Hans van Rappard

3 ― From: Rappard, H. van (2009). Walking Two Roads- Accord and Separation In Chinese and Western Thought. Amsterdam: VU University Press. Chapter 1, pp. 43-50.

Enriched edition with illustrations and with the author’s permission.

part 1 – part 2 – part 3 – part 4 – part 5 – part 6 – part 7 – part 8 – part 9 – part 10 – part 11 – part 12 – part 13 – part 14 – part 15 – part 16 – part 17

The following section will be concerned with a significant aspect of the development of medicine in ancient China and Greece. In broad strokes it will be traced how medicine in the Western world progressed toward a mechanistic outlook, while medicine in China kept its initial perspective.

Greek medicine

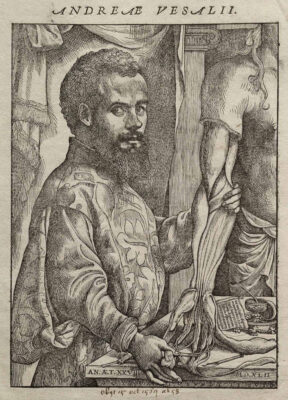

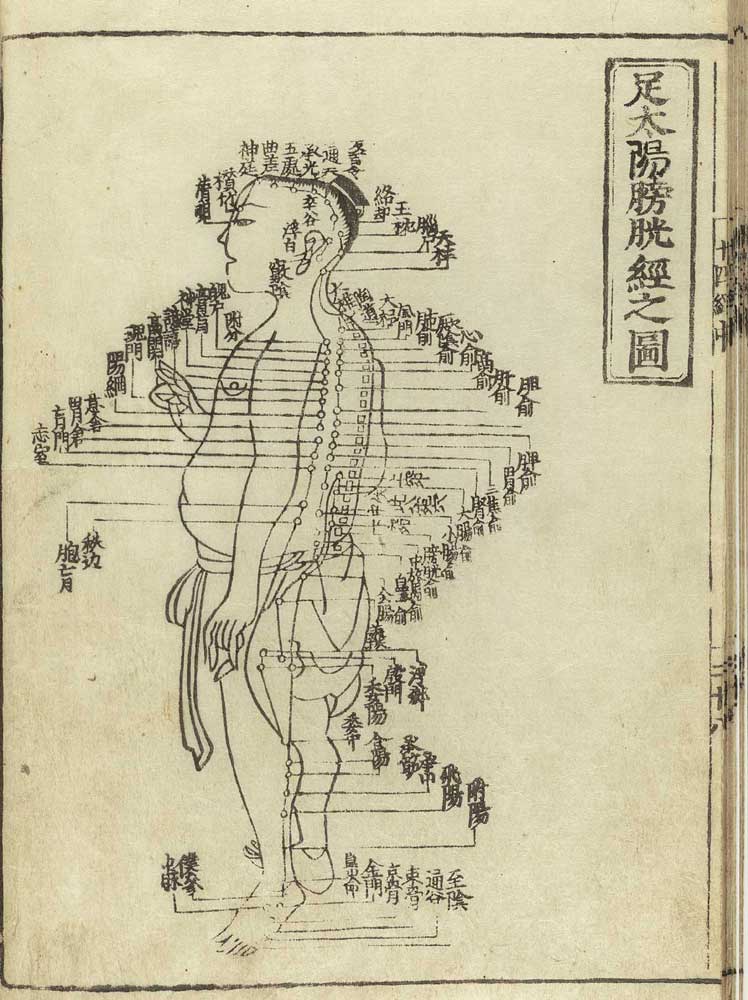

On the first pages of Kuriyama’s study of medicine in ancient Greece (The Expressiveness of the Body and the Divergence of Greek and Chinese Medicine, 1999) and China two pictures are printed, one of a 14th century Chinese and the other by Vesalius (1543) of a Western Renaissance man. Two pictures of the human body produced just two centuries apart, but the differences are striking: whereas the Chinese has been depicted quite flabbily ― a huge stomach curbed with difficulty by his loincloth and without a trace of muscles, the Vesalian man shows more muscularity than Rocky and Rambo between them could ever hope to develop.

But on the other hand, the tracts and points of acupuncture that are so carefully detailed on the Chinese are nowhere to be seen on the Western body.

