Hans van Rappard

7 ― From: Rappard, H. van (2009). Walking Two Roads ― Accord and Separation In Chinese and Western Thought. Amsterdam: VU University Press. Chapter 3, pp. 73-86.

Enriched edition with illustrations and with the author’s permission.

part 1 – part 2 – part 3 – part 4 – part 5 – part 6 – part 7 – part 8 – part 9 – part 10 – part 11 – part 12 – part 13 – part 14 – part 15 – part 16 – part 17

Self as activity centre

When trying to sit quietly, an endless stream of mental contents was seen passing through. Yet, in spite of the continuous change of these materials the chair-sitter is likely to have felt that he or she remained the very same person at every fleeting moment of the stream.

In spite of incessant change one never stopped feeling like being the same psycho-physical unity. As pointed out by a host of thinkers, it is this feeling of unity that gives a particular stream of consciousness, or ‘you’ if you please, a distinct quality of uniqueness.

Indeed, the accessible thoughts and other mental contents are felt to be one’s own and one would be considered to be in need of treatment if one felt differently about them.

As William James introspected,

“Every thought tends to be part of a personal consciousness … My thought belongs with my other thoughts, and your thought with your other thoughts. Whether anywhere in the room there be a mere thought, which is nobody’s thought, we have no means of ascertaining, for we have no experience of its like.

The only states of consciousness that we naturally deal with are found in personal consciousnesses, minds, selves, concrete particular I’s and you’s …

It seems as if the elementary psychic fact were not thought or this thought or that thought, but my thought, every thought being owned.”[1]

Many thinkers have tried to account for this everyday experience, so many in fact that we cannot hope to treat this topic with anything remotely approaching closure. The concepts that are mobilised in Western thinking to explain the feeling, so familiar, yet so mysterious, that we keep the same identity in the midst of change, are self, I or ego, subject, and person.

Although they are often used interchangeably, person is the most comprehensive of these concepts because it tends to cover both the mental and the bodily side of the identity problem. The other concepts do not; therefore, selves, ego’s, and subjects may to some extent be thought of as persons without bodies.

As mentioned, much has been written about these concepts and many interpretations from many different angles have been proposed. To complicate the matter further, the entire cluster of concepts may be used at various levels, ranging from philosophy and theology to psychology and common sense. At the top of the scale, the philosophical/ theological self is found, which is often conceived of as an unchanging ‘bearer’ of the mental stream which somehow achieves its unity; in other words, a subject, or, in theological contexts, a soul.[2]

The bottom of the scale, where the domain of psychology and common sense is found is often called the empirical self since the incessant stream of consciousness is to some extent accessible to us.

The problem of unity – being versus change/ becoming

In a number of, mostly historical, cases the problem of unity versus change was phrased using the distinction between substance (derived from the Latin words sub and stare, literally ‘to stand under’) and quality. Following this line of thinking, the mental qualities that develop and change over one’s lifetime are assumed to belong to something that underlies or stands under them and does not change itself. That is, you and I remain you and I as substantial selves even if our mental make-up should change markedly over time or our memories fade away.

The substance-quality way to put the problem of continuity and change may ring a bell. In ancient Greek thinking a similar problem formed the focus point of much, if not most philosophical activity. I am referring to the problem of the relation between being and becoming, between the ever-changing world of the senses and the metaphysical world of permanent essences and ideas. Along similar lines, the substantial self may be understood as a metaphysical self, which in contradistinction to the mental qualities is not empirically accessible.

But I return to the empirical self, described by William James as

“the consciousness [remaining]sensibly continuous and one …

The natural name for it is myself, I, or me.”[3]

Many thinkers have construed the self as a centre of organisation, making for consistency and continuity in what otherwise would be a kaleidoscope of mental materials and processes. Think for an example of the ‘ego’ in Freudian psychology, continuously engaged in maintaining a precarious balance between the demands of society represented by the ‘superego’, and on the other hand the soaring drives of the unconscious ‘id’.

Another example will be treated below. For the moment we may think of the self and its colleagues in terms of a relatively stable centre of organisation, which makes for continuity and unity in the stream of mental events and which must be situated somewhere between the high metaphysical and the low empirical level of the scale.

As mentioned, an immense amount of literature has been written on such an intriguing human problem as the self or personal identity, especially since at its highest, or if you prefer deepest philosophical and theological layers it touches on the human soul.

