyong)

Here the point will be addressed by going into the Practice of the Mean (Zhongyong), henceforth referred to as the Mean.

Along with the Lunyu, the Mengzi or Mencius, and the Great Learning or Da Xue, the Mean makes up the Four Books, edited by the Neo-Confucian Zhu Xi (1130-1200), a Confucian scholar who drafted the Chinese state doctrine and the examinations that until 1905 had to be passed by aspiring civil servants.

Although the Mean was originally not a book but a chapter of the Liji (Book of Rites)[4] that probably dates from the first century BCE, it is traditionally assumed to have been recorded or perhaps composed by a grandson of Confucius in the fifth century BCE.

The book has exerted an enormous influence on Confucianism and Chinese thinking at large, which began already during the Han dynasty (206 BCE-220 CE), while it was mobilised during the Song dynasty (960-1229) against Daoism and Buddhism by the Confucians who felt the need to unpack the spiritual implications of the Master’s message.

During the next thousand years of Chinese history the slight volume of the Mean has formed part of the core of its cultural heritage. It is among the canonical books that constituted the primary curriculum for the civil service examinations, formed the basis of an extensive body of learned commentaries, and finally, but certainly not least, provided the focus as well as the terms and topics of many later Confucian writings.

Chinese learning

Andrew Plaks[5] calls the Mean, together with the Great Learning, the central ground of orientation and the ‘home-port’ within the vast ocean of traditional Chinese learning. Indeed, Chinese learning ― not just Confucian learning. The author of the Mean must have been well aware of the writings of other schools because in its investigation of the deeper layers of human life it echoes the Daoist worldview and has exerted a far reaching influence on the

“mutual supplementation and mutual interpretation of Confucian, Taoist, and Buddhist spiritual currents.”[6]

The passages from the Mean, printed below, have been taken from Andrew Plaks’s liberally paraphrasing translation. The first chapter, quoted in full, contains what Zhu Xi called, its canonical core, presenting a summary of its central points.

“By the term ‘nature’ we speak of that which is imparted by the ordinance of Heaven;

by ‘the Way’ we mean that path which is in conformance with the intrinsic nature of man and things;

and by ‘moral instruction’ we refer to the process of cultivating man’s proper way in the world.

What we take to be ‘the Way’ does not admit of the slightest degree of separation therefrom, even for an instant. For that which does admit of such separation is thereby disqualified from being the true Way.

Given this understanding, the man of noble character exercises utmost restraint and vigilance towards that which is inaccessible to his own vision,

and he regards with fear and trembling that which is beyond the reach of his own hearing.”

For, ultimately, nothing is more visible than what appears to be hidden, and nothing is more manifest than matters of imperceptible subtlety. For this reason, the man of noble character pays great heed to the core of his own individuality.

It is only to that state of latency within which the four archetypal markers of human experience: joy, wrath, grief, and delight have not yet emerged into concrete manifestation that we may properly attribute the perfectly centred balance of the ‘mean’[7]. Once these markers have emerged into reality, in such manner that they remain in balance and in due proportion, we may then speak of them as being in state of ‘harmony’. What is here termed the ‘mean’ constitutes the all-inclusive ground of being of the universe as a cosmic whole, whereas the term ‘harmony’ refers to the unimpeded path of fullest attainment in the world of human experience.

Balance and harmony

When the attributes of both the balanced mean and harmony are realized to their fullest extent, the Heaven and Earth assume on this ground their proper cosmic positions and the regenerative processes of all the myriad creatures are sustained therein.

Not only did Zhu Xi edit the Mean but he also produced extensive comments on it With regard to the first chapter he wrote,

“it shows clearly that the origin of the Way is traced to Heaven and is unchangeable, while its concrete substance is complete in ourselves and may not be departed from.”[6]

Thus, our inherent human nature is no different than cosmic nature. Moreover, there being no inherent difference between them and the Way, whose origin is traced to Heaven (nature) is present in us in its entirety and may not be departed from. Yet, human beings do depart from the Way and this is putting it mildly because actually no one, with the possible exception of an occasional sage, is capable of fully obeying the Mean. Therefore, towards the end of chapter twenty of the Mean we read,

“A perfect state of integral wholeness can only be attributed to the Way of Heaven; the process of making oneself whole is, however, within the province of the Way of Man. ‘Integral wholeness’ means a state of centred balance requiring no striving, complete attainment requiring no mental effort. To strike the mean with absolute effortlessness is the mark of none but those of perfect cultivation. The process of ‘making oneself whole’, by contrast, requires choosing the good and holding fast to it with all one’s strength.”

