By Greg Suffanti

Wijsheidsweb, quest book no. 2, June 2018

Chapter 1: “Always Do What You’re Afraid to Do”

Ralf Waldo Emerson

I wanted the gay version of the happy Hollywood ending

I had no way of knowing that when I said goodbye to Peter at the dawn of the new century, that he would be dead just over a year later. During the twelve years that we ultimately were together I was married to my idea of what my gay world should be.

I grew up watching shows like “The Brady Bunch” and “Bewitched”, and pictured myself tucked happily away in the suburbs with my stay-at-home partner and my fabulous career. I wanted the gay version of the happy Hollywood ending in a picture perfect world that was to be my promised future. “My American dream.”

Inwardly, I felt increasingly trapped, unhappy and ashamed of myself. Outwardly, I did my best to wear my mask of “Everything is Fine!”. I think I thought I could convince myself that I was totally okay just by willing “it” on myself. I was completely attached to an idea of what my life should be like, and this would only get me further away from myself.

The journey of moving to Amsterdam wasn’t just about the HIV/AIDS, it was really the journey of me going back to myself. However, at that time, I clung to what I thought life should be, and thus I doomed myself to failure and disappointment with my every turn and movement.

Our evil homosexual ways

It is said that the first stage of grief is denial. Between 1996 and 1999, my life became a semi-pleasant routine of working about fifty or more hours per week and then coming home and crashing in front of the television. I was ridiculously tired at the end of the day, but often enjoyed my work.

Peter didn’t work, and would do the cooking and shopping. We usually had a lot of fun together during the evenings, and I think we both very eagerly looked away from the HIV/AIDS, and sought distraction whenever and wherever possible.

Peter made his own pasta, and we ate fresh fruits and vegetables directly from his large garden that took up most of our backyard. We made light of the HIV, calling each other “diseased fags” and feigning southern accents, pretending to be self-righteous, born-again Christians, we’d condemn each other for our “evil homosexual ways”. Then we’d sentence each other to the “punishment for the faggots”, dooming the other to “gay cancer”.

It was turning the negative into something ridiculous, like playing with reality as a form of therapy. Peter had grown up in the South, and while there were some things he liked about his background, like southern manners, the open hostility towards “niggers and queers” that he had witnessed growing up, was not one of the things he missed.

Negative self-image

I think deep down these negative outer experiences contributed to my own increasingly negative self-image. Being gay back then meant having to fight against mainstream America’s conservative, anti-gay, “family values” viewpoint, just to see yourself as normal.

Having HIV/AIDS was the scary nightmare nobody wanted to talk about. AIDS consisted of nothing but misery and was shrouded in shame. HIV/AIDS was unspeakable. I grew up at a time when gay men were mocked and ridiculed in both film and television. Some things in America have really changed for the better.

For Peter and I, levity and irreverence kept the realities of the world at bay. Safely distant. There were two separate worlds back then: your private gay world and the straight world. Peter often joked that his two T-cells (the fighter cells that keep a body healthy) really had to work overtime to keep him healthy.

Peter nicknamed them “Tom and Jerry”. We made jokes about the OxyContin, which made our pupils smaller, teasing in the same feigned southern accents, accusing, “look at them pupils! You be stoned, boy!”

There was life after AIDS.

We laughed a lot

Peter was lucky that he only had three KS lesions on his right leg. Kaposi sarcoma is related to the herpes virus, and when active, causes cancerous lesions to grow. KS is considered an AIDS-defining illness. His secret was safe from view. Peter looked “normal” then, and healthy, with his blond, curly hair, clear green eyes, and his tanned, toned body.

After all these years, we’d become platonic friends. Our sex life effectively ended with the HIV/AIDS diagnosis. I was too busy with work then to even think about sex. Now I felt too diseased to even consider myself desirable or even attractive. There was a heaviness to the whole HIV/AIDS situation, but there was also a sort of festive, devil-may-care attitude about life in general, knowing it could end at any time.

In pushing the HIV/AIDS to the background, it became easier to deny that this unwelcome visitor was capable of wreaking any real havoc in our lives. Peter and I were now really just friends, but we were good friends and we laughed a lot.