And again it must be said that we cannot hope to do justice to the enormous range of viewpoints pertaining to the subject ― and neither should we try. What is required for present purposes is not a review of the literature for its own sake but rather a yardstick to appreciate the difference between the key ideas on the topic that have emerged in Western and Chinese thought.

Definition of the ‘person’

The definition of the ‘person’ proposed by the German psychologist William Stern would seem to fit the job. The term person is derived from the Latin word for theatre mask, persona[4], which gradually came to be extended to the actor wearing the mask, then to his role, and finally it took the more general meaning of our ‘personal’ role in life.

But it was not until early modern times, that is, from about 1600 onwards, that individuality, rationality, and substantiality emerged as the central features of the person, even if the last one has worn off again. Nowadays we are not much inclined to think of ourselves in terms of a substance with all its metaphysical overtones but on the other hand, few would want to deny their rationality and probably even less their individuality.

We now turn to the definition of the person proposed by William Stern (1871-1938). A pioneer of, among other fields, psychological testing (he coined the IQ concept), Stern fled the Nazis to the United States, where he published General psychology (1935).

His definition of the person ran as follows,

“The person is a living whole, individual, unique, striving towards goals, self-contained and yet open to the world around him: he is capable of having experience.”[5]

Elsewhere he had written that by virtue of its wholeness every person is something that exists independently, and also that it is something that is active from within itself.[6]

Intentional, goal-directed

It is particularly relevant in the present context that the person is goal-directed. In this regard, Stern also used the term ‘activity centre’ (Aktivitätszentrum). In other words, the person is conceived of as a centre, more specifically as the starting point of its goal-directed, intentional activity. Moreover, it is the activity centre that initiates a relation with the world in which, Stern stressed, both the person and its world are formed.

“The personal world is at all times both the destiny and the product of the person.”[7]

Thus, even if Stern conceived of the person-world relation as an oscillation between intention and response, the result is a person-oriented world. Although affected by his relation to the world, the person is the centre of its world ― not the world.

Clearly, modern man has come a long way since Homer.

One may wonder to what extent Stern’s concept of the activity centre could still be said to mirror our twenty-first century predicament. It dates from the 1930s and never has the world changed so much as in the second half of that century. True enough, the notion of the self has been challenged, not to say defused by many contemporary thinkers, while others do not conceive of it anymore as an entity within people, as did Stern, but in terms of relations between people. But these are conceptual matters.

How do we actually think of ourselves? Don’t we all think or, probably more pertinent, feel ourselves to be activity centres? Don’t we all feel that it is we, who, from within ourselves, initiate our well-reasoned goal-directed activity at the world? Don’t we all feel that we are unique individuals, separate from the world? Just consider these questions, sitting quietly in an easy chair, and on getting bored take the daily paper or a glossy magazine and go through the advertisements and examine to what kind of person they appeal to.

Inwardness and the reflective stance

Even if it was formulated more than seventy years ago, Stern’s definition of the person and especially his concept of the activity centre comprise crucial aspects of the current Western notion of the self. But there is one aspect that has not yet received much attention ― an aspect that is important in the context of this essay because initially it was unique to Western man.

The sense of self as a being with an inner depth

I am referring to what Charles Taylor[8] has called the sense of self as a being with an inner depth. It is this sense, this ‘inwardness’ that virtually constitutes our modern notion of the self.

This notion did not suddenly fall from the sky at a particular moment in the past but emerged in the course of a long historical development. Recall that it was impossible for Homer to conceive of the human body as a separate entity possessing a soul. Indeed, there are no words to be found in his epic that refer to something remotely similar to mind in the sense of a locus or centre where our thoughts and feelings are assumed to occur and get organised. Rather, Homeric man appears to have been a fragmented being whose mental activities took place in different parts of the body and whose body was variously referred to as limbs, skin, etc.

‘Order’ linked to reason

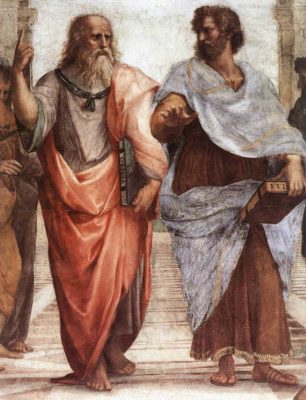

It is worthy of note that the fragmentation of the Homeric hero’s entails that they were structurally incapable as it were to act in a rational way. This is so because obviously reason cannot guide a fragmented soul, that is, an unordered mass of mental activities. It was not until Plato that ‘order’ became linked to reason. But order also received an extended meaning and came to refer to the natural or cosmic order. Platonic reason is therefore intimately linked to the natural order. This was a highly significant development. Indeed, it is the assumption of a cosmic order, that is, an order existing outside of us that serves as the starting point for our seven-league journey towards inwardness.