The Way of man is defined here as ‘making oneself whole’, Plaks explains[9], which is reflected in the description of the state of centred balance as ‘attainment requiring no mental effort’. In the next line the character denoting the mean is used in the sense of what it graphically depicts, to hit the centre of a target ― in this case the centre of the Way ― while in the last line ‘choosing the good and holding fast to it’ should be read in light of the definition of the mean as a variable point of equilibrium or balance. Given Zhu Xi’s definition of the mean as

“what is not one-sided” or Legge’s “being without inclination to either side”,[10]

the Way of man appears to come down to avoiding one-sidedness or inclination to either side. In the remainder of the present chapter and in chapter four I will demonstrate that the counsel ‘don’t be one-sided’ or ‘don’t incline’ virtually summarise the Chinese Way of man.

Aristotle’s concept of the golden mean

The Chinese mean has a Western counterpart. It is found in Aristotle’s concept of the golden mean. The two means have in common that both are thought to be well-nigh impossible for human beings to keep to but in every other respect they are different. Aristotle’s mean (meson) indicates a middle position between two points, generally speaking excess and deficiency. For instance, between recklessness and fear lies courage.

To distinguish clearly between the Chinese and the Greek mean, the former will be referred to as ‘mean’, the latter as ‘middle’. In contradistinction to the mean the middle is determined by its extremes; fear may be thought of as deficient courage, while recklessness is an excess of it. It is important to understand that because of its dependence on its extremes the Greek middle is relatively static and lacking in freedom. Standing at the middle position between any two extremes entails that one is relegated to a ‘halved life’.

Chinese: the mean is not static at all

The Chinese counterpart, however, cannot be called static at all. Keeping to the mean is not the same as clinging to it, Jullien observes, playing on the ambiguous meaning of the French verb tenir. The difference is that by ‘keeping’ rather than ‘clinging’ to the mean, that is, by simply avoiding to incline to one of two sides rather than grimly holding on to the middle position, one remains open to both. The mean, after all, is a matter of one side and the other.

This should have a familiar ring because a similar stance was found in the Yijing. It will be encountered again in Daoism and Buddhism. But avoiding to incline has yet another effect. It ensures that no wilful intentions arise in the heart-mind. Not clinging to either side, one does not get locked in but remains free to shift from one side to the other.

While the Greek seeking the golden middle is caught between extremes so to speak, the Chinese may take whatever course of action is demanded by the situation he finds himself in, which, however, may change any moment and require a different or even opposite action.

In balance and in due proportion

It is important to see that in contradistinction to the Greek middle the Chinese mean is not determined by the nature of the action embarked on but by its quality. Keeping to the mean or, more feasible for human beings, keeping the movements of the heart ‘in balance and in due proportion’, as the first chapter of the Mean phrased it, demands that one acts wholeheartedly, that is, pre-intentionally. Put schematically then, the difference between the Western and Eastern views is that the Greek middle is a point between two extremes, while the Chinese mean is the pre-intentional ‘point’ from which they spring.[12]

With the quotation from chapter twenty of the Mean and Plaks’s comment we have actually dealt already with Zhu Xi’s next observation that the first chapter

“speaks of the essentials of preserving, nourishing, and examining the mind”,

which are the mental operations required to make oneself whole to some extent and thus achieve a measure of harmony. Even if achieving harmony is well-nigh impossible for human beings, the Way of man demands all the restraint and vigilance one is able to muster, together with an attitude, which, in view of the fear and trembling vis-a-vis what is beyond the senses, can best be described as obedience.

Zhu Xi’s third observation points out that the first chapter also speaks of

“the meritorious achievements and transforming influence of the sage and the spirit of man in their highest degree.”

The final chapter of the Mean describes these achievements succinctly as

“the man of noble character behaves with integrity [often translated as sincerity]and respect, and all the world is at peace.”