Greek interest in musculature

The strong interest in musculature that is evident on many of our paintings, prints, and etchings dating from past centuries is a unique Western phenomenon. It can be traced to ancient Greece but did not emerge in any other ancient culture.

At first, the emphasis laid by the Greek doctors on the muscles of the human body might seem to be related to their interest in dissection and anatomy, which were accorded only minor significance by their Chinese colleagues.

But this would not be quite correct because the Greek eye for musculature can already be found at the time when they had not even tried their hands on animal and human bodies. At an early date, a kind of muscle-like ripples can be found in Greek art and human figures tended to be represented with bulging bundles of them. This was done already well before these ripples could have been identified as muscles and moreover, they were even pictured where the body has no muscles at all.

The art of reading character from physique

This would seem to suggest, Kuriyama says, that the artists did not intend so much to show specific physical structures as to give their figures a certain look.[3] Now, according to early Greek physiognomy, the art of reading character from physique, a strong character will reveal itself in feet and legs that are sinewy and well-joined, while brave souls manifest themselves in sinewy, clearly articulated ankles.

Poorly articulated (anarthroi) feet and ankles on the other hand, were assumed to betray weakness and cowardice. Indeed, lack of articulation marked a state of debilitation and exhaustion and of not yet being properly developed or immaturity.

Thus, arthroi referred not just to joints in the modem anatomical sense but also to the divisions and differentiations that gave the body distinct form. The appeal of articulation which, generally speaking, would sit well with the Greek penchant for clear and specific thought may in this case be linked in particular to their high esteem for strength and bravery. Well before they became fascinated with the muscles, the Greeks already celebrated bodies that had a certain look, a distinct ‘jointedness’, which was identified with these characteristics.

Nevertheless, it would probably be wrong to infer that the prowess of the Greek doctors at dissection and anatomy was totally disconnected from their fascination with muscularity. In contradistinction to their colleagues in the Egyptian, Indian, and Chinese centres of civilisation, they had come to value the inspection of the body over other methods of investigation so that their interest in the muscles may well have fallen on fertile ground.

We will return to this topic shortly, but what at this point concerns us more is the reason why the Greeks did develop an interest in anatomy at all, which, as mentioned, was quite anomalous in the history of medicine.

What exactly motivated them? After all, in many cultural traditions bodies were mutilated, entrails used for divination, or humans sacrificed ― opportunities galore to gather ‘inside’ knowledge of the body. Yet, except for Greece an understanding of bodily structure was developed nowhere else. But then, there was hardly any reason for it. The main cures in antiquity, bleeding, massage, and herbs did not require much anatomical knowledge so that increased knowledge of the body would not have much advanced ancient surgery.

On the usefulness of the parts

To appreciate Kuriyama’s answer to the question as to why the Greek doctors developed the art of anatomy, whereas their foreign colleagues did not in spite of ample opportunity to do so, we must turn to the work of the greatest doctor of antiquity, Galen (ca.130- 200).

Galen’s On the usefulness of the parts offers the most complete and detailed account of anatomical structure available at the time. Its significance is found in what may perhaps be called an early instance of the theory of intelligent design, namely the awe that Galen shows for the divine design of the body.

He demonstrates that every feature of it, however insignificant it might seem is actually indispensable and proves that everything is so well-disposed that it couldn’t possibly be better otherwise, thus testifying to the foresight and, no less important in the present context, also to the craftsmanship of nature.

Divine design and craftmanship

In other words, the anatomical interest of the Greek doctors[4] may be explained by their teleological perspective, which, as mentioned above, did not exist in the Chinese tradition.

“To know the body was to see how Nature shaped each part perfectly for its end, that is to say, its use …The core of anatomical curiosity lay here, in the vision of bodily forms as expressions of creative purpose … The evidence linking early anatomical inquiry with the belief in a preconceived plan is abundant and explicit …The presumption of divine design was absolutely critical to the enterprise of anatomy in just this way. It promised that a cadaver held more than frightening, repugnant gore ― that its contents displayed visible meaning.”[5]

Long before Galen, Plato had conceived already of a theory which understood the universe as created by a divine mind. It therefore manifests the rational purpose of its creator,

“whose handiwork constitutes a ‘cosmos’, a single, ordered, and beautiful whole, infused with life and intelligence.”[6]

The main elements of this theory are a transcendent maker and a model. The model consists of unchangeable forms or ideas, while the cosmos reflects their goodness and beauty. The maker on the other hand, is likened to a craftsman who creates the cosmos on the pattern of the ideas, which exist independently from him.