By virtue of its being natural, the cosmic order is also considered to be the right order and thus, ‘to be ruled by reason’ came down to a correct understanding of this order. In other words, to live rationally, which may be called the central tenet of Greek philosophy, is a matter of understanding the cosmic order and letting oneself be guided by this understanding. Therefore, a correct vision was of the utmost importance. It was inconceivable for Plato that one was ruled by reason and yet be wrong about the cosmic order because it was only there that one could see that everything is ordered for the good. The natural order, manifesting the idea of the good is the final good, worthy of being desired and sought. The good, virtuous life thus pertains not just to the order in our souls but also and more fundamentally to the good order of the cosmic whole. Therefore, the basis for virtue is the perception of this order and all that this requires is turning the soul in the right direction. Not what happens in the soul but

“where it is facing in the metaphysical landscape is what matters.”[9]

In other words, wisdom or being ruled by reason is not a function of an inner self but of something external to us, that is, the cosmic order, which is also the moral order.

The cosmic order is also the moral order

This is of course, putting it mildly, an extremely brief and partial review of what according to many thinkers is the grandest philosophy ever conceived in the Western world.

But nevertheless, we are now in the position to summarise the emergence of inwardness, following Taylor, as a development from reason as conceived in terms of an order that is found (Plato) to an order that is made by us (Descartes).[10]

In Taylor’s arrangement the pivotal thinker in this development is Augustine to whom we will turn in a moment. It is noteworthy however, that the Western inward turn was deeply influenced too by the last school of Greek philosophy, Neo-Platonism.

Not unlike Neo-Confucianism, which arose from a synthesis of Confucianism with Daoism and Buddhism, in Neo-Platonism Plato’s philosophy was synthesised with Aristotle and Stoicism, along with Judaism and early Christianity.

The truth is only to be found in man’s inward mind

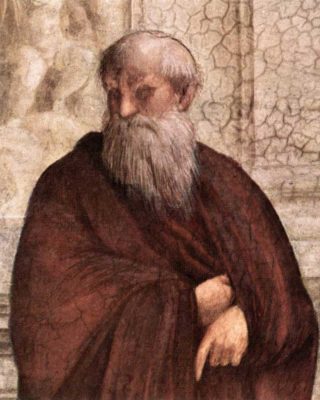

Moreover, like many other Greek thinkers at that time the founder of the school, Plotinus (205-270)[11], was well acquainted with Indian philosophy. What emerged from this vast array of concepts and beliefs was a highly influential school, which shared many ideas with Christianity, such as a marked contemplative attitude and a desire to transcend the world and establish harmony with the supreme One. Of particular importance was Plotinus’s belief that the truth is only to be found in man’s inward mind.

This found a strong echo in Augustine. Aurelius Augustine (354-430), also known as St. Augustine, was initially attracted to various heretic and philosophical schools, Neo-Platonism being of particular importance, but in his early thirties he converted to Christianity. He established a number of monasteries and became bishop of the North African city of Hippo in 395.

Augustine took over many ideas from Plato, notably his concept of the ideas and his vision of the cosmos as a rational order. But he understood the cosmic order as an expression of the Ideas of God, which, just as in Plato but now following the Bible is also seen as organised for the good. Indeed, according to Augustine as well as Plato the cosmic order exhibits reason, while both also conceived of the good as the perception and love of it. What stands in the way of this perception, and on this score too Augustine agrees with Plato, is the human preoccupation with the sensible world, which after all is but the superficial and fragmented manifestation of the higher reality of the good order. And again as in Plato, the human soul must in the Augustinian view be turned around into a new direction.

Painted in such broad strokes there is a lot of continuity between Plato and Augustine but of course there are also many differences.

Opposition lower world of the senses versus higher world of the rational order

One of these differences, whose significance can hardly be exaggerated concerns the opposition of the lower world of the senses and material things to the higher world of the rational order. The crucial point is that in Augustine this opposition is described for the first time in terms of inner ― outer. In Plato such a dichotomy is not to be found. But in Augustine the body, including the senses, is opposed as outer against the inner soul. And this way of putting things is of great importance for Augustine because

“the road from the lower to the higher, the crucial shift of direction passes through our attending to ourselves as inner.”[13]

In a saying that has become particularly famous Augustine exhorts us,

‘Do not go outward; return within yourself. In the inward man dwells the truth’.

