Erik Hoogcarspel

Je voy que les callibistrys des femmes de ce pays sont à meilleur marché que les pierres. Diceulx fauldroit bastir les murailles …

Rabelais (Pantagruel XV)[1]

Introduction

The subject of this paper is the practice of tàijí and the way it deals with violence. Tàijí is considered to be a martial art, but unlike the usual ones, it does not seem to include the use of violence. Therefore it is qualified as internal, in opposition to external martial arts like gōngfū, kickboxing or sanda.

In the practice of tàijí though, it looks like at least some violence is included, it is clear that kicks and punches are thrown.

I will argue that tàijí is essentially not a martial art but a self-technique[2] and that this explains the poor performance of tàijí masters in contests of martial arts. In order to do this I will use the phenomenological and eidetic reduction, but I will show that the practice of tàijí includes such reductions as well and that it reveals what Merleau-Ponty called the flesh of the world. Finally, I will show how tàijí can be understood from this phenomenological point of view and that its essence transcends our conventional concepts of time, space and causality.

A historical fight

In 2017 a public challenge took place between tàijí master Wei Lei and a M.M.A. (mixed martial arts) fighter Xù Xiăodōng.

Although Mr. Wei was known for his expertise in the control of qì (energy), it took however the M.M.A. fighter not more than six seconds to beat him to the floor. Apparently the qì had a day off, because the tàijí master didn’t even stand a chance.[3]

The Chinese media were replete with protests and accusations to Mr. Xù for having insulted the Chinese cultural tradition.[4]

Mr. Xù Xiăodōng didn’t stop just at one fight, he kept going on beating the crap out of self-proclaimed tàijí masters, making the complete tàijí-tradition to lose face, and with this the complete gōngfū or Chinese martial art movie industry.

The authorities made him an outcast

As a result the authorities made him an outcast. He was denied the right to travel in bullet trains and by air and his Weibo and Wechat accounts have been closed time and again for all kinds of reasons. Apparently the exposure of the false pretense of masters of soft martial arts is not very much appreciated by the authorities.

This is not hard to understand. All over the world people take classes in Chinese martial arts and believe that this will enable them to defend themselves in the streets.

Luckily most people don’t run into real street fights, so they never have to test the usefulness of what they have learned. In a way Mr. Xù has done this for them.

Besides, the fame of Chinese martial arts in general made a lot of movie directors and martial arts teachers very rich.

Tàijí: the pinnacle of pugilism

In Chinese culture tàijí is regarded to be the pinnacle of pugilism, meaning that a real master should be capable to win a fight with any specialist of a so called external martial art without even exerting himself. We see this however only in the movies.

On the internet there are numerous fights to be found between tàijí masters and experts in other styles of pugilism. In all of these fights the performance of tàijí does not look like the typical soft and internal martial art it is supposed to be.

It turns always out as a kind of gōngfū, which makes sense, because the only way to win a fight is to inflict real damage to a real opponent. If a tàijí practitioner merely tries to push his opponent or throw him to the ground, the latter just keeps coming back until he has inflicted some serious damage.

Tàijí has been associated with the traditions that are considered to be typical Chinese like the system of Chinese medicine and the Daoist internal alchemy (nèidān, 内丹).

In this way it has evolved from a martial art into an art of longevity and transcendence[5], which in China is often called immortality. This is however stuff for the advanced practitioners, it is not revealed to beginners who just take a few classes in order to stay fit.

Chineseness

In general tàijí is considered to be unique for the Chinese symbolic institution or culture. Talent and feeling for tàijí is an element of Chineseness, and it continues to be propagated as a kind of magic by the bulk of gōngfū films that are flooding not only the Chinese but also the Western cinemas.[6]

In most cases the theme is the myth of the lone fighter, who is often an elderly master. In spite of his age, his abilities exceed those of young men: he is able to jump up to four meters high or more, or even fly in the air, and he can defeat a whole army just by waving his hands.

Medical research has established that the practice of tàijí causes significant improvement of balance, muscle strength and cardiovascular health, but not to such extent.[7]

Douglas Wile points out why tàijí is considered such a precious part of the Chinese culture. Although its roots probably are much older, it became known to the public during the latter half of the 19th century, when the sentiment of Chineseness and the national pride were under heavy pressure.

The claim that the inner force is superior to the outer one

The claim of tàijí masters that the inner force is superior to the outer one reaffirmed symbolically the hope that the Chinese cultural power would overcome the dominance of the Manchu reign and the invading Western military forces.

The Boxers Rebellion however was a disaster, because the boxers appeared to be vulnerable to the bullets of Western rifles in spite of their magical protection. This did not take away the confidence in the superior powers of tàijí.

So the question is: is tàijí a kind of cult, are all these stories about tàijí masters just a myth? Or is tàijí a supreme bag of tricks with which one can outsmart any rough?

The symbolism of sport

The importance of an official boxing contest in the European symbolic institutions has been observed by Jean-Paul Sartre. He describes how in each boxing match the complete boxing tradition is present. It is not a matter of two individuals who just happen to meet and decide to beat the crap out of each other. Just like in China it is a matter of tradition and history. According to his view a match is nothing less than the incarnation of the entire boxing tradition.[9]

…on comprendra sans peine que la boxe tout entière est présente à chaque moment du combat comme sport et comme technique, avec toutes les qualités humaines et tout le conditionnement matériel (entraînement, conditions de santé, etc.) qu’elle exige. Par là il faut entendre que le public est venu voir et que les organisateurs se sont arrangés (bien ou mal) pour lui donner de la belle boxe. … La boxe est là, comme hexis, comme technique et comme invention toujours neuve de chacun.[10]

Sartre (1985)

This explains why the discourse in all kinds of sports are so elaborate and emotional. Usually there are verbose commentaries, reviews and previews after and before important matches. Onlookers talk among each other about what they see, comparing it with the achievements of the great sports heroes.

Some sports have become big industries thriving on this daily conversation like baseball and basketball in the U.S. and football or soccer in Europe. In China martial arts used traditionally to be performed in operas and in folk theater too.

