A philosophical view

Nivedita Yohana

Wijsheidsweb, April 4 2016

The mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation. What is called resignation is confirmed desperation. A stereotyped but unconscious despair is concealed even under what are called the games and amusements of mankind.

Henry David Thoreau

One must really have suffered oneself to help others.

Mother Theresa

Do you shy away from suffering? Are you in the eye of a storm? Franz Kafka’s short poem offers a perspective when it comes to the exquisite pain that we, mere mortals have to go through in this life. Once we’ve spent our time on Earth for a while, we ought to be wise enough than to run away from dark emotions and their attendant pain that can dwell in our hearts and minds. But it’s easier said than done but not impossible. Sometimes we build walls upon walls to prevent ourselves from experiencing life because we’re lethally afraid of having to go through the not-so-cheerful parts of it. This constant building of emotional walls offers us no real benefit except that it wears us down, keeps us chained to past hurts and miseries.

Let the words of Kafka in his short poem here light up a candle in our journey through the tunnel of darkness

You can hold back from the

suffering of the world,

you have permission to do so,

and it is accordance,

with your nature,

but this very holding back,

is the one suffering,

you could have avoided.

Franz Kafka

Life still goes on even in our darkest hours of loneliness which every man is condemned. Sometimes things don’t turn up the way we want them to be. Or that a certain part of our life is crumbling down, and we are angry, helpless and vulnerable. It is understandable to feel the immediate sensation of pain, but we have a right to return to life, living it as fully as we can, if we’d just permit ourselves to do so. Experience of survival is the key. What will the modern man do when slapped in the face with the absurdity of his own existence? Become an adventurer, passionate, serious, or intellectual? Where will his values come from when there are no values — how will he create them out of nothing? Is it easier to adopt a game full of illusions and prejudices created by someone else and compromise what we believe in and want? Most people in their attempt to please the society trade their integrity to slavery constantly trying to be someone else.

I have suffered too much in this world not to hope for another.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Simone de Beauvoir in her book The Ethics of Ambiguity forces the reader to come face to face with the absolute absurdity of the human condition, and then, proceeds to develop a dialectic of ambiguity that will enable the reader not to master the chaos, but to create with it. This book will probably alter many well-rooted philosophical perceptions — de Beauvoir uses the dramatic image of how the Nazi’s conditioned themselves to become insensitive to human suffering.

Metamorphosis: Change through awareness

In Franz Kafka’s The Metamorphosis, Gregor’s predicament is much like that of any person suffering from severe, particularly disfiguring, chronic illness or disability. Gregor’s life story and personal identity change dramatically when he becomes a vermin. In the new identity his senses are different: the hospital across the street is now beyond Gregor’s range of vision. His abilities change. Shifts in spatial arrangements circumscribe Gregor’s movements. His voice is transformed. Some of Gregor’s changes are generated from within; some are conditioned by the world’s reaction to his metamorphosis. Other metamorphoses also occur in the story. Gregor’s family sees his predicament as an affront to them (after all, they expect Gregor to support the family). They withdraw from him, try to contain the damage, but in the process, begin to change their own life stories as well — Gregor’s father, who had been disabled, mobilizes and goes back to work; he changes from being an “old man” to a bank official “holding himself very erect.” Gregor’s sister also gets a job and seems on the verge of a new life. The Metamorphosis can also be seen as a reaction against bourgeois society and its demands. Gregor’s manifest physical separation may represent his alienation and inarticulate yearnings. He had been a “vermin,” crushed and circumscribed by authority and routine. He had been imprisoned by social and economic demands: “Just don’t stay in bed being useless …”. In a psychoanalytic interpretation, The Metamorphosis prevents the imminent rebellion of the son against the father. Gregor had become strong because of his father’s failure. He crippled his father’s self-esteem and took over the father’s position in the family. After the catastrophe, the same sequence takes place in reverse: son becomes weak, and father kills him.

Why the suffering? Why me?