For present purposes the emergence of the inner world can be traced to the diminished significance of the cosmic order out there. In Plato the truth, that is, the rational order in the cosmos may be found by turning towards the ideas. This involves a struggle that most human beings are incapable of bringing off, but ultimately it just concerns the direction of our attention, and that direction is outward. For Augustine too, it is well nigh impossible to contemplate the truth. But in his view God is not only the principle of the cosmic order but first and foremost of our mental activity.

This is so, Taylor says, because the Augustinian God is

“what powers the eye which sees. So the light of God is not just ‘out there’… it is also an ‘inner’ light.” As Augustine himself put it,

“there is one light which we perceive through the eye, another by which the eye itself is enabled to perceive; this light by which [outer things]become manifest is certainly within the soul.”[14]

Interior master

The light in the soul is God, who has thus become our ‘interior master’. It goes without saying that we are not likely to find an interior master outside of us but only in the inward man and that we must therefore turn in that direction. What this monumental change comes down to is that Augustine shifted the focus from the truth as something that may be known (the cosmic order) to the activity of knowing (the light in the soul).

It will be seen shortly that this shift had far-reaching consequences because, as Taylor put it

“to look towards this activity is to look to the self, to take up a reflexive stance.”[15]

To ‘look to the self’ was not an entirely new idea. Reflection can be found in many ancient thinkers who counselled their students to be less concerned with wealth, power, and pleasure and spend more attention to their souls instead. But Augustine introduces a new type of reflectivity, which Taylor calls ‘radical’ reflection.

Radical reflection

It is important to be clear on the difference between the two types. It is one thing to turn one’s attention to oneself in a simple way as, for instance, remembering something.

But it is quite another thing to focus on the experience-of-remembering-something and this is what was made possible by Augustine’s emphasis on the activity of the mind.

To stay with the example, in the latter case we do not just focus on a memory ― a mental object ― but on the activity of memorising. In other words, we experience our experience and, in contradistinction to the external perception by the senses, this ‘interior sense’, by virtue of it being immediately present to itself leaves no room for doubt. It is immediately and indubitably evident.

Now, Taylor argues, and here we must be prepared to make a big leap, those who have been brought up in the Western world have come to understand such an experience-of-experience as the experience-of-someone.

In other words, while we can be engrossed in a memory-image (a mental object) without thinking of it as ‘my’ memory, in the case of an experience-of-experience (a mental activity) it proves somehow difficult not to think in terms of ‘my’ experience; the activity is felt to be ‘mine’.

The first-person perspective

It would be hard to overrate the importance of this familiar observation because it entails a first-person point of view ― a subjective perspective in which I make my own experience my object of experience. Usually we are simply focused on the things that we experience. But we can also turn our attention around and focus on the experience itself, that is, we can

“try to experience our experiencing, focus on the way the world is for us.” Thus, radical reflection is “a kind of presence to oneself”, which modern man cannot separate from experiencing himself as its ‘agent’.[16]

However obvious the first-person stance now seems to us, it was not obvious to the ancient Greeks. Neither was it obvious to the Chinese, who seem to have been particularly ill-equipped to develop such notions. The first-person perspective, the modern notion of being an I, ego, or self, the experience of oneself as ‘I am’ did not begin to emerge in the Western world until Augustine’s introduction of inwardness entailed by radical reflectivity. This introduction was a fateful one, Taylor observes,

“we have certainly made a big thing of the first-person standpoint … to the point of aberration, one might think. It has gone as far as generating the view that there is a special domain of ‘inner’ objects available only from this standpoint; or the notion that the vantage point of [Descartes’] ‘I think’ is somehow outside the world of things we experience.”[17]

Augustine’s treatment of the will

This quotation provides a useful preview of the themes that will follow in the remainder of this section. But before we leap more than a millennium to Descartes, I will make a brief excursion to Augustine’s treatment of the will. The reason why I want to make this excursion is that the muscle-consciousness that was a unique aspect of medicine in ancient Greece did to some extent contribute to the emergence of the idea of an autonomous will.

Thematic connection between musculature, will, and agency/ self

The new interest in the muscles, called by Galen the organs of voluntary motion, was linked to a rudimentary notion of the agency of the self. What was found, in other words, is a thematic connection between musculature, will, and agency/ self. The will constitutes another point where the ways of Plato and Augustine parted.