This explains why sport in general and boxing in particular is shrouded in all kinds of symbolism and myth.

Violence

Soft martial arts are said to be less or even nonviolent. There are however different kinds of violence and understanding them may explain why Mr. Xù usually has the overhand.[11]

The degree of violence that is permitted in M.M.A. is high, although it is not as destructive as in a street fight. In M.M.A. the powers of aggression and resistance are more prominent than in most other martial arts.

Wild violence is about hormones, instincts, anger, fear, determination and opportunism

According to Barry Allen, the raw violence, I call it wild violence, that happens in street fights is about hormones, instincts, anger, fear, determination and opportunism.

Many karate masters, he writes, even admit that they are not sure how they would perform in the streets. The best weapons in the streets are unpredictability, cruelty, opportunism, deceit and swiftness. You have to be prepared to kill[12]. Wild violence is unpredictable and you need to be on edge for it.

With few exceptions, people, even seasoned perpetrators, are tense and fearful when violence is imminent.[13]

Loïc Wacquant has shown that tamed violence like in boxing is a self-technique that even helps street fighters to abstain from wild violence[14] by taming fear and aggression through discipline and learning to see the opponent as a subject.

Breaking through the defenses of opponents by force

The best M.M.A. fighters and boxers retain however a kind of killer instinct that puts them into the rage of a disciplined fighting machine, producing continuous series of blows and kicks, breaking through the defense system of their opponent. Their training has to make sure that the damage they cause is limited, although accidents happen.

This is clearly visible in the clip of Mr. Xù, he really gets physical, he uses his weight, his muscles and breaks through the defenses of his opponent by force.

The latter freezes and cannot help himself to avoid a beating. In the practice of tàijí this kind of violent rage of force and speed does not occur because it is regarded as an ineffective waste of energy.

Violence is part and parcel of human history

In our world violence seems to be unavoidable, it is part and parcel of human history and it comes in several forms. There is not only physical violence, Jean-Paul Sartre has described a kind of violence being induced by scarcity in his Critique de la Raison Dialectique I[15]. John Galtung has described structural violence in his article Violence, Peace, and Peace Research (1969), and Pierre Bourdieu has coined the concept of symbolic violence[16]. Besides, Sartre has described the violence of the gaze, the judgment of the other, which is continuously threatening our freedom[17].

The multitude of theories and the different kinds of violence however induce the risk of stretching the concept to such an extent that it becomes too vague and opaque. We have to narrow it down somehow and get to the essence.

In his Cahiers pour une Morale Sartre[18] identifies violence with the use of force[19].

This is clearly wrong, because there are situations in which the use of force is benevolent, for instance when one has to smash a window in order to save someone out of a sinking car.

In many cases violence even does not require any force. In most penal codes for instance poisoning or lethal sabotage is considered to be manslaughter, which indicates that it is considered to be a kind of violence. This kind of violence might be called cold violence, it is the attempt to hurt someone through manipulation.

The essence of violence becomes clear when we leave all facts and specific examples aside. In phenomenology this is called an eidetic reduction[20]. The focus of the inquiry is on potentiality rather than actuality, and as a consequence sociological or biological data become irrelevant, because it is all about the a priori aspects rather than the a posteriori ones[21]. This inquiry is focused on the nature of violence.

The root of violence is the principle of fighting

The root of all violence is the principle of fighting and this entails basically the intention to kill someone or if tamed, the intention to hurt. A drone attack on guerrilla fighters somewhere far away, an offer you cannot refuse, the use of teargas, are all different kinds of fights, sometimes by proxy.

On all those occasions there is an attempt to break someone’s resistance and to destroy her power and freedom. The opponent is turned into an object that has to be eliminated or neutralized. In a contest it is from the beginning understood that both parties will always have a second chance, so they are recognized as subjects and killing is out of the question. A contest may be tamed violence, but retain some of the feeling as a motivation, like a kickboxing champion once said in an interview: When I see someone enter the ring I want to destroy her because she had the nerve to invade my space.

Violence is often related to pain, but pain is only the result of violence if it is meant to harm. A root canal treatment causes pain, but it is not violence because it is beneficial and the dentist accepts you as a subject and does not want you to suffer. An object does not feel pain.

Sartre has made clear that pain is used as a means to control a threatening other by turning her into an object. A sadist enjoys the pain he causes in others, just as long as he sees his victim as a subject, if he succeeds in making him into an object, the game is over. His situation is then like someone who is playing a chess game with the computer, and suddenly pulls the plug saying now what is your next move!.

Violence does not go well with emotions in general, because when you are angry at someone, you recognize him as a subject. This is still the case when this anger expresses itself in attempts to hurt him. The real violence starts when the anger does not subside and you are really trying to eliminate the person or cause as much damage as possible. In that case the person has become an object.

Unavoidable to accept some violence

It seems unavoidable to accept some violence. Most of the time violence is even not experienced as such. For violence to reveal itself as such it has to be a discontinuation of daily life, it has to be out of the ordinary, in other words it has to look wild. Sometimes violence that has been accepted for some time suddenly appears to be unacceptable and causes protest or resistance.

The concept of violence includes a sense of something being wrong, the feeling that what happened should not be tolerated. Because it is out of the ordinary, wild violence is associated with contingency. Dodd comments:

That is, the question is whether the tendency to deproblematize violence, in the wake of the progressive deproblematization of agency, polity, and history in ever more robust conceptual schemes, in fact shortens our view of violence in a manner that begs the question of our ultimate relation to the unintelligible as such. Thus the risk we assume in attempting to articulate a coherent, stable concept of violence is our exposure to the tendency of our concepts to turn our gaze away from the potential for violence to be seen as something that resists concepts, and yet for all that is not nothing.[22]

Violence has according to Dodd to maintain a certain sense of the explainable, otherwise it would become acceptable and thereby lose its essential quality. The concept of wild includes this sense of contingency and incomprehensibility.

Beyond violence

The reason why tàijí masters don’t seem to perform very well in a serious fight becomes clear when one visits their respective training sessions. Gōngfū training is not only about skill, but also about force and velocity, it is about violence.