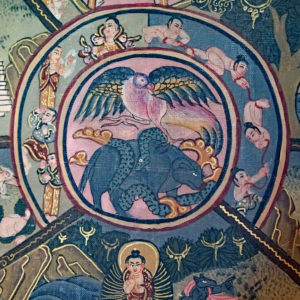

Suffering, both mental and physical, is thought to be part of the unfolding of karma and is the consequence of past inappropriate action (mental, verbal, or physical) that occurred in either one’s current life or in a past life. It is not seen as punishment but as a natural repercussion of the moral laws of the universe in response to past negative behaviour. Hindu traditions promote coping with suffering by accepting it as a just consequence and understanding that suffering is not random. If a Hindu were to ask, “why me?” or feel her circumstances were “not fair,” a response would be that her current situation is the exactly correct situation for her to be in, given her soul’s previous action. Experiencing current suffering also satisfies the debt incurred for past negative behaviour. Suffering is a part of living until finally reaching moksha. Until reaching this state, suffering is always present on life’s path. Hindu tradition holds that as we are in human form on earth, we are bound by the laws of our world and will experience physical pain. Pain is truly felt in our current physical bodies; it is not illusory in the sense of not really being felt. But while the body maybe in pain, the Self or soul is not affected or harmed. Arjuna, a seeker of wisdom in The Bhagavad-Gita, is told:

The self embodied in the body of every being is indestructible”. “Weapons do not cut it, fire does not burn it, waters do not wet it, wind does not wither it. It cannot be cut or burned; it cannot be wet or withered; it is enduring, all-pervasive, fixed, immovable, and timeless.

As the Self is not affected, there need be no concern over transient suffering. Pain and suffering are not seen as solely bad but as experiences that need to be viewed from multiple perspectives. Pain and pleasure is integral part of human life. Both are essential in equal measures for a man to evolve. Hindu traditions hold that all things are manifestations of God/The Ultimate, so nothing is only good or bad; God/The Ultimate encompasses everything. Everything, including pain and suffering, is given by God/The Ultimate. To view suffering as bad is to see only one side of it. Suffering is positive if it leads to progression a spiritual path. As the adage goes, The person who dives into the sea afflictions brings rarest of rare pearls.

Embrace suffering

Some even embrace suffering as a way to progress on his spiritual path, to be tested and learn from a difficult experience. Attachment and detachment are concepts that in Hindu traditions relate to one’s level of involvement in this world and to the power this world holds over one’s state of mind. Attachment signifies over involvement in this world, having desires for things that one does not have and clinging to things one has. Detachment is a positive state of objectivity toward this world, where relationships, objects, and circumstances hold no power over one’s state of mind. Attachment is a primary stumbling block to achieving moksha, complete release. Attachment perpetuates the “terrible bondage” that keeps a person in the cycles of samsara, rebirth. Only through recognition that the Self is not bound to this world of suffering can release be achieved. Perfect detachment creates an “… even disposition in the face of either happiness or sorrow …” When one achieves perfect detachment, no problem or circumstance, including pain, can cause one to suffer. The Bhagavad-Gita says,

Contacts with matter make us feel heat and cold, pleasure and pain. Arjuna, you must learn to endure fleeting things—they come and go! When these cannot torment a man, when suffering and joy are equal for him and he has courage, he is fit for immortality.

One part of achieving detachment is to follow dharma, appropriate action, but to be unconcerned with the outcomes of these actions. Arjuna is told:

Be intent on action, not on the fruits of action; avoid attraction to the fruits and attachment to inaction! Perform actions, firm in discipline, relinquishing attachment; be impartial to failure and success this equanimity is called discipline.

Hindu traditions need recognize that we are not in control of outcomes, nor do we know what the appropriate outcome from the perspective of karma is. To understand Buddhist treatment of suffering, one must be acquainted with four “interdependent aspects of the Buddhist world view — apart from which there is no Buddhism” — the doctrines of impermanence, non-self, and interdependent co origination, and the Law of Karma. “The first three doctrines characterize the structural character of all things and events at every moment of space time,” Dr. Paul O. Ingram of Pacific Lutheran University presents the Buddhist tradition’s treatment of the problem of suffering in his article Suffering and Buddhism — notes, “while the Law of Karma points to how human beings cause suffering both to themselves and other sentient beings.