The difference can be understood if it is recalled that both assumed that the cosmos was ordered for the good and that the human soul should therefore turn its attention towards it. But Plato and Augustine differed in that according to the former the direction of our attention was determined by how much of the (outer) good is perceived, whereas for Augustine it depended primarily on the (inner) light of the soul. Thus, although the Stoics had already developed an influential notion of the importance of the will as choice in moral questions, the main source of Augustine’s treatment of it was the Christian view of the will as the core of the human being. Will was even involved in cognition since it

“depended on attention, an ‘intentio animi’, a direction of the mind … Because a man can control his attention, he is master of his first thoughts; by exercising will he can acquire discipline and control over them, given the grace of God.”[19]

But in such a view ill will, that is, attention turned in the wrong direction cannot be explained by a simple lack of knowledge. To Augustine it is a perversity, a disposition

“to make ourselves the centre of our world, to relate everything to ourselves, to dominate and possess the things which surround us.”[20]

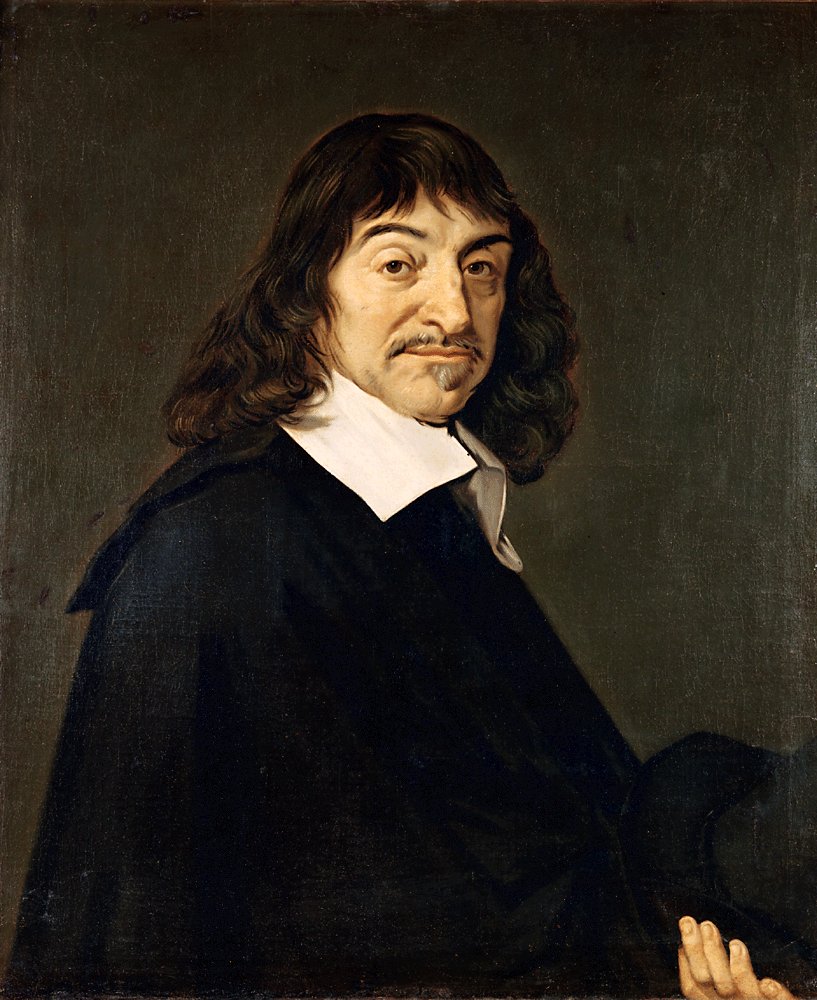

Descartes: second inward turn

As will be elaborated shortly, this perversity fits nicely ― or perhaps unpleasantly ― into the condition of modern man. But first we must turn to Descartes, our third man so to speak, in the long but inexorable shift from ‘outer’ to ‘inner’ reason.

Truth is, and remains, squarely rooted in the inner self

On first sight the story seems to repeat itself: just as Augustine took over many ideas from Plato but radically changed them, Descartes (1596-1650) in his turn took over many ideas from Augustine but altered them along at least as radical lines. This significant episode in the history of Western thought can be summarised schematically by saying that although the Augustinian way leads through our inner being it ultimately brings us to a truth that exists outside of us (God), but that the Cartesian way leads inward to a truth that is, and remains, squarely rooted in the inner self. This second inward turn would probably have been inconceivable without the rise of early modern science to which Descartes contributed heavily as a philosopher and mathematician.