To hit with more force and speed and before

One has to learn not only to outsmart an opponent, but also to hit him with more force and speed and hit him before he hits you. It is also important to hide ones intentions and to deceive the opponent so that you have the advantage of a surprise and the opponent is too confused to organize adequate defensive tactics. He is the dangerous object that has to be neutralized. It is also important to be able to take a few blows, withstand pressure and not to freeze in front of imminent danger.

Therefore it is an advantage to have strong muscles and strong bones, so heavy weights are generally more successful. It is important to spar with a partner in order to test ones abilities. While sparring it is important to wear protection, so that real violence can be enacted. Part of the fight is the will to really hurt the opponent. Aggression is a part of the fight, although it has to be disciplined. The movements are fast, wide and expanded, muscles are tense, the body and the arms are often stretched as much as possible. This kind of martial art is linked to war.

Tàijí is just to ward off a virtual attack

Tàijí[23] is the opposite. Although the movements have the same structure, the aim is not to neutralize a dangerous object, but just to ward off a virtual attack. There is no aggression, no violence.

So a fight is usually between two subjects who see each other as objects that have to be neutralized. Fighting has to be efficient and with as little emotion as possible. In tàijí not only the subject is put aside, but also the object. While doing the form there is nothing to be neutralized and that is why the practice is a self-technique.

Doing the form

Tàijí is performed by people of all ages and strength. It is practiced very slowly and one doesn’t develop very strong muscles. Every movement has to be performed with easiness and comfort. There is no intention to hurt anyone and no aggression.

The attention is focused on one’s own body. Every muscle is observed and has to have the right tension or relaxation.

A self-technique for improvement of physical and mental well being

The technique is a self-technique, which means that the movements are not performed in order to change things outside, but to effect changes one’s own body. So, in the practice of tàijí the aim is not to hurt an opponent, but to do the right thing in the right way at the right moment. The movements have to feel right.

The benefits of the practice of tàijí are all in the field of improvement of physical and mental well being. One doesn’t become a mighty fighter, who inspires fear in his enemies, one becomes soft, easygoing, kind and relaxed.

It may be that someone who is soft has some extra leverage over someone who is tense, but there is no doubt that in the end muscles always win. No one wins a war by using tàijí. Tàijí involves no winning or losing. It is even contrary to the principle of tàijí to try to be faster than others.

The movements and the sequences of movements take their own time. There are several forms, each consisting of fixed sequences of movements and each form has its own duration. The Yang 24 form for instance takes ideally about five minutes. The practitioner ideally should not worry about what to do next or how fast she has to move. She just has to relax and let the form take its course. Her attention is directed solely to the way the form takes shape. Even pushing hands is not about winning. It is a contest and mainly about self-improvement and learning to understand the flow of qì.

A change of consciousness takes place

It is clear that while doing a form a change of consciousness takes place. The focus on what to do and on how things are, changes into a wider one that oversees the body and its movements. Tàijí is meditation in movement on movement.

Because one is not focused on the results of the movements, the mind feels quite united with the body. When I am walking to the tàijí class for instance, my focus is on the street, the cars and bicycles passing by and on the traffic lights, but not on what I am actually doing. When I am walking in the park my thoughts are with what I see or who I am talking to.

When I am doing tàijí however, I try to be focused on what I am doing and on nothing else. Because the result of a movement in tàijí is the movement itself. There is no end to each movement, it just merges into the next one, just like the awareness.

This change of consciousness is known in philosophy as a phenomenological reduction of consciousness[24], because we are no longer aware of the world, but just of the phenomena, that what presents itself to us.

Movement

Our view of the world is largely determined by science. The scientific view of things is that they are out there and that we can only know them through the stimuli that our senses pick up, in other words by means of perception.

This theory is called empiricism. John Locke (1632-1704), arguably the father of empiricism, was convinced that we can only experience perception, not explain it (scientifically).[25]

According to him we are unable to know the physical substances we perceive, only God is, therefore He is the only one Who knows how perception really works.

Today we have worked out causal explanations of most perceptional processes, but we still do not know how material stimuli give rise to ideas and emotions (some philosophers call this after David Chalmers the hard problem of consciousness). This dualistic structure of empiricism has been taken for granted in all scientific discourse, where now machines are used to discover the hitherto unknown states of affairs that Locke called physical essences or imperceptible structures of the world.

These structures are considered to be more real than the perceptible ones, which has led to a disdain for the world of daily experience.

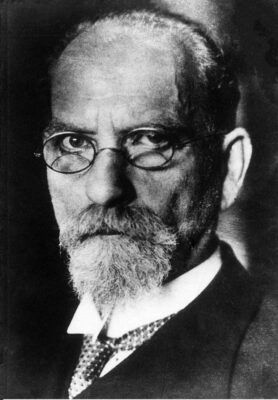

Edmund Husserl has described this problem in 1935, in his famous lecture De Krise der europäischen Wissenschaften und die transcendentale Phänomenologie[27].

Husserl explains that science has hidden our direct experience of the world under a veil of theories and scientific concepts which are ultimately derived from this direct experience, but distorted and impoverished.

As an example we can take the concept of movement, which used to mean any kind of change. Most antique philosophers agreed that things are impermanent, and that true knowledge is unchanging because it does not just stop with things, but reaches out to the unchanging essences behind them. Movement was linked to time and part of everything on earth.

In tàijí most movements are circular

We see that in tàijí most movements are circular and not straight. They are very efficient, they have the efficiency of the body. The first walking robots created by mechanics were very inefficient, they used a lot of energy and were also unstable. Even now no robot is walking as efficiently as our bodies do.

Efficiency is very important in gōngfū, but this is a kind of efficiency that is determined by the will not by the body. This is mechanical efficiency such as the force and velocity of a punch or kick. It can be measured and compared to performances of robots.

The efficiency of tàijí is illustrated by the story about the old tree in the Zhuāngzi.[28]

The tree is crooked and useless because it does not meet any external standards. So the carpenter asks Zhuāng Zi

“What can we do with this useless tree?”