These elements of the Buddhist world view are so interdependent that each involves the other — like spokes of a wheel — so that each one needs to be understood in light of the other three.” “The Buddha taught that all existence is duhkah, usually translated as ‘suffering’ in Western languages,” Ingram says. “But more than simple suffering is involved in this teaching … all existence involves suffering, or better, ‘unsatisfactoriness,’ because all existence is characterized by change and impermanence. Literally, everything and event at every moment of space-time — past, present, and future — has existed, now exists, or will exist as processes of change and becoming, because all things and events are processes of change and becoming. Consequently, life as such is duhkha, ‘unsatisfactory’ ‘suffering,’ physically, mentally, morally.” When “we become aware that our own lives mirror the universality of impermanence, that change and becoming are ingredient in all things, that there is no permanence anywhere; when we experience our own mortality, and feel the resulting anxiety about our lack of permanence, we have an understanding of what the Buddha was driving at in the first noble truth.” “Seeing permanence of any kind forces us to live out of accord with reality, ‘the way things really are,’” Ingram says. And as “Buddhists understand the Law of Karma, living out of accord with reality causes suffering in the numerous forms suffering can take individually and collectively.” “If there exist only process and becoming, but no permanent ‘things’ that process and ‘become,’ who or what experiences ‘suffering?’” Ingram asks. “Or put another way, if there is no ‘soul,’ who suffers?” “Hinduism, some forms of classical Greek philosophy, and traditional Christian teaching,” Ingram says, suggest “the existence of a permanent soul-entity remaining self-identical through time to explain continuity, “the paradoxical experience that we are the same person through the changing moments of our lives even as we experience that we are not the same person through the moments of our lives.” Buddhism, however, “rejects any and all notions of permanence, including the notion of unchanging self or soul entities,” Ingram says. “We are not permanent souls or selves; we are impermanent non-selves.” “Non-self,” however, does not mean “non-existence.” Rather, Ingram says, “we either exist or non-exist as a continuing series of interdependently causal relationships.” According to the doctrine of interdependent co-origination, “things, events, and us become in interdependent relation with everything in this universe at every moment of space time … we are as impermanent as the systems of relationships that constitute us.” Stated differently, Ingram says, “We are not permanent soul entities that have interdependent relationships and experiences. We are those relationships and experiences as we undergo them. We are not soul entities that suffer, we are our suffering” as we experience suffering.