The development of what we now call the natural sciences, initially at the hands of astronomers and mathematicians like Copernicus, Kepler, Galileo, and others, brought with it that the cosmic order could no longer be seen as embodying ideas because it came to be understood as a huge mechanism. Mechanistic metaphors, notably clockwork, became extremely influential. Of course, the new mechanistic world view also had a bearing on the view of man and it was not long before human beings began to be conceived of as machines, albeit still with a ‘ghost inside’. Understandably, this view completely severed the ancient vision of a relation between the good moral life and knowledge of the cosmos. The cutting’ of this link had a drastic effect on the traditional view of what it meant for human beings to be ruled by reason.

Modern science based on ‘correct representations’

In the discussion of science in ancient Greece the notion of representation was alluded to. In the wake of emerging modern science however, representations assumed a tremendous importance because to know reality became equivalent to having correct representations (also called ideas), or mental pictures-of-things-in-the-world.

And since these pictures were assumed to be somehow located in the mind the representations functioned exactly as suggested by their name, namely as representations-in-the-mind of things-outside-the-mind. What this means is, simply put, that I don’t see the tree in the garden but only the idea or picture representing that tree in the mind. Curiously, knowledge thus became fundamentally self-knowledge.[22]

The mind was completely shut off from the world (and from the body for that matter) and was thought to be only capable of getting in touch with the representations ― but emphatically not with the things in the world. It is easy to appreciate that an understanding of the cosmos as a self-revealing reality could not but be abandoned.

The constructive dimension of the Modern mind

However, once the ancient and deeply rooted notion of a cosmic order, existing outside of and independent from humans is rejected, it is conceivable that the need may make itself felt to construct an alternative order; an order that is acceptable to the scientific mind. And this is what happened ― the modern mind assumed a constructive dimension. When the representations (ideas) were assigned a mental and thus fully internal status,

“the order of ideas ceased to be something we find and became something we build.”[23]

But how was a new order to be built? Since the representations had become purely mental entities the outside world that they were thought to represent could not function anymore as the criterion for their order. Therefore, although paradoxical at first sight, it is actually quite logical that the criterion formulated by Descartes further strengthened the internal status of the representations. He guaranteed their order by their certainty, their subjective certainty that is, generated by what he called their ‘clear and distinct perception’.

In other words, the criterion for the order of the representations that the knower constructs in his mind, is derived from the activity of that very mind itself. Once more it is seen that knowledge had virtually become self-knowledge, that is, knowledge of the knowing self constructed by itself. Consequently, every window on the world that the mind possessed had been firmly boarded up.

Disengagement from the world

Another way of putting this is that the Cartesian man had now fully disengaged himself from the world. Descartes’ monumental move, which would not have been possible without Augustine, further fortified the reflective stance. We, modern men, Taylor writes, have

“to turn inward and become aware of our own activity and of the processes which form us. We have to take charge of constructing our own representation of the world … Disengagement demands that we stop simply living in the body or within our traditions or habits and, by making them objects for us, subject them to radical scrutiny and remaking. Of course the great classical moralists [such as the Hellenistic philosophers treated in chapter five]also call on us to stop living in unreflecting habit and usage. But their reflection turns us towards an objective order. Modern disengagement by contrast calls us to a separation from ourselves through self-objectification. This is an operation which can only be carried out in the first-person perspective … It calls on me to be aware of my activity of thinking or my processes of habituation, so as to disengage from them and objectify them. This vision is the child of a peculiar reflexive stance, and that is why we who have been formed to understand and judge ourselves in its terms naturally describe ourselves with the reflexive expressions which belong to this stance: the ‘self’, the ‘I’, the ‘ego’.”[24]

Triumph of the quest for certainty over the quest for wisdom

With regard to Chinese and Greek philosophy as ways of life, which will be discussed in the next papers it is worthy of note that Rorty concluded that the Cartesian change

“from mind-as-reason to mind-as-inner-arena was not the triumph of the prideful individual subject freed from scholastic shackles so much as the triumph of the quest for certainty over the quest for wisdom …

Science, rather than living, became philosophy’s subject.”[25]

Clearly, a cleft had been forged, opened up by Augustinian inwardness, widened enormously by Cartesian reflectivity and disengagement, and finally taking the form of the modern self as a self-enclosed entity, a container as it were, brimful with representing thoughts. It is entirely obvious to us that these representations are located ‘in’ the mind,

“as an inner space in which [they pass]in review before a single Inner Eye.”[26]

Whereas the ancients situated them in the (external) cosmos, to us our thoughts and feelings are confined to our (internal) disengaged minds. This explains, incidentally, why what we now call psychology was impossible to conceive for the Chinese (paper 4) and would not have been possible to conceive in the West prior to Descartes, quite apart from the social and scientific developments that have determined its specific shape since the late nineteenth century.