It became very easy to have that drink in the evening, buy that new car or go on that vacation. Peter bought a motorcycle and made some new friends in the gay scene via our new computer, and I was promoted from sales manager, to co-director, to director of my firm within the span of three years. I was gregarious and genuinely liked people, and in a way I became outwardly like a Hollywood actor, making jokes and working hard, trying to portray the perfect husband and business leader in the role that was my own life story.

No clue about being genuinely happy

Keeping busy meant not thinking about the HIV/AIDS. When I wasn’t working, I was usually talking or thinking about work. I don’t think I had any clue about being genuinely happy, because I was too caught up with trying to be perfect. I was doing what I thought I should do, and was unwilling or too afraid to really challenge myself about what actually might work for me.

I didn’t look at Peter as young and having needs, I looked at Peter only as having AIDS. The HIV/AIDS felt like a wall separating me from any sort of future; it was my dream-killer. Peter and I had met when we were quite young and we grew further apart as people as the years passed. I never entertained the idea of another man from the moment I found out about his having AIDS. I resigned myself to my fate and tried to stay focused and work even harder.

For those brief few years, work seemed to offer some sort of consolation; until I started to ask myself what I thought I really needed and wanted in order to come closer to the ever elusive feeling of happiness. Until I met Amsterdam. The OxyContin would also play a role in my ultimately choosing the path of hope and optimism. First though, the “non-addictive” OxyContin would give me my first taste of battle with addiction. Narcotic style.

Made possible by the benevolence of the Dutch social system

Peter and I were a young couple in liberal Seattle, and like most young couples living in Seattle with adequate means, we enjoyed weekends in Canada or in the mountains or deserts of Washington state. We had vacations to Nevada, Hawaii, Mexico and the East coast.

Put aside the illness and the side effects of the medicines, and you had two young men who wanted to do things and go places. The reality of HIV/AIDS changed everything, but as the Dutch say, “alles went”, you can get used to anything. After the shock, life moved forward, and we went with the flow.

Although I felt crushed at the time, Peter’s falling in love with someone else was natural, given my workaholic nature. I refused to accept my death sentence, and took to proving the world wrong through work and material success, while Peter always felt he was going to die, and looked for the comfort of another human being. Not surprising in hindsight.

These were heavy lessons for me to learn at a young age, and I’m thankful to have had the time since then to work at resolving the disappointments that my life seemed to represent. I’m also eternally thankful to have had the space and the help to be able to see myself as whole and healthy again.

This was and is an ongoing healing process, spanning more than twenty years, and made possible by the benevolence of the Dutch social system and the different people who’ve helped, guided and inspired me through the years.

An Opium-Den-of-Hope

Back in the Seattle days, both Peter and I were treated by Dr. Dean Smith. The offices of Drs. Dean and Dan Smith, fraternal twins, gay, Internists, specializing in HIV/AIDS care and then located in a chic new building in downtown Seattle, became for a time, a sort of opium-den-of-hope for hundreds of mostly young gay men who were the victims of a brutal epidemic, also referred to then as “GRID”, or gay related immune deficiency.

In the late 90’s, they were the narcotic Florence Nightingales for that scariest and most unwanted of scourges, called AIDS. Here, being gay and having HIV/AIDS was normal. Drs. Dean and Dan didn’t wear gloves when they touched you, and because they specialized in HIV/AIDS, all the patients you saw there were just like you. Beside my home, this was the only place I could talk openly about my secret world.

The waiting room of their practice was less an office and more a living room, with tasteful oil paintings of landscapes, couches, and end-tables with lamps. Actually, it looked like something out a soap opera, complete with plastic plants and dim lighting. The atmosphere was so homey, it felt as if nothing bad was ever going to happen there.

A toxic mix of medicines

Dean and Dan were tall, thin, in their mid-forties and respectable looking. Almost professorial. They both wore white lab coats with pressed shirts, dress pants and silk ties. Dan wore athletic foot gear, Dean wore shiny dress shoes. Dan had a moustache, and Dean spoke with a decidedly gay lisp, which had the effect on me of making everything he said sound less serious. I found his way of speaking to be both sincere and endearing.