Awakening

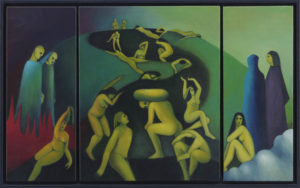

Nirvana, enlightenment, and awakened compassion. Two particular issues — and “problems” for the Buddhist treatment of suffering — are human rights and violent social activism. “through Buddhist eyes, the Western struggle for human rights seems to be a disguised form of clinging to permanent existence as in an impermanent universe,” Buddhist teaching, however, grounded in the classical Buddhist doctrines of impermanence, non-self, interdependent co-origination and the Law of Karma, faces a different challenge. Buddhist teaching explains the presence of suffering as a result of individuals attempting to cling to permanence in a fleeting universe. The difficulty for Buddhism, however, lies in how to address, from a worldview grounded in nonviolence, the suffering that results from oppression institutionalized in social systems. According to Ingram, “the issue of suffering is not approached anywhere in Buddhist thought as a ‘problem of evil,’ since, given the non-theistic character of the Buddhist world view, the problem of theodicy cannot even occur. Furthermore, Buddhist reflection on unmerited systemic suffering has occurred only within the last thirty years, mostly inspired by Buddhist dialogue with Christianity.” Ingram concludes, “All that can be said for certain in this regard is that Buddhist thought and practice on this issue are still in process.” So, we start the path to the end of suffering, not by trying to drop our clingings immediately, but by learning to cling more strategically. In other words, we start where we are and make the best use of the habits we’ve already got. We progress along the path by finding better and better things to cling to, and more skilful ways to cling, in the same way you climb a ladder to the top of a roof: grab hold of a higher rung so that you can let go of a lower rung, and then grab onto a rung still higher. As the rungs get further off the ground, you find that the mind grows clearer and can see precisely where its clingings are. It gets a sharper sense of which parts of experience belong to which noble truth and what should be done with them: the parts that are suffering should be comprehended, the parts that cause of suffering — craving and ignorance — should be abandoned; the parts that form the path to the end of suffering should be developed; and the parts that belong to the end of suffering should be verified. This helps you get higher and higher on the ladder until you find yourself securely on the roof. That’s when you can finally let go of the ladder and be totally free. Derrida writing about suffering in his article “Work of Mourning” says, that of the one who gives birth, who brings to the light of day and gives something to be seen, who enables or empowers, who gives the force to know and to be able to see-and all these are powers of the image, the pain of what is given and of the one who takes the pains to help us see, read, and think. When one works on work, on the work of mourning, when one works at the work of mourning, one is already, yes, already, doing such work, enduring this work of mourning from the very start, letting it work within oneself, and thus authorizing oneself to do it, according it to oneself, according it within oneself, and giving oneself this liberty of finitude, the worthiest and the freest possible.

One cannot hold a discourse on the “work of mourning” without taking part in it, without announcing or partaking in death, and first of all in one’s own death. In the announcement of one’s own death, which says, in short, “I am dead,” “I died”-such as this book lets it be heard-one should be able to say, and I have tried to say this in the past, that all work is also the work of mourning. All work in general works at mourning. In and of itself. Even when it has the power to give birth, even and especially when it plans to bring something to light and let it be seen. The work of mourning is not one kind of work among other possible kinds; an activity of the kind “work” is by no means a specific figure for production in general. There is thus no metalanguage for the language in which a work of mourning is at work. This is also why one should not be able to say anything about the work of mourning, anything about this subject, since it cannot become a theme, only another experience of mourning that comes to work over the one who intends to speak. To speak of mourning or of anything else. And that is why whoever thus works at the work of mourning learns the impossible-and that mourning is interminable. Inconsolable. Irreconcilable. Right up until death-that is what whoever works at mourning knows, working at mourning as both their object and their resource, work-ing at mourning as one would speak of a painter working at a painting but also of a machine working at such and such an energy level, the theme of work thus becoming their very force, and their term, a principle.

What might be this principle of mourning? And what was its force? Jean-Paul Sartre seem to have validated and solved Derrida’s questions on principle of mourning. Sartre opines that we are entirely responsible for not only what we are but also what we will be. If we look at ourselves and find that we are unhappy, or we are in circumstances which limit us, then Sartre states we have only ourselves to blame. We cannot blame our parents or teachers or friends for their influence. For, if they have influenced us, it is because we have allowed them to do so. Insofar as we allow others to influence what we really want, we are inauthentic human beings living in bad faith. We usually become this way through “trying to get along.” We do not have the moral courage to “lead our own lives” and set up our own projects. Instead, we drift from thing to thing, being “controlled,” so we think, by external circumstances.

Existentialism says, “existence precedes essence” Existence: the fact of being, the presence of something, the “thisness,” “that it is.” Essence: the kind of thing it is, the blueprint, plan, or description, the nature of the thing, “what it is.” Sartre wanted to maintain that man intrinsically has no nature. That is, he is thrown into this world, not of his own making, and is condemned to determine what he will be. In other words, our “existence precedes our essence.” We exist first and determine our essence by means of choice. If we compare this view with mainstream Christianity, it says, man’s nature comes first–man is a sinner. Consequently, here, essence precedes existence, since man is entirely subject to God’s plan or blueprint. Sartre’s views this with that of the construction of a table. The carpenter has in mind the nature of the table and works from a plan. From sawing, sanding, nailing, and so on, the table comes into existence. Hence, in this case, “essence precedes existence.” As Sartre writes, we are a plan aware of itself. “Man is nothing else than his plan: he exists only to the extent that he fulfills himself; he is therefore nothing else than the ensemble of his acts, nothing else than his life.”