“Well, says Zhuāng Zi, this tree will still be there when all the other straight ones have fallen to the ax of carpenters and turned into doors and furniture. As long as it exists it will provide ample place for the birds to safely build their nests and shade for tired passers-by to take a quite nap.”

So tàijí is efficient by its own standards, those of the flesh of the world, just like the old tree, that’s why it is so valuable. That is the reason it promotes health, well being and even immortality. It transcends the standards of the efficiency of gain and loss.

The from where, the going to and the way are not separate entities

This kind of efficiency is related to a special concept of movement. The philosopher Martin Heidegger (1889-1976) while analyzing the concept of Nature in Aristotle’s physics B1, wrote that nature shows itself by coming into appearance in a way in which the from where, the going to and the way are not separate entities.[29]

As a consequence Nature has its telos (and origin) in itself. This reminds us of the concept of dào in Chinese philosophy.

Usually things come from somewhere and are going somewhere, they have a starting point and a destination. According to the mechanical efficiency, the movement which takes place between both is a waste of time. Therefore, a movement that is called efficient is as short as possible. This is the essence of a straight line being the shortest distance between two points, which is the natural movement in modern philosophy.

The God of Descartes does not waste time, only humans do, when they allow chaos and collisions.

We don’t like to waste time

We usually don’t like to waste time in daily life either. Roads are as straight as possible and boats and airplanes don’t usually move in circles. The boats that avoid straight lines are cruise ships. During a cruise the voyage is the destination, but there still is a reason to go on a cruise and that is to have fun.

Doing tàijí is like doing a cruise, the movement is the starting point and the destination, but you don’t do tàijí just for fun. If you do this or if you are taking it up because you would like to become a more successful businessman, or an immortal for that matter, you are missing the essence.

In order to learn tàijí you have to abandon the world outside, forget all about purpose and usefulness and be the movement. If you are the movement, the movement doesn’t stop, but merges into the next movement. When the form is finished you come back into the world of purpose and need.

Life is a journey from birth to death, there is an origin and a destination. If life would be like tàijí, if origin and destination would be transcended, there would be immortality. This is in my opinion the meaning of the title of the first chapter of the Zhuāngzi: called ‘Happy Wandering’ (xiāoyáo yŏu, .逍遙遊). It means moving in such a way that origin as well as destination are part of the actual movement itself and not outside of it.

Time

Being the movement implies a new experience of time. Normally time is never now. It is only past and future. Looking at an analogical clock you see that the hand that shows the seconds never stops (in some clocks it actually does, but that is not correct because time is supposed to be continuous without intervals), it is moving all the time which means it is never anywhere. You only can see where it came from and where it is heading.

This is the way we normally experience our life, we have duties and needs that came from the past and that are pushing us towards the future. The duties and needs are all from a past that never was a present, they are pushing us towards a future that will never become a present either.

When I feel thirsty and I am walking to the fridge to grab a soda for instance, my experience of being thirsty, beginning with the first impulse, changes all the time.

When I remember my first impression of feeling thirsty during my journey to the fridge, it is already different from the actual experience that took place a moment ago. When I am finally drinking my soda the experience is different from what I initially thought it would be. Experience always has an element of surprise.

She is the movement herself

When someone is doing tàijí she is not looking at something that moves, she is the movement herself. When she experiences the tàijí reduction of consciousness and there does not arise any doubt about what the next move should be, the past and the future dissolve into the present, so there is only now.

Tàijí has to flow like the way a silk tread is won from a pod: smoothly and without interruptions. In other words, every sense of resistance has disappeared. Because the form is practiced slowly, the practitioner is aware of every movement in each moment and simultaneously of the sequence of movements.[30]

The form does not end in a conclusion

Past and future merge also in another way because in tàijí the form does not end in a conclusion. There are no winners or losers and nothing is accomplished. The training never ends. The world has not changed and the only thing to do is to start right again from the beginning. The forms are circular, the place where you start is not different from the place where you end up.

We can understand now that there are different ways to practice tàijí. What we just have discussed is the way tàijí is practiced as a self-technique, the training of forms, called tàolù. There is however no law against practicing it as an art of self-defense, as a bag of tricks that can possibly limit the damage in situations of wild violence.

Some people practice tàijí as a sport, as a kind of gymnastics, or as a kind of ballet. Besides, many people practice tàijí as a game, this is called pushing hands or tūi shŏu.

All those practices are however functions (yòng, 用) of tàijí, they are not its principle[31] (理, lǐ).

Vital space

The experience of space in tàijí is important because we need space in order to move. Apart from the physical space we need for doing the form, there is the experience of the space of living. In physical space width, breadth and dept are of equal importance. Together they are called the three dimensions, the three ways of measuring a thing.

If we move we find that the depth is much more important than the other two dimensions, because moving is nothing but the experience of depth. In our field of vision depth makes it possible that things have a back side, that they don’t reveal themselves completely and that they hide each other and themselves totally or partially, in other words that they are open for further exploration.

Depth is all around us, but we are just open to a part of it, which is our front. If we would be open to all sides equally, we would not be able to move forward. We would not be able to decide, like in the case of ass in the example of church father Buridan who died of hunger because it was positioned right in the middle between two bags of oat and it couldn’t decide from which bag it would like to eat first.

Our body provides us with an orientation, which is however flexible. Merleau-Ponty remarks that our world would have been very different if our bodies would have a different structure, for instance if we would have been able to see more of our body or if we would have had protruded eyes.

Internal and external horizon

Space is limited by its horizon. The body has its internal and external horizon.

The internal one is the structure of its very own qualities. It consists of all the possibilities it possesses to interact with things in the world.

The external horizon of the body consists of all of the different ways in which it is determined by the states of affairs in the world. In Chinese philosophy both are not very different. Both are each other’s metaphor.

The emotions and desires for instance, which are the way the body is affected by the world, are related to the internal organs and perception which are basically physical functions[32]. The internal horizon of the body is sometimes represented in the form of a landscape and many of its names refer to its external horizon. So the body is what it does, that is why doing tàijí changes the body.