The opposition of subject and object

The boarding up of the modern mind also prompted a new understanding of the notions of subject and object, where both came to be thought of as independent of each other. In current social and political views disengagement comes to the fore as individualism, while another consequence may be found in the clear-cut boundary that is assumed to exist between the mental and the physical. The opposition of subject and object is of course the flip side of the modern view that representations are located in the mind. Put differently, the related views of the closed-up, disengaged self and the independent subject lie at the basis of a number of dichotomies and oppositions that never occurred to the ancient Greeks and neither, to the Chinese.

Looking back at some twenty five centuries then, it appears that the Western mind has essentially lost its touch with the external world as it were. Gradually severing its link with the cosmic order it has ever deeper withdrawn into itself, in the process creating for itself the privileged position of being the centre of command where all missions are planned and monitored but where no dirty hands need or indeed can be made since the theatre of operations exists only as represented by maps on the walls.

At this point it may again be asked if Stern’s concept of the activity centre is applicable to the modern predicament? Yes, I think it may still be used with regard to the modern self as sketched above. Actually, in Taylor’s broad historical strokes what was said about Stern’s conception has become more elaborate, enriched by notions as inwardness, reflectivity, and disengagement.

But, one might object, wasn’t Stern’s activity centre in touch with the external world, whereas in Taylor’s updated view the self was pictured as effectively insulated against it? But this objection is not pertinent since, as observed above, Stern’s activity centre creates its world rather than the world. Thus, even if their views are separated by more than half an eventful century in both Stern and Taylor it is the modern self that moves the world ― not the other way round, and it does so at the price of being “out of tune” with the world.

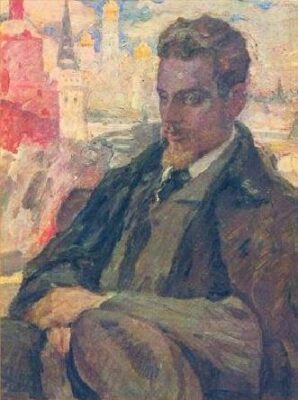

Poetical words on the enclosed self

But Wordsworth is not the only poet who may be referred to at this juncture. Taylor draws the attention to Rainer Maria Rilke, who, one and a half centuries later in his Seventh Elegy used much harsher words on the enclosed self,

Nowhere, beloved, will world be but within us. Our

life passes in transformation. And the external shrinks

into less and less. Where once an enduring house was,

now a cerebral structure crosses our path,

completely belonging to the realm of concepts, as though it still stood in the brain.

Nirgends, Geliebte, wird Welt sein, als innen. Unser

Leben geht hin mit Verwandlung. Und immer geringer

schwindet das Außen. Wo einmal ein dauerndes Haus war,

schlägt sich erdachtes Gebild vor, quer, zu Erdenklichem

völlig gehörig, als ständ es noch ganz im Gehirne.[28]

Rainer Maria Rilke ― Die siebente Elegie

- Ames, R.T. (1994). The focus-field self in classical Confucianism. In R. Ames, W. Dissanayake, and T.P. Kasulis (Eds.). Self as person in Asian theory and practice (pp. 187-212). Albany: SUNY Press.

- Angle, S. (2003). Philosophy of governance. In A.S. Cua (Ed.). Encyclopedia of Chinese philosophy (pp. 534-540). New York:

- Chan, Wing-tsit. (1963). A sourcebook in Chinese philosophy. Princeton: Princeton U.P.

- Cheng, Chung-ying (2003b). Ti: body or embodiment. In A.S. Cua (Ed.). Encyclopedia of Chinese philosophy (pp. 717-720). New York: Routledge.

- Hearnshaw, L.S. (1987). The shaping of modem psychology. London: Routledge.

- Ivanhoe, Ph.J. (2000). Confucian moral self cultivation. Indianapolis: Hackett Publ. Co.