Through our choices, we determine or create what we will be. In those choices, we choose according to what we believe we ought to be. Consequently, we are creating ourselves according to what we think a person ought to be. This image is, then, what we think man ought to be. You are responsible for what you are and, as well, you are responsible for everyone since you choose for mankind. You create an image of man as it ought to be, since we are unable to choose the worse. In a sense, in deciding, I’m putting a universal value to my act by deciding in accordance with the belief that all persons in this situation should act in this manner. Our choices are a model for the way everyone should choose. If we deny this fact, we are in self-deception. If we say, “Everyone will not act as I have done,” then we are giving a universal value to the denial. We are responsible for ourselves–we are the sole authority of our lives. We cannot give up this responsibility except thought self-deception or bad faith. The anguish results from the direct responsibility toward others who are affected by our actions. Forlornness or abandonment is the consequences of the belief that we are our only source of value. We can’t count on God’s forgiveness or a pat on the shoulder. God is not the source of value; value can’t come from above. Sometimes this point is put following Dostoevsky and Nietzsche: “If God did not exist, everything would be permitted.” The inauthentic rejoinder, in Sartre’s view would be, “If God did not exist it would be necessary to invent Him.” We must take responsibility for our own choices. What can we find to depend upon? There are no means of justification or excuse for our actions. We do not have an external standard known to be right. None of the following are excuses:

“I did it because I’m a Christian”

“I did it because God commands it.”

“I did it because to err is human.”

“I did it because I am only human.”

We are condemned to be free because we are responsible for what we choose to be. The following are not excuses for how we act: from passion, “That’s the way I am,” “I couldn’t help myself,” “See what you made me do,” and “I just had to do it.” These all entail choices we have made. We are condemned to be free because we read the signs as we choose. We are condemned to establish our own values. As Margaret Anderson once wrote, “What an error it is to believe that suffering alone is enough for self-development. If it were, our planet would already be covered with saints and angels. Suffering kills some people; others are deformed by it; some become mad; only a few improve or progress. One must have more knowledge to benefit by suffering.” We act without hope because we cannot know in advance the consequences of our choices in the world. To choose not to choose is a choice, so we must choose. Despair results because there is no final authority but ourselves to help us choose rightly. We must choose without ever knowing the consequences of the choice. If I try to stop a robbery in progress, and the thief shoots someone, I’ll never know whether I did the right thing. I cannot predict the potential help or harm that result from my actions, yet I am fully responsible for the consequences of my actions.

Resilience and Faith

One of the most striking features in The Book of Job is the persisting preoccupation with the theme of suffering and regain of faith in the face of the horrifying reality. This is the result of the common legacy of both from the Hebraic tradition in which suffering has been a subject of serious concern from very early times.

The Judaic-Christian folk wisdom insists that even though God’s ways are beyond human comprehension, God acts decisively against suffering. Consequently, God is the human hope in the face of suffering. However reflective believers complain that God remains somehow responsible for the occurrences of suffering.

Nevertheless, the God who bears some responsibility for the occurrence of suffering is also the God who is believed by many to act decisively against suffering. This enhances the mystery about the causes and the meaning of suffering.

A. Koutsouvilis in his article “Is Suffering Necessary for the Good Man?” in The Heythrop Journal points out that some kind of suffering is essential for the good man. He sees guilt and innocence in terms of something higher than human thoughts, in terms of divine categories. He says that every human conception of fortune and misfortune and of what is joyful or sorrowful is erroneous. A man must recognize that with respect to God, he is always in the wrong. For example, Job was, humanly speaking, the most innocent of men, but he was constantly in the wrong in relation to God. Wisdom literature teaches that spiritual suffering is a necessity for the ethical and religious man. Koutsouvilis points out that inwardness, the core of the ethico-religious man, understands suffering as something essential. This inwardness is the relation of the individual to himself before God, it is the reflection into one’s own self Suffering derives from the fact that a man reflects into himself Absence of suffering signifies absence of religiosity, whereas in the presence of suffering, religiosity begins to breathe. It seems therefore that Socrates’ good mar must inevitably suffer as he realizes that while he is in the mortal state he is condemned to ignorance and is unable to comprehend what goodness really is. Koutsouvilis’ ethico-religious man also must undergo a kind of suffering as herealizes that being a man he is excluded from all that pertains to the divine.