The correlation does not mean that the body is a black box, in that case we could ignore the internal horizon, because everything would be external. It means that both horizons are not separated by an impermeable skin, they are interdependent and determine each other. We experience this for instance when we find our world to become smaller when we are ill or very tired, or when the world reflects strong emotions.

Repetition for Practice

Merleau-Ponty stressed that we do not exist in the world, but rather towards it. We are not in the world like a shoe is in a box for instance. When someone takes the shoe out of the box, the shoe nor the box are changing in any way. When we leave the world however, it is not the same anymore nor are we. We are constantly engaged in the world and we as well as the world are part of this very engagement. This engagement continuously becomes a living experience through our bodies.

While we are living our different types of engagement, our body is transparent. We are not aware of the different tensions in our muscles when we are walking for instance. Only when we have problems with walking we are. In such moments our body becomes opaque and we become aware of its internal structure and its internal horizon. Otherwise we are aware of the world, its structures and its own internal horizon, which appears to be the external horizon of our body. This is the structure of the I can, our engaged self-consciousness of what we can and cannot do with our body.

Repetition makes it easier

By repetition a movement becomes easier, which means that our internal horizon increases. People who are used to walk a lot find this easy to do, the resistance they experience while walking has diminished. This causes an experience of freedom, an experience of an opening horizon, of depth and adventure. At the same time we can walk longer distances, which means that we have more options, our external horizon also increases. In short, repetition makes that we find doing things easier and that we can do more.

This also happens in the practice of tàijí. The form is repeated again and again and in due time it becomes more comfortable to do and the practitioner develops her skill and her horizon.

The repetition of the form is a repetition without original. The repetition started with repeating the example of the teacher, off course, but she only can show repetitions of what her teacher showed her and so on. The original does not exist and is ascribed to a legendary or mythical person.

This means that the repetition will never end, because it is impossible to restore the origin, to perform a repetition that is exactly the same as the original. Each time the repetition nevertheless improves, in an endless process of perfection.

Tàijí: the form is getting easier, but we’re never done

When we are doing exercises, we usually aim to achieve some skill, like performing a handstand or running a marathon for instance. The performance we train for will be something we can show others. The more we do this, the more our body becomes transparent and the performance becomes a fact that is part of the world. We feel proud we can do it, it is our performance and for us it has become a piece of cake, or a walk in the park.

The practice of tàijí has the same aspect, we find it more and more easy to do the form, but we are never finished, our skill never becomes a fact of the world, we are never completely there and there is no reason to be proud of anything. The ease of doing the form however is very comforting and relaxing.

Usually a repetition has a start and an end at some point. Walking consists of a repeating movement, that starts at the beginning and stops when we cease the activity.

On a deeper level however, we find in this case a repetition without original too, because every moment during our walk and during the rest of our lives has a past that never was present and a future that never will become such.

When we pay attention to the present, we usually assume that it does have a past. We are walking now and we know where and when we started. This memory of the beginning is however a representation and not the actual experience. The moment we started to walk is not the same as the present moment when we remember it. We might have the intention to tell about this moment to someone else tomorrow, but that moment will again be different from the present moment when we feel the intention. Time cannot be reversed.

The flesh of the world

This is exactly like the repetition of the tàijí-form, every moment is a fresh start because it is a repetition without original. So the practice of tàijí brings us to another, deeper level of time that usually is overlooked in daily life. This is the level of what the French philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty called the flesh of the world.

The flesh of the world is living, it is not a readymade stuff that is put into place for us to have fun with. It is the living correlativity of the one who perceives and the perception and it is beyond the split into self, object and other.

Painters have found that photographs don’t show the world as we perceive it, because our perception is always moving. We move our head, our eyes and our eyeballs and our focus changes continuously, this is part of our very perception. It gives every perception a depth and makes us engaged in what we perceive.

A photograph is a static and artificial imitation of a frozen moment in our perceptive life. A drawing that is made according to the rules of geometrical perspective is based on pure geometrical shapes, which are nonexistent products of the mathematical imagination.

In our lived reality there are no geometrical shapes, like circles, squares or ellipses. Everything is distorted and unstable because of our physical presence. That is why paintings both in Western as Chinese art show often different perspectives merged in the same painting.

Space and freedom

The ethical aspect of this movement and instability is that there is always space and freedom. Without space no movement is possible and without instability nothing could change and there would be nothing to choose or to hope for.

No one can live in a photograph, but your mind can live in a painting if it has enough space and instability.

Now it looks like there is no freedom in doing a tàijí form, because the teacher time and again corrects the pupil. If there would be a dào that could be shown or followed, if there would be a perfect way to do the form, this would certainly be the case.

However there is not. Doing the form is even not about achieving perfection, it is about doing the form as well as you can, with unwavering attention. This is always good enough, this is always already perfect.

This is a kind of freedom, not a freedom in the sense of that you can do whatever you like, but a freedom from the urge to do what you like, a peace of mind, ataraxia[33] as the ancient Greek called it. Even tūishŏu or pushing hands is not about winning, but about friendship, two people playing a game and getting to know one another.

At this point many people might disagree, because there is a lot of competition and authority in circles of tàijí, but I would argue that this is just manifestation and not principle.

In order to discover the principle one needs to perform what is called a phenomenological reduction, which is to disregard the world of conventions and institutions and get back to what just appears as such. In doing tàijí we actually do this when we focus upon the experience of the movements.

The structure of the body

Maurice Merleau-Ponty[34] is a philosopher who focused in his earlier works, ‘La Structure du Comportement’ and ‘La Phénoménologie de la Perception’, on the experience of our bodily actions as well as on our spatial and temporal orientations and physical experience. This approach enables us to understand the principle of tàijí.

Merleau-Ponty shows how we inhabit space and time by being our body and how we are introduced into a new world when we acquire new kinds of perception. As Merleau-Ponty points out, our moving body is the essence of our existence in the world.