Peace

And peace, we recall, was a central problem in ancient Chinese philosophy. The following parts from chapter twenty deal extensively with the transforming influence of the self-cultivated ruler on the fabric of society, which, incidentally, consisted largely of the family system.

“Just as the ‘Way of the Earth’ infuses a quickening vitality into trees, so, too, the ‘Way of Man’ provides the vital force of ruler-ship. In this sense, the art of rulership is likened to a quick-growing reed.

From this we conclude that the proper conduct of government rests upon human capacity;

the ground for selecting human capacity lies in the ruler’s own individual character;

the cultivation of one’s own individual character proceeds on the basis of the Way;

and the cultivation of the Way is grounded in the virtue of human kindness …”

The greatest expression of human kindness is in the treatment of one’s kin with the proper degree of affection, just as the greatest manifestation of rectitude is in the honouring of the worthy. The maintenance of proper gradations in the affectionate treatment of one’s kin and the observance of appropriate ranking in the honouring of the worthy constitute the ground from which the entire system of ritual propriety springs. It follows that the man of noble character must never cease to cultivate himself. Still in chapter twenty we read,

“The Master has stated:

‘Love of learning is not far removed from wisdom; Rigorous practice brings one close to human kindness; and a sense of shame is nearly tantamount to courage.’

He who fully grasps these three virtues will understand thereby the essential grounding of self-cultivation;

He who grasps the grounding of self-cultivation will understand thereby the basis for instilling order among men.

He who grasps the basis for ruling men will thereby understand the ground for establishing order in his family, in his kingdom and in the entire world.”

One is likely to wonder what all this might entail with regard to the Chinese view of man. But one point at least has become clear from the quoted parts of the Mean: there is no gap, no duality between cosmic nature and human nature.[13]

As we will see below, this is only the first of several dualities which have never been conceived of in Chinese thinking, whereas they are rampant in the West. And undoubtedly another striking point is the enormous weight given to self-cultivation and learning. Looked at from that angle, the Chinese person emerges as a very dynamic being.

Indeed, the Confucian Analects (Lunyu) abound with exhortations to learn without pause. In Book II, 4 the Master observed about his own career,

“At fifteen I set my heart upon learning. At thirty, I had planted my feet firm upon the ground. At forty, I no longer suffered from perplexities. At fifty, I knew what were the biddings of Heaven. At sixty, I heard them with docile ear. At seventy, I could follow the dictates of my own heart; for what I desired no longer overstepped the boundaries of right.”

Given the Confucian stress on learning it must not be overlooked that this entails much more than the mere acquisition of instrumental knowledge and skills. It rather constituted a full-blown way of self-cultivation. Learning the lessons contained in poetry and even more so the mastering of the ancient rituals was a deeply edifying affair. To Confucius, learning the rituals did not just aim at correct performance but

“shaped the character of those who practiced them, expressed and further refined the virtue [de] of those who knew them well, and influenced those who participated in or observed a given ceremony.”[14]

As learned from the Mean, one of the bases of Confucianism is found in the natural order of things in human society, that is, family, kinship, clan, state, and world. All these are considered natural to society; they constitute the fundamental human relations and also provide the resources for human self-cultivation. Everything to do with the self and its ‘realisation’ has received rather poignant individualistic overtones in our part of the world but these are completely absent in Confucianism. According to its view of man the transformability of the human condition and even its perfectibility (a word that did not rise to prominence in the West until the eighteenth century Enlightenment) have over many centuries been remarkably salient features.

Confucian self-cultivation

The goal of Confucian self-cultivation, the man of noble character (also translated as gentleman or superior man) is achieved by the embodiment (ti) of ren, yi, li, and zhi.

The first of these characteristics, ren (humaneness, benevolence) involves an affective concern for all people, although in different degrees depending on one’s social relation to them. This ‘measured ren’ was severely criticised by Daoism. The second one, yi (righteousness, propriety) is a commitment to adhere to certain ethical standards. The third characteristic, li (the observance of rites) commits the Confucian to follow the traditional rules governing the interaction between people, while zhi (wisdom) involves the ability to assess what is proper in a way that is sensitive to particular circumstances. The total commitment to the ethical life advocated by Confucianism is expressed by cheng.