In respect to God, man is always in the wrong. A kind of spiritual suffering then seems to be essential both for ethico-religious man and the kind of good man Socrates wished to become. This suffering is not merely the pains brought about by the words and actions of other men, but a realization of the inability to achieve the goodness or piety for which the good man strives. This suffering though painful, has beneficial effects in so far as it prevents the sufferer from forgetting his own inadequacies and ensures against a conceit of wisdom. James Aylward Mohler in his The Sacrament of Seering says that God humbles the soul in order to raise it. To be born again, the soul must be purged by a spiritual burning. The sod ascending to God must go deep within itself. The living flame of love touches and purifies the soul in a divine cautery. The soul delights being transformed into God. This sweet burn causes a delightful wound and the soul is purified.

The wound keeps enlarging until the soul is one great trauma and yet made whole again.

Suffering purifies, and purity deepens knowledge by which one comes to truth. Therefore, the soul that wants true wisdom must first begin to penetrate the depth of suffering. The Lord says to his people:

our wounds are incurable, your injuries cannot be healed and there is no one to take care of you, no remedy for your sores, no hope of healing for you. But, … I will make you well again I will heal your wounds, though your enemies say, Zion is an outcast; no one cares about her, I, the Lord, have spoken.

(Jer. 30:12, 13, 18)

His faith and trust in the angel as God-sent has saved him. He is reborn. Faith has triumphed over suffering. He learns through suffering. The sufferer turns into a believer. His quality like believing God and having faith in the God-sent angel leads him to higher perception. This quality has enlightened him to know that his plight is something more than a single individual can endure. Stanley Fish in his article Suffering, Evil, Existence of God observes the concept of suffering and quotes Milton’s Paradise Lost

John Milton’s Satan in Paradise lost says The mind is its own place, and in itself, can make heaven of Hell, and a hell of Heaven.

In Book 10 of Milton’s Paradise Lost, Adam asks the question so many of his descendants have asked: why should the lives of billions be blighted because of a sin he, not they, committed? (“Ah, why should all mankind / For one man’s fault… be condemned?”) He answers himself immediately: “But from me what can proceed, / But all corrupt, both Mind and Will depraved?” Adam’s Original Sin is like an inherited virus. Although those who are born with it are technically innocent of the crime — they did not eat of the forbidden tree — its effects rage in their blood and disorder their actions. God, of course, could have restored them to spiritual health, but instead, Paul tells us in Romans, he “gave them over” to their “reprobate minds” and to the urging of their depraved wills. Because they are naturally “filled with all unrighteousness,” unrighteous deeds are what they will perform: “fornication, wickedness, covetousness, maliciousness … envy, murder … deceit, malignity.” “There is none righteous,” Paul declares, “no, not one. “It follows, then (at least from these assumptions), that the presence of evil in the world cannot be traced back to God, who opened up the possibility of its emergence by granting his creatures free will but is not responsible for what they, in the person of their progenitor Adam, freely chose to do. Bart D. Ehrman, professor of religious studies and his book is titled “God’s Problem: How the Bible Fails to Answer Our Most Important Question — Why We Suffer.” A graduate of Princeton Theological Seminary, Ehrman trained to be a scholar of New Testament Studies and a minister. Born-again as a teenager, devoted to the scriptures (he memorized entire books of the New Testament), strenuously devout, he nevertheless lost his faith because, he reports, “I could no longer reconcile the claims of faith with the fact of life … I came to the point where I simply could not believe that there is a good and kindly disposed Ruler who is in charge.” “The problem of suffering,” he recalls, “became for me the problem of faith.” And as for the argument (derived from God’s speech out of the whirlwind in the Book of Job) that God exists on a level far beyond the comprehension of those who complain about his ways, “Doesn’t this view mean that God can maim, torment, and murder at will and not be held accountable? … . Does might make right?” The horror of the pain and suffering he instances leads Ehrman to be scornful of those who respond to it with cool abstract analyses: “What I find morally repugnant about such books is that they are so far removed from the actual pain and suffering that takes place in our world.”