- James, W. (1890/1950). The principles of psychology, Vol. I. New York. Dover Publ.

- Jullien, F. (1998). Un sage est sans idee. Paris: Editions du Seuil.

- Jullien, F. (2000). Detour and access: Strategies of meaning in China and Greece (Sophie Hawkes, transl.). New York: Zone Books.

- Kates, G.N. (1967). The years that were fat: The last of old China. Cambridge (MA): MIT Press.

- Nakamura, H. (1960). The ways of thinking of Eastern peoples. Tokyo: Printing Bureau, Japanese Government.

- Nylan, M. (2008). Boundaries of the body and body politic in early Confucian thought. In D. A. Bell (Ed.). Confucian political ethics (pp. 85-110). Princeton: Princeton U.P.

- Plaks, A. (Transl). (2003). To Da Xue and Chung Yung (The highest order of cultivation and On the practice of the mean). London: Penguin Books.

- Pongratz, L.J. (1967). Problemgeschichte der Psychologie. Bern: Francke Verlag.

- Rappard, J.F.H. van (1979). Psychology as self-knowledge (Transl. Liane Faili). Assen (Neth.): Van Gorcum.

- Rorty, R. (1980). Philosophy and the mirror of nature. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Rosemont, H. (2008). Civil society, government, and Confucianism: A commentary. In D.A. Bell (Ed.). Confucian political ethics (pp. 46-57). Princeton: Princeton U.P.

- Shun, Kwong-loi (2003). Xiushen (Hsiu-shen): Self-cultivation. In A. S. Cua (Ed.). Encyclopedia of Chinese philosophy (pp. 807-809). New York: Routledge.

- Taylor, Ch. (1989). Sources of the self: The making of the modem identity. Cambridge: Cambridge U.P.

- Tu, Wei-ming (1985). Confucian thought: Selfhood as creative transformation. Albany: SUNY Press.

- Tu, Wei-ming (1994). Embodying the universe: A note on Confucian self-realization. In R.T. Ames, W. Dissanayake, and T.P. Kasulis (Eds.). Self as person in Asian theory and practice (pp. 177-186). Albany: SUNY Press.

Notes

[1] James, 1890/1950, Vol. I, pp. 225-226

[2] Read more on the history of the concept Soul

[3] James, 1890/1950, Vol. I, p. 238

[4] Read more on the concept of Persona

[5] Hearnshaw, 1987, p. 223

[6] Pongratz, 1967, p. 46

[7] Hearnshaw, 1987, p. 224

[8] Read more about Charles Taylor, Canadian philosopher and professor emeritus at McGill University (Montreal) from 1961 to 1997.

[9] Taylor, 1989, p. 124

[10] Taylor, 1989, p. 124

[11] Read more on Plotinus ― Fresco Rafael at the Raphael Rooms, Apostolic Palace, Vatican City, Detail of “The School of Athens” (1509–1511) by Raffaello Sanzio (1483–1520) Collection Apostolic Palace Rome, Italy.

[12] Source in the Public Domain of Plato ― by Rafael (1483–1520), “The School of Athens” (1509–1511) – detail of a fresco at the Raphael Rooms, Apostolic Palace, Vatican City, Italy.

[13] Taylor, 1989, p. 129

[14] Taylor, 1989, p. 129

[15] Taylor, 1989, p. 130

[16] Taylor, 1989, pp. 130-131

[17] Taylor, 1989, p. 131

[18] Source in the Public Domain of an oil painting of the 17th century: Portrait of Saint Augustine of Hippo receiving the Most Sacred Heart of Jesus ― by Philippe de Champaigne (1602–1674) Collection Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, US.

[19] Hearnshaw, 1987, p. 40

[20] Taylor, 1989, p. 138

[21] Source in the Public Domain of an oil painting of René Descartes ― by Frans Hals (1582/1583–1666)

Portrait of the French philosopher and mathematician René Descartes (1596-1650). Collection Louvre Museum, Paris, France.

[22] Van Rappard, 1979

[23] Taylor, 1989, p. 144

[24] Taylor, 1989, pp. 174-175

[25] Rorty, 1980, p. 61

[26] Rorty, 1980, p. 50

[27] Source in the Public Domain of an oil painting (1928) of Rilke by Л.Пастернак Р.Рильке в Москве

Author L.Pasternak – Source http://www.liveinternet.ru/users/2010239/post83656877/

[28] Taylor, 1989, p. 501