This is an important concept in the Mean. Cheng is usually translated as truthfulness or sincerity but Plaks rendered it as integral wholeness or the integrity of the inner self. It refers to a state in which there are no discrepancies between one’s inner condition and outer behaviour or within the heart itself.

“Not a single thought or inclination is incongruent with [ren, li, yi, and zhi]; there is nothing that could cause the slightest reluctance or hesitation about acting properly.”[15]

Cheng is the basis of government because self-cultivation does not only affect the person but can also transform others. The goal of government is to transform the character of the people, which is to be achieved by first cultivating oneself and then letting the power of one’s transformed character take effect. In the Analects (Bk. II, i) Confucius says,

“He who rules by moral force (de) is like the pole-star, which remains in its place while all the lesser stars do homage to it.”

Thus, while the basis for order is to be laid by cultivating or ordering oneself, a failure to transform others is indicative of a failure in self-cultivation. It is imperative for the Confucian to keep in mind that self-cultivation is not to be engaged in for the advancement of one’s personal interests although this would certainly be possible. As the Master warned,

“The gentleman can influence those who are above him; the small man can only influence those who are below him” (Analects Bk. XIV, 24).

Clearly, the ‘self of Confucian self-cultivation is not individualistic in the modern Western sense of the word. Rather, the emphasis is on a self that is inextricably intertwined with human society.

“Confucians share an emphasis on self-cultivation as something to which one should be devoted for a life-time, with the inner goal of improving oneself rather than for the external advantages that it brings. There is also general agreement on the goal of self-cultivation ― which involves a complete transformation of the self and a total commitment to the ethical life … and on the importance of self-cultivation to the political order.”[16]

We are still left with the question as to how the Confucian self has to be understood in this context. Just how is the relation conceived between the self and the human world? The first thing to realise is that there was

“less emphasis in early Confucian thought on an interior or distinctly ‘spiritual’ life than we might expect, either from later Chinese traditions or from Western stereotypes of the ‘mysterious East’.”[17]

Oneself is in reciprocal relation

Rather, what one is supposed to learn from the Four Books is to see oneself not in isolation but in relation. Confucianism understands the human self as a self-in-relation, as irreducibly interpersonal. And this rules out another Western dichotomy ― next to the gap between nature and man the cherished split between society and individual vanishes. In Chinese thinking society and its members are conceived of as mutually dependent or, put differently, both are interdependent. The relation may thus be represented as human world ßà human being. Attributing selflessness as an ideal to the Chinese tradition would entail that we

“sneak in both the public/ private and the individual/ society distinctions by the back door.”[18]

But these distinctions never had a place in Chinese thought. From the beginning some twenty five hundred years ago, Confucianism has thought in terms of reciprocal relations, that is, of benefiting and being benefited in a human world of loyalties and obligations. Confucianism allowed ample room for the person, although, when compared with Stern’s concept[19], it would appear to be a ‘de-centred’ person and thus a far cry from his activity centre.

Admittedly, some authors view the Confucian self as a centre.[20] But what they have in mind is a centre of relationships and as such this centre is emphatically not the more or less isolated starting point and control centre of one’s transactions with the world but rather the continuously shifting locus in a web of mutual relationships. For Confucius, Rosemont points out,

“I am not a free, autonomous, individual self; rather am I more foundationally a son, husband, father, friend, teacher, student, neighbour, colleague, and so forth … Other persons are not merely accidental or incidental to my achieving personhood and struggling for goodness, they are essential therefore; indeed, they confer personhood on me.”[21]

In other words, the position of the Confucian person vis- à-vis Western points of view as individualism and collectivism holds that as a locus of relationships a person, as different from an individual, comes into being by interacting with its natural human environment, that is, family, community, and state. Communicating in an ever more inclusive web of relationships the Confucian person gradually embodies increasingly wider circles of interaction. Confucianism, along with most other Chinese schools of thought denies that the human world is made up of independent individuals. Their social and ethical thinking

“begins with relationships and roles in relationships. Confucian thinkers stress reciprocal responsibilities rather than … rights and duties.”[22]

Seen in this light, it is not surprising that until the mid-nineteenth century the Chinese knew no word for ‘rights’ in the sense of human rights and even today have not much warmed to this notion. As opposed to collectivists, Confucians maintain the central place of the person but, and this bears repeating, as intimately related with other persons. It follows that self-cultivation does not entail a withdrawal from the world. After all, it was learned from the Mean that human nature is imparted from heaven and thus shares the reality that underlies the ten thousand things.