This, incidentally, puts the Platonic maker at a great distance from the God of Christianity, which is also demonstrated by the fact that the Greeks saw the (created!) cosmos as a god.

According to their scheme of things human beings are created by lesser gods, such as the Olympians, who are regarded as capricious spirits, sometimes helpful but harmful at other times. But we are not concerned with lesser gods but rather with the maker since it is his metaphoric craftsmanship that may explain the emergence of the anatomical interest of the Greeks.

Just as a craftsman when making a table keeps his eye on its idea or form, the eternal maker when fashioning the world kept an eye on the pattern of the eternal forms. It was this pattern,

“the forms envisioned by the creator, that defined the purpose of created things, their end. And it was these forms that the anatomist would eventually have to see.”[7]

The fact that the ancient Greeks began to think of the body as designed to achieve specific goals is a unique development whose importance is difficult to overrate, especially when compared to the notions formed by their Chinese counterparts.

Voluntary and involuntary processes

But the next move in the course of Greek medical thought is hardly less important. Given the significance accorded to the purposefulness of bodies, it is only logical that the Greek doctors also came to focus their attention on the question as to how the body worked. The two problems are difficult to separate. Once it is assumed that the body has been designed, the question naturally arises as to what end it was designed, after which the next question, how does it achieve its aim, inexorably follows.

In the attempt to solve these problems the human musculature had a highly significant role because the perception of the muscles as organs with specific functions induced the doctors to distinguish between bodily processes that may be influenced intentionally, and those that may not. In other words, they came to distinguish between voluntary processes or actions on the one hand, and involuntary processes on the other. Again it was Galen who had a major role in this development.

Galen[8] was struck by the observation that processes like digestion and heartbeat don’t need any attention and might even be disturbed if they could be focussed on, whereas other activities would just be impossible without it. We can, for instance, speed up our pace or enter this street rather than another but this means that we have deliberately chosen to do so and that the will has been involved.

Humans as agents

Moreover, and this is the crucial point, we cannot accomplish such actions without muscles. This may seem an innocuous fact but it was of sufficient importance for Galen to infer that the muscles allow people to choose what they do and that they should therefore be called the ‘organs of voluntary (chosen) motion’. One sees that it is choice that marks the divide between voluntary actions and involuntary processes and also that the muscles constitute the organs of the chosen actions. Having come this far, it was apparently not too big a step for Galen to draw the conclusion that it is the muscles that identify humans as ‘agents’. The modern concept of an agent refers to free, rational human beings who are capable of choice and thus may be deemed responsible for their actions. This is why Galen’s On the movement of muscles does not just describe muscular function but also goes into topics as action and self-awareness. Of course, these topics could only be treated rudimentarily at the time but nevertheless, the preoccupation with muscles, Kuriyama concludes,

“is inextricably intertwined with the emergence of a particular conception of personhood. Specifically, in tracing the crystallization of the concept of muscle, we are also, and not coincidentally, tracing the crystallization of the sense of an autonomous will. Interest in the muscularity of the body was inseparable from a preoccupation with the agency of the self.”[9]

Agency and self ― these modern-sounding terms will occupy us at a later stage, along with the question of whether counterparts can be found in the Chinese tradition. At this point it has to be kept in mind that the notions of action, agency, and self-consciousness could only have been developed elementarily by Galen, even if it is of monumental significance that they had been conceived of at all. It should also be kept in mind that whereas in the modern view agency and self presuppose persons who are autonomous and separate from the world, to Homer (8th c. BCE) such a conception would have seemed to stem from another world. In his work,

“the body doesn’t stand isolated and independent, shut up in itself, but ‘is fundamentally permeable to the forces that animate it, accessible to the intrusion of the vital powers that make it act… which, breathed into him by a god, run through and across him like a visitor coming from the outside’.”[10]

Thus, in Homer’s days, when courage, strength, or passion were still thought to manifest the influx of divine powers it would have been impossible to conceive of virtues and emotions as personal qualities rooted in an inner self. The third chapter will show that it took many centuries before this view became a possibility and then, again many centuries later, an unquestioned fact.