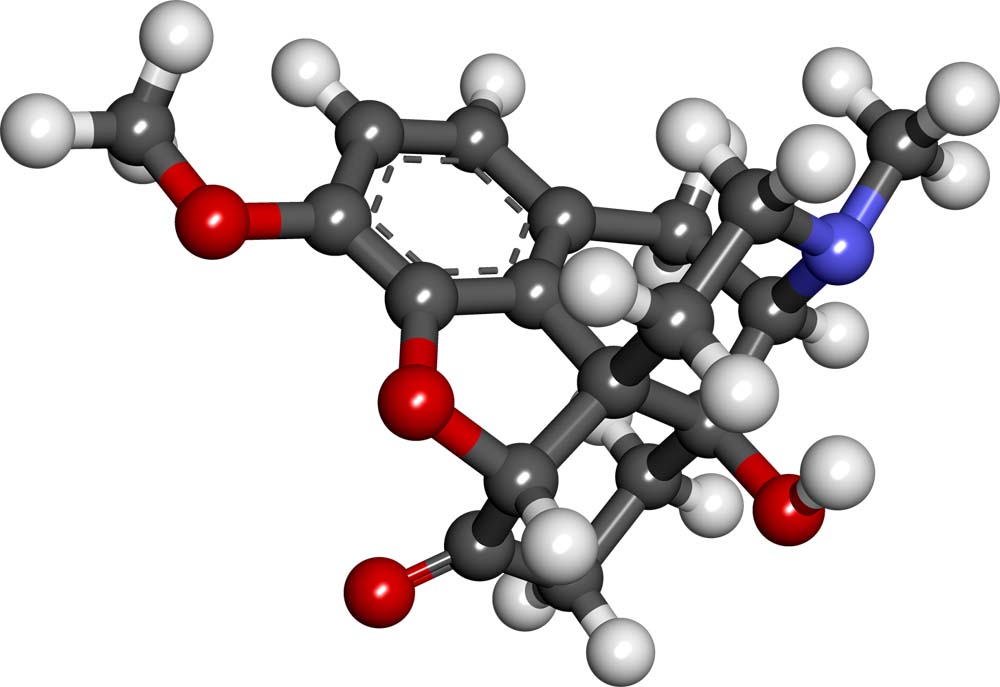

They were well-versed in the latest developments in the world of HIV/AIDS, and they prescribed copious amounts of the new “non-addictive” painkiller OxyContin to combat the ravages of HIV/AIDS. Both Dr. Dean and I were happy that this new drug seemed to give me freedom from the effects of the HIV, and of course, the HIV drugs themselves.

Back then I took a toxic mix of medicines, including the drug AZT. AZT was used in combination with other antiretroviral drugs and was taken every four hours, day and night. That method of treatment was called HAART: Highly Active Anti Retroviral Therapy. Rather than getting gaunt and frail, I was getting chunky and sedentary. I enjoyed discussing my work with Dr. Dean, and he always had a personable way about him that made him seem more like a friend than a doctor.

Everyone called them either Dr. Dean or Dr. Dan. They were serious enough in their diagnostics and treatment protocols, but were also gay enough to make a visit fun and homey feeling. “Do you need more pain meds sweetie?” Dr. Dean would ask me at the end of an appointment. There was a real buzz to the place, and I actually looked forward to my appointments. It was like visiting your favorite “gay uncle”. I always felt better after seeing Dr. Dean.

There was nothing normal in the world of AIDS, except death

The two doctors had a waiting list of over a year, as gay men with new diagnoses of HIV/AIDS flocked to their ever-growing practice.

At the time, thousands of mostly young men were dying of terrifying and scary illnesses, going blind, going crazy and getting old and dying, almost overnight. This is an epidemic that has not gone away.

The CDC (Center for Disease Control) in America estimates that in 2016, 36.7 million people worldwide were infected with the HIV virus. Of this group, approximately 19.5 million people were receiving treatment.

In 2016 the death toll from AIDS-related illnesses was 1 million people. Left untreated, the HIV virus replicates until it cripples with illness and then it kills its host. Some of the illnesses that advanced HIV causes are: cervical cancer, cryptosporidiosis, histoplasmosis, lymphoma, toxoplasmosis, encephalitis, wasting syndrome and many more.

Admittedly the twin doctors both seemed a bit strange at times with their ever flirtatious air, but, in the AIDS-filled world at that time, their strangeness wasn’t so strange; just like it wasn’t so strange to see dying young men waiting for their appointments in the cozy waiting room of Drs. Dean and Dan.