Causes of suffering

Sigmund Freud, person behind the geneses of psychology, however far from the religion, dissects “suffering” psychoanalytically. According to him, Suffering comes from three quarters: from our own body, which is destined to decay and dissolution, and cannot even dispense with anxiety and pain as danger-signals; from the outer world, which can rage against us with the most powerful and pitiless forces of destruction; and finally, from our relations with other men. The unhappiness which has this last origin we find perhaps more painful than any other; we tend to regard it more or less as a gratuitous addition, although it cannot be any less an inevitable fate than the suffering that proceeds from other sources It is no wonder if, under the pressure of these possibilities of suffering, humanity is wont to reduce its demands for happiness, just as even the pleasure-principle itself changes into the more accommodating reality-principle under the influence of external environment; if a man thinks himself happy if he has merely escaped unhappiness or weathered trouble; if in general the task of avoiding pain forces that of obtaining pleasure into the background. Reflection shows that there are very different ways of attempting to perform this task; and all these ways have been recommended by the various schools of wisdom in the art of life and put into practice by men. Unbridled gratification of all desires forces itself into the foreground as the most alluring guiding principle in life, but it entails preferring enjoyment to caution and penalizes itself after short indulgence. The other methods, in which avoidance of pain is the main motive, are differentiated according to the source of the suffering against which they are mainly directed. Some of these measures are extreme and some moderate, some are one-sided and some deal with several aspects of the matter at once.

Voluntary loneliness, isolation from others, is the readiest safeguard against the unhappiness that may arise out of human relations. We know what this means: the happiness found along this path is that of peace. Against the dreaded outer world, one can defend oneself only by turning away in some other direction, if the difficulty is to be solved single-handed. There is indeed another and better way: that of combining with the rest of the human community and taking up the attack on nature, thus forcing it to obey human will, under the guidance of science. One is working, then, with all for the good of all. But the most interesting methods for averting pain are those which aim in influencing the organism itself. In the last analysis, all pain is but the complicated structure of our mental apparatus admits, however, of a whole series of other kinds of influence. The gratification of instincts is happiness, but when the outer world lets us starve, refuses us satisfaction of our needs, they become the cause of very great suffering. So, the hope is born that by influencing these impulses one may escape some measure of suffering. This type of defence against pain no longer relates to the sensory apparatus; it seeks to control the internal sources of our needs themselves. An extreme form of it consists in annihilation of the instincts, as taught by the wisdom of the East and practiced by the Yogi.

Intelligence: A double edged sword

Herodotus, father of history, says, The worst part a man can suffer is to have insight into much and power over nothing.

When it succeeds, it is true, it involves giving up all other activities as well (sacrificing the whole of life), and again, by another path, the only happiness it brings is that of peace. The same way is taken when the aim is less extreme and only control of the instincts is sought. When this is so, the higher mental systems which recognize the reality-principle have the upper hand. The aim of gratification is by no means abandoned in this case; a certain degree of protection against suffering is secured, in that lack of satisfaction causes less pain when the instincts are kept in check than when they are unbridled. On the other hand, this brings with it an undeniable reduction in the degree of enjoyment obtainable. The feeling of happiness produced by indulgence of a wild, untamed craving is incomparably more intense than is the satisfying of a curbed desire. The irresistibility of perverted impulses, perhaps the charm of forbidden things generally, may in this way be explained economically. Another method operates more energetically and thoroughly; it regards reality as the source of all suffering, as the one and only enemy, with whom life is intolerable and with whom, therefore, all relations must be broken off if one is to be happy in any way at all.