Given the importance ascribed to the notions of action, will, and self in the modern view of Western man, the split between voluntary action on the one hand, and involuntary or natural process on the other, is highly significant. To Kuriyama it is even a

“fundamental schism in Western self-understanding.”[11]

This paper will be brought to a close with a brief comparison of the ancient Greek and Chinese views of body parts, or organs, which will illustrate some of the importance of the action-process split.

A brief comparison of the ancient Greek and Chinese views

In the earliest Greek medical treatises the word organ (organon) is not yet found, and when it did appear it was in the context of a theory which was not

“a theory of processes that occur naturally, of themselves [but]a theory of action.”[12]

Recalling Ames’ cautionary remarks on the application of the organism metaphor to the Chinese worldview, one appreciates that ‘organ’ does not sit well with it either.

But to return to the Greeks, at first sight it would seem reasonable to categorise the various body parts found in dissection by means of criteria as shape, colour, texture, or location but this is not how they approached the matter.

Rather, what made a lump of flesh an organ in the eye of the early Western doctors was its role in some activity. Indeed, the decisive question was if a body part enabled an act, say, chopping wood or toiling the land.

Organs, as we have seen, were tools, and tools presuppose a user, just as purposefully designed bodies were used by their designer. Therefore, it was not only these useful bodies but also the organs employed in their construction that presupposed a user.

But at the other end of the Eurasian continent where teleological views did not obtain, organs were of course perceived quite differently.

The five ‘zang’ and the six ‘fu’

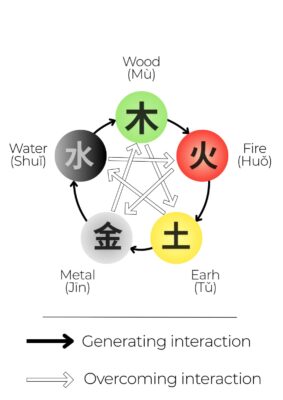

The Chinese view of the inside of the body was organised around the five zang and the six fu. The former were liver, heart, spleen, lungs, and kidneys, while the fu included gall bladder, small intestines, large intestines, stomach, and urinary bladder.

One would be excused for thinking that these lists referred to organs but we have to be careful with this translation because, among other reasons, the Chinese conception was not geared to anatomy but physiology and pathology. The Chinese were not so much concerned with what the viscera are ― that would tend towards the question about their essence ― as with what they do.

|

wu zang |

liu fu |

wuxing |

emotions |

taste |

|

heart & pericardium |

small intestine & triple warmer |

fire |

joy |

bitter |

|

liver |

gall bladder |

wood |

anger |

sour |

|

spleen |

stomach |

earth |

worry/ pensiveness |

sweet |

|

lungs |

large intestine |

metal |

grief/ sadness |

pungent |

|

kidneys |

urinary bladder |

water |

fear |

salty |

Each zang is paired with a fu, and each pair is assigned to one of the five phases (wuxing); the most common correspondences are listed[13]

The zang and fu have less to do with structures than with configurations of powers, which is not surprising in view of the dynamic nature of the five phases. While the zang and fu were not anatomically conceived like the Greek organs, they also differed in another and more fundamental way: they were not thought of as tools and hence could never presuppose a user. The “zang and the fu weren’t tools of some controlling source, weren’t implements of the soul. Literally, zang and fu both referred to repositories, and therein lay their principle role in the body. They both stored qi, vital breath.”[14]

Recall that the Greek word organ germinated in the hotbed of a theory of (volitional) action ― not a theory of (involuntary) processes.

Now, since according to the medical views of the Greeks action presupposed a user of the organs it would not seem unduly speculative to expect a Chinese theory of processes to get along without what their counterparts called a hegemonikon, a ruler or controller. And that’s the case indeed.

While the fu were hollow depots like stomach or bladder, which housed the coarser qi, the zang were the solid viscera that stored the finer qi. The zang, especially the kidneys, were considered more vital than the fu because they stored and, moreover, retained the purer qi, whereas the fu kept their courser contents only temporarily.

Thus, Kuriyama concludes,

“the hierarchy structuring the Chinese body was defined not by the [Greek] logic of ruler and ruled, but by the imperatives of storage and retention.”[15]

Clearly, there is nothing to be found in the way of a controlling authority, separate from the controlled structures. In this respect the medical views of the Chinese closely paralleled their cosmology.