In the same way we will have to awaken the experience of the world the way it appears to us in so far as we are to the world through our body, in so far as we perceive the world with our body. If we reconnect however with the body and the world this way, we will find also ourselves again, because the body is a natural me and the subject of perception if one perceives with the body.[35]

The virtual opponent brings all movements together into one focus, which is related to the body, Merleau-Ponty explains:

The unity of the object in the experience of perception is just another aspect of the identity of our own body during the movements of our exploration. So the one is equal to the other. Like the body outline any object is a system of equivalences that is not based on any recognition of a law, but on the experience of a bodily presence.[36]

Embodied space

Space is phenomenologically nothing but the possibility to move, it is embodied space. Merleau-Ponty mentions the example of a football player[37], the field is not a neutral space where he happens to be, it is an extension of his own body (il fait corps avec lui, he embodies it).

The football player has become the owner of his movements through practice. These movements are not the mechanical ones of modernity and science, they are circular and in harmony with the body. The purpose of football (or soccer) training is to obtain full control over one’s own space this way. The space is circular and usually controlled from the center of the body.

The body is however not a readymade prison of the soul, it is a living presence that develops through movement.

The movements of tàijí too are in harmony with the body, developed in the history of martial art and wild violence, when harmony could be a matter of life and death. There is still the imagery of martial skills, but it is clear that fighting does not bring about any personal development and certainly no immortality or spiritual freedom.

The body has a structure of itself, Merleau-Ponty calls this structure an inborn complex, a structured bodily fundamental consciousness of what we can do. This body structure institutes the inner and outer space out of the possibilities our body has to offer and also the culture through the physical education (or hexis[38]) we receive. The phenomena appearing in this space are vibrating and changing according to the body structure and the rhythms our of body: our heartbeat, our nervous system and our respiration.

They all originate from the inner space. The movements in tàijí synchronize the rhythms of the body, this causes them more become coherent and harmonious. This body structure is not a fixed set of possible movements, it is a structure of learning to behave in relation to the different situations in the life world.

Style

The relation between the general body structure (schéma corporel[39]) and individual behavior is the style.

While we move our body structure shows itself according to a certain style. We all have our personal style of moving, which can be changed and developed. That is why a signature is individual, and people can be recognized by the way they walk or talk.

We can develop and improve our style by adopting the style of a tradition, like we do when practicing tàijí. Style introduces consistency, order and unity in our behavior. It is a way things appear to us[40], but it is also a certain way for us to deal with the world. We can recognize it in the behavior of someone else and adopt it ourselves.

What unites the ‘tactile sensations’ in the hand and links them to visual perceptions of the same hand, and to perceptions of other parts of the body is a certain style of positioning my hands, which implies a certain style of moving my fingers and in the last resort a certain bodily attitude. The body has to be compared to a work of art rather than to a physical object.[41]

A style is in itself difficult to define, but by comparing different styles we can create a kind of grid of qualities in which the specific character of a style can be compared to other ones. This way it becomes for instance clear that Chen-style forms demand a lower stance than Yang-style ones.

The dào might be called the style of all styles. It can be known but it is indescribable because it cannot be compared to any other style. One has to live it in order to know it, because it is an experience of the body.

A painting has its style that we recognize by living in it, the same holds for calligraphy and of course tàijí. All these kinds of expressive movements are a strange mixture of order and chaos, fixation and freedom, focus and carelessness. The body has its own structure, and the mind has to abandon this structure by adopting it in a certain style.

A space-less space

Another phenomenologist, Marc Richir, insists that there is a fundamental inner space, where our hidden feelings and untamed intuitions float[42].

This is a space-less space, it is pure depth, space that has no front or back, left or right. It is the necessary condition for our physical space. It is like a kind of blood that nourishes the flesh of the world. It reveals itself in our proprioception. The body is influenced by wild essences appearing in this space, or perhaps they should be called wild metaphors. They can however made transparent and turned into pure playfulness.

It is this space that enables us to abandon the body and its structure, because of this we are our body by being separate from it. This would be the work area of nei gong 內功, because it is the target of all self-technique, a place where ataraxia or peace of mind is within reach.

Why immortals have to die

To summarize, we have first considered the martial functioning of tàijí and concluded that the use of it as an art of self-defense is limited. In real life it has more value as a self-technique.

It is a product of the Chinese culture, but it has positive effects on the well-being and health of any human being, because it improves the physical condition.

It is a way to deal with violence. Violence in its many forms is part and parcel of human existence in general. Violence has been symbolized by sports in various ways, which is the reason why sports stir up a lot of emotions. In a fight emotions are put aside, because the opponent is seen as an object. In the practice of tàijí the object is put aside and this makes it a self-technique.

This cannot be completely understood in a rational or scientific way, we have to address a deeper level of human existence and this is what Merleau-Ponty called the flesh of the world. On this level the body as well as time and space have the non-linear open structure characterized by repetitions without original. The body adapts to the flesh of the world by its style. Style is the way individuals deal with the general possibilities that are in reach. All this can easily be recognized in the practice of tàijí.

The stronger your concentration, the higher your spirit will be

One question is still remains open: how can it be possible to achieve immortality or enlightenment (tian ren rong ti 天人同 體[43]) through the practice of tàijí?

In order for this to be possible it is necessary to take the body out of the ordinary time, it has to show itself as the flesh of the world.

The stronger your concentration, the higher your spirit will be.[44]

It is clear that the martial skill is in this case just a means to achieve a higher end. This concentration must have the structure of the endless repetition without original.

There is no way someone can end the repetition by taking an immortality pill and reside forever on the mountain peaks, boring himself to immortality.

Concentration does not involve discipline here, it not the will to forcefully drive all distraction out. It consists of relaxation, releasing all disturbances. Just like in the dàoïst meditation called sitting in forgetfulness (zùowàng 坐忘).

You need your ordinary body to do this, and you need something to forget.

If there would be a way to transform this body into some eternal substance, the new body would not be able to meditate or practice tàijí. The ordinary body needs to die, but before that happens the master will repeat his immortality time and again.

How the martial skill relates to the nonviolent release of tension remains a subject for further investigation.