“To actualize this underlying reality, therefore, is not to transcend reality but to work through it.”[23]

Indeed, the Confucian gentleman needs no ‘other’ world, spiritual or otherwise to take refuge to. As chapter twenty-two of the Mean says,

“He who can partake in the transformative and generative processes of Heaven and Earth can stand, by virtue of this capacity, as a third term between them in the cosmic continuum.”

The significance of the body

The relation between cosmos and human nature constitutes one of the most central aspects of the Chinese view of man vis-à-vis the modern Western notion, but there are other differences too that have to be mentioned. The first of these concerns the significance of the human body.

In the Chinese tradition the human physical nature has always been fully recognised. This is testified by the importance accorded already in ancient times to rhythmic bodily exercises and yogic breathing techniques. But not only were bodily exercises highly valued as contributing to the process of self-cultivation, the conception of traditional Chinese medicine is geared to healing in the broad sense of maintaining and restoring man’s vital energy (qi) rather than curing symptoms. Thus, the idea of the wholeness of the body, often understood as allowing the vital energy to flow smoothly, is laden with implications pertaining to traditional medicine as well as self-cultivation. As demonstrated by the current use in the West of meditation practices for the sake of relaxation and other kinds of wellness both may indeed be difficult to keep apart.

In China the human body is seen as the point of departure for self-cultivation because it houses or ‘in-bodies’ the heart-mind, which adds an important dimension to its esteem. One recalls that the Chinese notion of the heart-mind involves both the affective and cognitive function of the mind. But it is the affective function that is privileged as the “defining characteristic of true humanity.” Hence,

“Confucians underscore feeling as the basis for knowing, willing, and judging. Human beings are therefore defined primarily by their sensitivity and only secondarily by their rationality, volition, or intelligence.”[24]

Confucius said,

“As for Goodness ― you yourself desire rank and standing; then help others to get rank and standing. You want to turn your own merits to account; then help others to turn theirs to account ― in fact, the ability to take one’s own feelings as a guide ― that is the sort of thing that lies in the direction of Goodness” (Analects Bk. VI, 28).[25]

The importance of the body in Chinese thinking comes also to the fore in the word ti, meaning body or embodiment. Ti is one of the earliest and most important concepts in Chinese philosophy. The basic meaning of the word is the human body as a living, organic system. By abstraction this may be extended to anything that has a definite organisation. Used as a verb however, ti may also refer to the intimate experience of one’s body as a living whole. This is called, ‘coming to know by intimate, personal experience’. There is no end to what can thus be experienced. Not only can we intimately experience our own life but also life in general and even the Dao, and this is possible

“because, as humans, we have the ability to experience intimately both internal and external reality on many levels. However, to develop this ability ― to make it active and productive ― we need to cultivate ourselves.”[26]

The verb ti may also mean ‘to embody’, which can be understood as an extension of intimate experience because to embody something is to form ‘one body’ with it. This is

“to experience intimately the ten thousand things and to establish a continuing organic, interactive, and mutually supportive relationship with them. It implies an affective attitude of care and regard ….”[27]

But there is yet a third meaning, which is ‘to practice and implement’. In this case ti may also be understood as embodiment but now in the sense of realising embodiment. Thus, a sage must cultivate his virtue

“because virtue is not a matter of abstract understanding but of embodiment in life.” The same applies to knowledge, which can only be called genuine “in terms of actual, bodily practice.”[28]

Clearly, the Chinese did not conceive of the body as an impediment to self-cultivation as did the Greek philosophers and, under their influence, Christian theologians. Indeed, there was no reason, no possibility even for them to do so because they did not dichotomise body and mind. And this means that after the gaps between nature and human beings, and between society and individual, yet another Western dualism is found to be lacking in Chinese thinking.