- Ames, R.T. (1994). The focus-field self in classical Confucianism. In R. Ames, W. Dissanayake, and T.P. Kasulis (Eds.). Self as person in Asian theory and practice (pp. 187-212). Albany: SUNY Press.

- Chan, Wing-tsit. (1963). A sourcebook in Chinese philosophy. Princeton: Princeton U.P.

- Cheng, Chung-ying. (1989). Chinese metaphysics as non-metaphy- sics: Confucian and Daoist insights into the nature of reality. In R. E. Allinson (Ed.). Understanding the Chinese mind (pp. 167-208). Oxford: Oxford U.P.

- Cheng, Chung-ying. (2003a). Philosophy of change. In A.S. Cua (Ed.). Encyclopedia of Chinese philosophy (pp. 517-524). New York:

- Cheng, Chung-ying (2003b). Ti: body or embodiment. In A.S. Cua (Ed.). Encyclopedia of Chinese philosophy (pp. 717-720). New York:

- Fung, Yu-lan. (1960). A short history of Chinese philosophy. New York: Macmillan

- Fung, Yu-lan. (Transi). (1931/1995). A Taoist classic: Chuang-tzu. A new selected translation with an exposition of the philosophy of Kuo Hsiang. Beijing: Foreign Languages Press.

- Jullien, F. (2000). Detour and access: Strategies of meaning in China and Greece (Sophie Hawkes, transl.). New York: Zone Books.

- Kuriyama, S. (1999)- The expressiveness of the body and the divergence of Greek and Chinese medicine. New York: Zone Books.

- LinYu-tang. (1967). The Chinese theory of art. London: Heinemann

- Liu Dan Zhai. (1996). Paintings and calligraphy. Shanghai: Shanghai Shu-hua Chubanshe.

- Lloyd, G.E.R. (2002). The ambitions of curiosity: Understanding the world in ancient Greece and China. Cambridge: Cambridge U.P.

- Lloyd, G.E.R. & Sivin, N. (2002). The way and the word: Science and medicine in early China and Greece. New Haven: Yale U.P.

- Luce, J.V. (1992). An introduction to Greek philosophy. London: Thames and Hudson.

- Needham, J. (1956). Science and civilisation in China, Vol. 2, History of scientific thought. Cambridge: Cambridge U.P.

- Ronan, C.A. (1978). The shorter science and civilisation in China ― An abridgement of Joseph Needham’s original text, Vol. 1. Cambridge: Cambridge U.P.

- Soothill, W.E. (Transi). (1910/1995). Confucius, The Analects. New York: Dover Publ.

- Watts, A. (1954). The wisdom of uncertainty. London: Rider.

- Yip, W-L. (1976). Chinese poetry. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Yu, Jiyuan. (1999). The language of being: Between Aristotle and Chinese philosophy. International Philosophical Quarterly, 39, 439-454.

[1] Source in the Public Domain of a Portrait of Vesalius, Attributed to Jan van Calcar (circa 1499–1546/1550)

“Portrait of Vesalius from his De humani corporis fabrica”. Date 1543; Source/Photographer Unknown source.

[2] Source in the Public Domain of Acupuncture chart from Hua Shou (fl. 1340s, Yuan dynasty). This image from Shi si jing fa hui (Expression of the Fourteen Meridians)

[3] Kuriyama, 1999, p. 134

[4] Read more on Hippokrates

[5] Kuriyama, 1999, pp. 123-125

[6] Luce, 1992, p. 107

[7] Kuriyama, 1999, p. 125

[8] Read more about Galen

[9] Kuriyama, 1999, p. 144

[10] Kuriyama, 1999, p. 146

[11] Kuriyama, 1999, p. 151

[12] Kuriyama, 1999, p. 263

[13] See: Wu zang liu fu (五臟六腑) in Traditional Chinese Medicine (December 29, 2016) by The A.I.M. Therapy https://www.theaimtherapy.com/wu-zang-liu-fu-五臟六腑-in-traditional-chinese-medicine. Accessed at 2021-04-03.

[14] Kuriyama, 1999, p. 266

[15] Kuriyama, 1999, p. 266