- Adorno, Theodor W. (1950). The Authoritarian Personality, Studies in Prejudice Series, Volume 1. New York: Harper & Row

- Allen, Barry (2015). Striking beauty. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Bahktim, Michael M. (1968). Rabelais and his world. Boston: M.I.T. (tr. Helene Iswolsky)

- Baudrillard, Jean (1970). La société de consommation. Paris: Denoël

- Bourdieu, Pierre (1994). Raisons pratiques. Paris: Ed. Du Seuil

- Csíkszenmihályi, Mihály (1990). Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. New York: Harper and Row

- Csíkszenmihályi, Mihály (2014). Flow and the Foundations of Positive Psychology. Dordrecht: Springer

- Despeux, Catharine (1981). Tàijí quan art martial, technique de longue vie. Paris: Guy Trédaniel

- Dodd, James (2018). Phenomenological Reflections on Violence. New York: Taylor & Francis (CAM) Epub.

- Feyerabend, Paul (1993). Against Method. New York: Verso

- Foucault, Michel (1990). The History of Sexuality: An Introduction. New York: Vintage Books

- Foucault, Michel (1994). Dits et Écrits IV 1980-1988. Paris: Gallimard

- Adam D. (2006). Taijiquan and the search for the little old Chinese man: understanding identity through martial arts. New York: Palgrave Macmillan

- Hansen, Chad (1992). A Daoist theory of Chinese thought: a philosophical interpretation. New York: Oxford U.P.

- Hong, Youlian (2008). Tai Chi Chuan, State of the art in International Research. Hong Kong, Karcher

- Hoogcarspel, Erik (2005). The central philosophy, basic verses. Amsterdam: Olive Press.

- Hoogcarspel, Erik (2016). Phenomenal emptiness. Charleston: SC.

- Husserl, Edmund (1973). Teleologie. Husserliana 15. 378 ― 386. Den Haag: Martinus Nijhoff

- Husserl, Edmund (1986). Phänomenologie der Lebenswelt, Ausgewälte Texte II. Stuttgart: Reclam.

- Husserl, Edmund (1993). Logische Untersuchungen. Tübingen: Max Niemeyer Verlag

- Husserl, Edmund (1996). De Krise der europäischen Wissenschaften und die transcendentale Phänomenologie. Hamburg: Meiner Verlag

- Kant, Emmanuel (1922). Kritik der Urteilskraft. Berlin: Bruno Cassirer.

- Liao, Waysun (1990). Taichi Classics, Boston: Shambhala

- Locke, John (1999). An Essay concerning human understanding. Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University.

- Marratto, Scott L. (2012). The intercorporal self. State University of New York Press

- Marteleare, Patricia de (2006). Taoism ― The road not to follow ― Amsterdam: Ambo

- Merleau-Ponty, Maurice (1945). Structure du comportement. Paris: PUF

- Merleau-Ponty, Maurice (1953). Phénoménologie de la Perception. Paris: Gallimard.

- Miller, Rory (2011). Facing Violence: Preparing for the Unexpected. Boston: Ymaa Publication Center

- Phillips, Scott Park (2016). Possible Origins. California: Angry Baby Books

- Pietrobon, Xavier (2012). L’équilibre des opposés. Paris: Université de Paris Ouest Nanterre

- Rabelais (1964). Paris: Gallimard (tr. Jacques LeClerq. 1964. The Heritage Press)

- Raposa, Michael L. (2003). Meditation and the martial Arts. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press

- Richir, Marc (1992). Méditations Phénoménologiques. Grenoble: Millon.

- Richir, Marc (2010). Variations sur le sublime et le soi. Grenoble: Millon.

- Sartre, Jean-Paul (1943). L’être et le néant. Paris: Gallimard

- Sartre, Jean-Paul (1983). Cahiers pour une Morale. Paris: Gallimard

- Sartre, Jean-Paul (1985). Critique de la Raison Dialectique II. Paris: Gallimard.

- Shamar, Meir. (2008). The shaolin Monastery. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

- Slingerland, Edward (2014): Trying not to try. Edinburg: Canongate

- Verissimo, Danilo Saretta (2012). Bulletin d’analyse phénoménologique VIII 1 (http://popups.ulg.ac.be/bap.htm)

- Wacquant, Loïc (2005): Canal Connections: On Embodiment, Apprenticeship, and Membership. Qualitative Sociology, Vol. 28, No. 4, Winter (2005). (Springer Science + Business Media, Inc.), p. 445-474

- Wile, Douglas (1996). Lost t’ai-chi classics from the late Ch’ing Dynasty. Albany: SUNY Press

- Yang, Jwing-Ming (2001). Tai Chi Secrets of the Yang Style Chinese Classics, Translations, Commentary. Boston: Ymaa Publication Center

Notes

[1] Rabelias 1964: 217-219 (I have observed that the pleasure-twats of women in this part of the world are much cheaper than stones, therefore the walls of the city should be built of twats.)