Person not as an actor, as acting

The third feature of the Chinese view of man, its dynamic nature and flexibility constitutes another difference with the Western view. To return briefly to a previous example, as a pioneer of developmental psychology William Stern did of course recognise that the human person did not just fall from the sky but emerged from a long process of education, and also that it was subject to change and could to some extent be transformed. Generally speaking, there are no reasons to maintain that the malleability of man was not recognised in the Post-Enlightenment West, but more than two millennia ago Confucius had already gone a step or two further. ‘Becoming’ is not just one characteristic among others, even if an important one, but it simply defines the Confucian person. In the second section of the Great Learning (Daxue), the briefest of the Four Books it is said,

“Would that one renew oneself daily, ever newer from day to day, and new again which each passing day.”

The flexibility of the human being is taken so far that it makes one wonder if Western concepts as person and self are adequate to render the Confucian view of man. The Western self, which is the outcome of a long historical development is understood as the core of one’s being and heavily invested with thing-like overtones. Over many centuries we have come to think of self and person and the like as static entities, but such an attitude is decidedly out of step with the Chinese view.

Therefore, we had better be reluctant to speak of self and person in this connection. Rather, and this is a real departure from the Western view,

“we ought to speak of a person as acting, but not suggesting by ‘person’ this notion of an Actor who somehow embraces inwardly a moral or psychic core which is then expressed in action.”[29]

If we are prepared to understand the Confucian person in terms of activity rather than static structure, the Western dichotomy between ‘ordering centre’ (ego, self, or person) and ‘ordered mental contents’ (thoughts, desires, and so on) will be avoided and notions of a unifying mental agency might be abandoned.

In other words, what may well constitute the anchor-point of some of the most cherished Western dichotomies appears to be non-existent in Confucian thinking, and Chinese thought at large come to that. Thus it would seem that we have touched on a highly significant topic because this means that a signification, even if it would amount to little more than a mere rendering in process terms of Western notions as self and person and everything that hangs on them might make our dichotomies between nature and man, society and individual, and body and mind lose much of their strength.

In 1933 George Kates came to Peking, went native and began to sample the qualities of a civilization built on balance and decorum that survived down to the 1940s. After seven years of total immersion in the life of an old-fashioned Chinese scholar-aesthete the advancing Japanese sent him packing. This is what he had to say on the merit of devoted study of the classics:

“… those few oldest scholars, of the highest learning, of whom I had occasional glimpses in Peking during their sunset years, were so transmuted, had been made so human and so gentle by their long studies, that a complete justification of their own system spoke majestically from their faces. The visiting Westerner, however well informed, never fared well by comparison. For their own purposes the Chinese methods were supreme; and in communicating a tradition of enlightened living from generation to generation, their literature never failed them. This was the grand style; and it was to conserve this treasure that the art of Chinese writing had first been developed some three millennia back in the mists of the past. Much had meanwhile come and gone; much had failed of transmission, at least with the meaning and clarity that once had made it vital to the early sages; yet the old texts, unaltered, remained.”[30]

- Ames, R.T. (1994). The focus-field self in classical Confucianism. In R. Ames, W. Dissanayake, and T.P. Kasulis (Eds.). Self as person in Asian theory and practice (pp. 187-212). Albany: SUNY Press.

- Angle, S. (2003). Philosophy of governance. In A.S. Cua (Ed.). Encyclopedia of Chinese philosophy (pp. 534-540). New York: Routledge.

- Chan, Wing-tsit. (1963). A sourcebook in Chinese philosophy. Princeton: Princeton U.P.

- Cheng, Chung-ying (2003b). Ti: body or embodiment. In A.S. Cua (Ed.). Encyclopedia of Chinese philosophy (pp. 717-720). New York: Routledge.

- Hearnshaw, L.S. (1987). The shaping of modem psychology. London: Routledge.

- Ivanhoe, Ph.J. (2000). Confucian moral self cultivation. Indianapolis: Hackett Publ. Co.

- James, W. (1890/1950). The principles of psychology, Vol. I. New York. Dover Publ.

- Jullien, F. (1998). Un sage est sans idee. Paris: Editions du Seuil.

- Jullien, F. (2000). Detour and access: Strategies of meaning in China and Greece (Sophie Hawkes, transl.). New York: Zone Books.

- Kates, G.N. (1967). The years that were fat: The last of old China. Cambridge (MA): MIT Press.

- Nakamura, H. (1960). The ways of thinking of Eastern peoples. Tokyo: Printing Bureau, Japanese Government.