The hermit turns his back on this world; he will have nothing to do with it. But one can do more than that; one can try to re-create it. Try to build up another instead, from which the most unbearable features are eliminated and replaced by others corresponding to one’s own wishes. He who in his despair and defiance sets out on this path will not as a rule get very far; reality will be too strong for him. He becomes a madman and usually finds no one to help him in carrying through his delusion. It is said, however, that each one of us behaves in some respect like the paranoiac, substituting a wish-fulfilment for some aspect of the world which is unbearable to him, and carrying this delusion through into reality. When many people make this attempt together and try to obtain assurance of happiness and protection from suffering by a delusional transformation of reality, it acquires special significance. The religions of humanity, too, must be classified as mass-delusions of this kind. No one who shares a delusion recognizes it as such. We are never so defenceless against suffering as when we love, never so forlornly unhappy as when we have lost our love-object or its love. But this does not complete the story of that way of life which bases happiness on love; there is much more to be said about it.

In The Gay Science Nietzsche observes that: every art, every philosophy may be viewed as a remedy and an aid in the service of growing and struggling life; they always presuppose suffering and sufferers. But there are two kinds of sufferers: first, those who suffer from the over-fullness of life—they want a Dionysian art and likewise a tragic view of life, a tragic insight—and then those who suffer from the impoverishment of life and seek rest, stillness, calm seas, redemption from themselves through art and knowledge, or intoxication, convulsions, anaesthesia, and madness. Suffering is inevitable, and this seems to be evident in Nietzsche’s words (1974), p 328). It is in the attitude that we see the suffering, pain and trauma. All men of great success have gone through hell to achieve something. Whatever goes against our strongly guarded ideas is seen as suffering instead of realizing that nature is in flux and we are part of it. It is in this challenging world that we grow and mature not by living in some ivory tower or in a cocoon. This is precisely what even Foucault observes about the need for conflicts in order to evolve. Michel Foucault’s work the concepts of the individual self, of personal identity, of the atomistic subject, are considered to be little more than the residue of a rejected and decaying metaphysics. Yet when Foucault came to explore what he termed the care of the self, his attitude toward the individual seems somehow different. It is as if he is surreptitiously positing a new form of the individual, one markedly different than the traditional concept, with its basic suppositions of personal unity and continuity. It is this older notion of individual personhood that Foucault sought to supplant with his new ideas on the self and action. He sums up this conflict between differing notions of the self as follows: The theory of the subject (in the double sense of the word) is at the heart of humanism and this is why our culture has tenaciously rejected anything that could weaken its hold upon us. But it can be attacked in two ways: either by a “desubjectification” of the will to power (that is, through political struggle in the context of class warfare) or by the destruction of the subject as a pseudo-sovereign (that is, through an attack on “culture”: the suppression of taboos and the limitations and divisions imposed upon the sexes; the setting up of communes; the loosening of inhibitions with regard to drugs; the breaking of all the prohibitions that form and guide the development of a normal individual). I am referring to all those experiences which have been rejected by our civilization or which it accepts only within literature (Foucault, 1977, p 222).

- Beauvoir, Simone de, The Ethics of Ambiguity

- Book of Job

- Derrida, Jacques, The Death of a Friend: ‘The Work of Mourning’

- Fish, Stanley, Suffering, Evil and the Existence of God

- Foucault, Michel “Revolutionary Action: ‘Until Now,’” Language, Counter-Memory, Practice, trans. Donald F. Bouchard and Sherry Simon (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1977)

- Freud, Sigmund, Civilization and Its Discontents

- Kafka, Franz, On Suffering

- Milton, John, Paradise Lost

- Nietzsche, Friedrich, The Gay Science, Walter Kaufmann (New York: Random House, 1974)

- Sartre, “Existential Ethics” Introduction to Philosophical Inquiry

- Whitman, Sarah M., Pain and Suffering as Viewed by the Hindu Religion