[2] Foucault 1982: 783

[3] Lees meer over Chinese-MMA-fighter Xu

[4] http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-39853374

http://shanghaiist.com/2017/06/27/shanghai-fight-stopped.php

[5] Despeux 1981

[6] Read more about Chinese Martial Arts

[7] Hong 2008

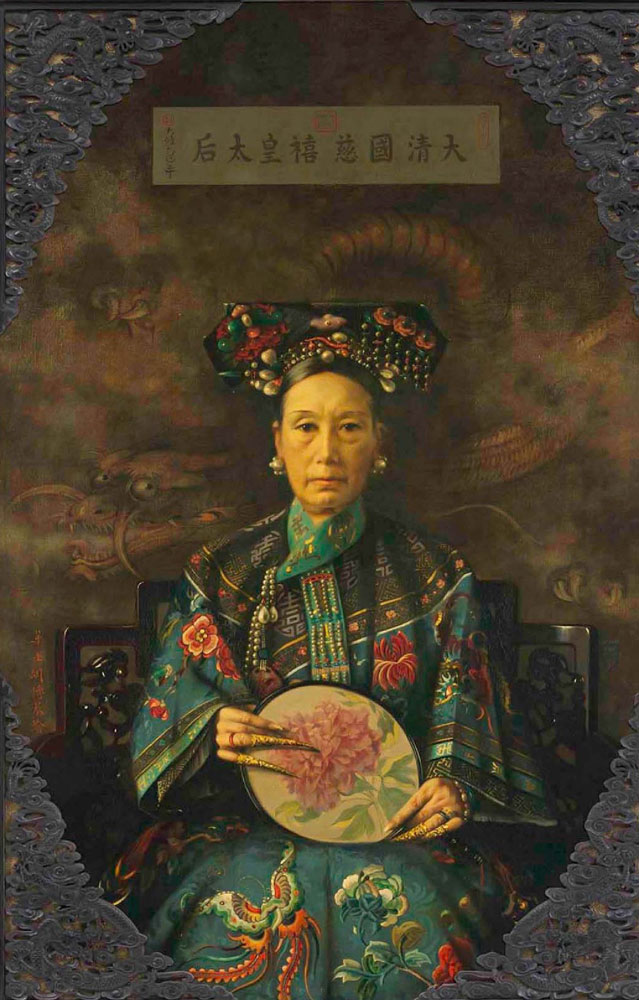

[8] Source in the Public Space of an oil painting of Empress Dowager Cixi -by Court painter Hubert Vos (1855–1935); Collection Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, United States; Source/Photographer Seed, John, Jan/Feb 2015.

[9] Aronson 1987: 54

[10] Sartre 1985: 29 … one will easily understand that the boxing sport as a whole is present in every moment of the fight as a sport and as a technique, with all human qualities and all required physical conditions (training, health conditions, and so on). Therefore one has to understand that the public has come to see beautiful boxing which the organizers try to provide (successfully or not). … Boxing is present, as a hexis, as a technique and as something everyone every time invents anew.

[11] Read more about Chinese-MMA-fighter-Xu

[12] Rory 2011: Section 5

[13] Allen 2015: loc. 396,6/690

[14] Wacquant 2005: 458

[15] Sartre 1960: 166

[16] Bourdieu 1994: 107-120

[17] Sartre 1943: 298

[18] Read more on Sartre

[19] Sartre 1983: 179

[20] This is the classical phenomenological method, in the U.S.A naturalized phenomenological discourses have been developed, for instance by Francisco Varela et al.

[21] Husserl 1993: 170

[22] Dodd 2018: Epub, loc. 142,2

[23] See on YouTube Grasping the Bird’s Tail

[24] Read more on Phenomenological reduction

[25] Locke II, 9, 2

[26] Source in the Public Domain of Edmund Husserl (circa 1910); Source http://www.gettyimages.co.uk/detail/news-photo/portrait-of-the-austrian-naturalized-german-philosopher-and-news-photo/141555173 Author Unknown (Mondadori Publishers).

[27] Husserl 1996

[28] Read more on Daoism and Zhuangzi

[29] Gewiß ist physeos odos eis physin eine Weise des Hervorkommens in die Anwesung, in der das Woher und Wohin und Wie der Anwesung dasselbe bleibt. Die physis ist Gang als Aufgang zum Aufgehen und so allerdings ein In-sich-zurück-Gehen, zu sich, das ein Aufgehen bleibt. Das nur räumliche bild des Kreisens reicht wesenhaft nicht zu, weil dieser in sich zurückgehende Aufgang gerade aufgehen läßt Solches, von dem, zu dem der Aufgang je unterwegs ist. (Martin Heidegger: Wegmarken, Klosterman Frankfurt 1978, pp. 291 (363) See also Mark Richir: Au-dela du renversement copernicien, Nijhoff, Den Haag 1976 pp. 94-95

[30] See on YouTube White crane spreads its wings

[31] In the Forty Taichiquan treatises chapter 14 it says: The understanding is the core while the martial art is the application (wén zhê tî yê wû zhê yòng yê 文者體也武者用也)

[32] Yang 2001, p. 81

[33] Read more on Ataraxia

[34] Read more on Maurice Merleau-Ponty

[35] Merleau-Ponty 1945: 239. Il va falloir de la même manière réveiller l’expérience du monde tel qu’il nous apparait en tant que nous sommes au monde par notre corps, en tant que nous apercevons le monde avec notre corps. Mais en reprenant ainsi contact avec le corps et avec le monde, c’est aussi nous-même que nous allons trouver, puisque, si l’on perçoit avec son corps, le corps est un moi naturel et comme le sujet de la perception.

[36] Merleau-Ponty 1945: 216 L’identité de la chose à travers l’expérience perceptive n’est qu’un autre aspect de l’identité du corps propre au cours des mouvements d’exploration, elle est donc de même sorte qu’elle: comme le schéma corporel, la cheminée [un objet quelconque]est un système d’équivalences qui ne se fonde pas sur la reconnaissance de quelque loi, mais sur l’épreuve d’une présence corporelle.

[37] Merleau-Ponty 1953: 182-183.

[38] Hexis (Greek) or habitus (Latin) is found among others in the Categories of Aristotle and means disposition in general; in contemporary sociology it means physical disposition, the way someone lives his body.

[39] In 1911 neurologist Henry Head suggested that our bodies possess an unconscious fixed structure that enables us to manipulate it without error, for instance we automatically scratch where it itches and we can eat with our eyes closed. Merleau-Ponty showed that this structure is not a fixed plan, but the way our body is in constant dialogue with itself and the objects in its vicinity.

[40] Merleau-Ponty 1953: 378.

[41] Ce qui réunit les ‘sensations tactiles’ de ma main et les relie aux perceptions visuelles de la même main comme aux perceptions des autres segments du corps, c’est un certain style des gestes de ma main, qui implique un certain style de mouvement de mes doigts et contribue d’autre part à une certaine allure de mon corps. Ce n’est pas à l’object physique que mon corps peut être comparé, mais plûtot à l’oeuvre d’art. (pp. 175-179)

[42] Richir 2010: p. 212.

[43] Yang 2001, p. 64.

[44] Yang 2001, p. 160.