- Nylan, M. (2008). Boundaries of the body and body politic in early Confucian thought. In D. A. Bell (Ed.). Confucian political ethics (pp. 85-110). Princeton: Princeton U.P.

- Plaks, A. (Transl). (2003). To Da Xue and Chung Yung (The highest order of cultivation and On the practice of the mean). London: Penguin Books.

- Pongratz, L.J. (1967). Problemgeschichte der Psychologie. Bern: Francke Verlag.

- Rappard, J.F.H. van (1979). Psychology as self-knowledge (Transl. Liane Faili). Assen (Neth.): Van Gorcum.

- Rorty, R. (1980). Philosophy and the mirror of nature. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Rosemont, H. (2008). Civil society, government, and Confucianism: A commentary. In D.A. Bell (Ed.). Confucian political ethics (pp. 46-57). Princeton: Princeton U.P.

- Shun, Kwong-loi (2003). Xiushen (Hsiu-shen): Self-cultivation. In A. S. Cua (Ed.). Encyclopedia of Chinese philosophy (pp. 807-809). New York: Routledge

- Taylor, Ch. (1989). Sources of the self: The making of the modem identity. Cambridge: Cambridge U.P.

- Tu, Wei-ming (1985). Confucian thought: Selfhood as creative transformation. Albany: SUNY Press.

- Tu, Wei-ming (1994). Embodying the universe: A note on Confucian self-realization. In R.T. Ames, W. Dissanayake, and T.P. Kasulis (Eds.). Self as person in Asian theory and practice (pp. 177-186). Albany: SUNY Press.

[1] Read more on the Lun Yu of the Analects of Confucius.

[2] Nakamura, 1960, p. 206

[3] Source in the Public Domain of a hanging scroll, ink and colors on silk of the King Tang of Shang Dynasty – by Song Dynasty painter Ma Lin (1180–1256). Title Chinese: 《商湯王立像》- Series title Portraits from the Nanxun Hall. Painting is located in the National Palace Museum, Taipei.

[4] Read more on the “Doctrine of the Mean”

[5] Plaks, 2003, pp. xxx, xviii

[6] Chan, 1963, p. 98

[7] Read more on The Doctrine of the Mean

[8] Source in the Public Domain of Zhu Xi – Unknown author, Description: 中文:朱熹(1130-1200) 清人绘

閩南語 / Bân-lâm-gí:Tsu hi; Date Qing Dynasty

References 中国历史博物馆保管部, ed. (2003) 中国历代名人画像谱 2, 福州: 海峡文艺出版社, p. 26 ISBN: 7806407855. Source/Photographer scan from 《社会历史博物馆》 ISBN 7-5347-1397-8.

[9] Plaks, 2003, pp. 95-96, nn. 18, 19

[10] Chan, 1963, p. 97

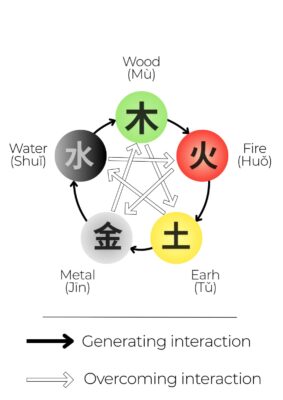

[11] Read more on wuxing. The “generative” cycle is illustrated by grey arrows running clockwise on the outside of the circle, while the “destructive” or “conquering” cycle is represented by red arrows inside the circle.

[12] Jullien, 1998; Plaks, 2002

[13] Read more on key concepts of Confucianism.,

[14] Ivanhoe, 2000, p. 4

[15] Shun, 2003, p. 808

[16] Shun, 2003, p. 809

[17] Nylan, 2008, p. 88

[18] Ames, 1994, p. 191

[19] Read more about William Stern

[20] Ames, 1994; Tu, 1994

[21] Rosemont, 2008, pp. 47, 51

[22] Angle, 2003, p. 628

[23] Tu, 1985, p. 74

[24] Tu, 1994, p. 180

[25] Read more about the Great Learning (Da Xue)

[26] Cheng, 2003b, p. 717

[27] Cheng, 2003b, p. 717

[28] Cheng, 2003b, p. 717

[29] Ames, 1994, p. 198

[30] Kates, 1967, p. 49