There was nothing normal in the world of AIDS, except death. I think they both did the best they could under difficult circumstances, a period in which there were mostly sad endings. They offered what expertise was available at that time, an in-house blood lab, and plenty of support and kind words, always encouraging a hopeful outlook.

That hope captured and harnessed my whole being

Towards the end of the last century, I discovered that the “non-addictive” OxyContin, was in fact very addictive. It would be physically and emotionally draining to end my use of the drug, but after falling in love with Amsterdam, my dream of a new life won out over my need to dull my pain and my painful reality. I wanted to live. Fully.

It was often painful to look at other young people enjoying themselves when I felt so imprisoned by both my illness and my new addiction. Life felt too heavy with problems, and I didn’t seem to have any sort of perspective or answers to solve any of my difficulties.

The pain and the pain medication made me feel hollow inside and increased my feelings of helplessness. When I felt I had no positive future, all of the pains and problems I had seemed bigger. Hopeless. Without the OxyContin it took years to get used to the fact that my body was full of aches and pains all of the time.

Similarly, the HIV virus and the drug “cocktails” used to treat the virus, left me permanently tired and feeling sickly. I was constantly dizzy, nauseous and fatigued, and I started developing polyneuropathy, which gave me pain in both legs, and increasingly less feeling and numbness in my hands and feet.

A future of inclusion

This situation caused me much stress, and although my love for Amsterdam would carry me for a good few years, I spent the first ten years of my journey with HIV/AIDS expecting to die at any moment. My physical reality anchored my mind in my own demise, while another part of me fought for a chance at a new life.

In the Netherlands I was being offered the hope of a future of inclusion. In America, my future was bleak. I remember the feeling of hope I felt when I first dreamed of moving to Amsterdam and envisaged what my life might be like. That hope captured and harnessed my whole being, it filled me and it gave me the courage and the will to go on, because there was something positive to go on to. I saw no future in America, except slipping further into the world of AIDS, illness, poverty and exclusion.

The opioid crisis now plaguing America

I look at the opioid crisis now plaguing America, and I understand the pain that a hopeless future outlook brings: it is the child of desperation seeking the comfort of a nurturing Mother. Without hope, there are no dreams, and without dreams there is no future.

OxyContin would become the famous gateway drug to the current opioid crisis in America. In 2016, it was estimated that 59,000 Americans died because of drug related causes. This is even higher than the estimated 45,000 people that died in 1995, at the height of the AIDS crisis. Drug overdose is now the leading cause of death in American for men between the ages of 18-50.

I will always love America, and I will always respect America, but I will never understand how healthcare in America is viewed as a privilege and not a right. If America can ask her citizens to die in foreign wars on her behalf, why can’t she offer healthcare to those at home in times of illness and tragedy? How many lives have to be destroyed before the governing forces in America truly prioritize their own citizens?

The ‘Polder Model’ ensure that minorities are protected from the possible tyranny of the majority

I became a Dutch citizen in 2008. The issues of healthcare and a social system of safety nets are two of the main reasons for this decision.

The Netherlands’ famous “tolerance” also played a significant, if not defining role, in my taking the necessary steps to become a Dutch citizen. In the Netherlands, the Dutch are permanently engaged in what is called “polderen”. The Netherland are a social and economic consensus society. This way of living and governing means that everyone has a voice, and that decisions are made only when a consensus has been reached.

Dutch politicians are beautifully boring in their unwavering commitment to each person’s basic rights and individual liberties. The “Polder Model” as it is commonly called, ensures that minorities are protected from the possible tyranny of the majority.

This has far reaching repercussions, not only legally, but also socially, where respect and tolerance play out in mostly harmonious neighborhoods, and where cities and towns are places where women walk safely outside at night.

The strongest shoulders should carry the heaviest load

Looking at everyone as having equal value and sharing resources is referred to in Holland as a philosophy of “wie de sterkste schouders heeft, zou de zwaarste lasten dienen te dragen”. Meaning, whoever has the strongest shoulders should carry the heaviest load. When you add to this a high standard of living, it becomes obvious why the Netherlands are consistently ranked as one of the happiest countries on earth.

My mom raised me to see myself as a human being, an equal human being, and not to see myself as a label, for example, “a gay man”. The laws of this country reflect my values and protect me in my work life, my home life, and my personal life. This is true democracy, on paper, in black and white.

As the Dutch would say, “het spreekt voor zich”, it speaks for itself.

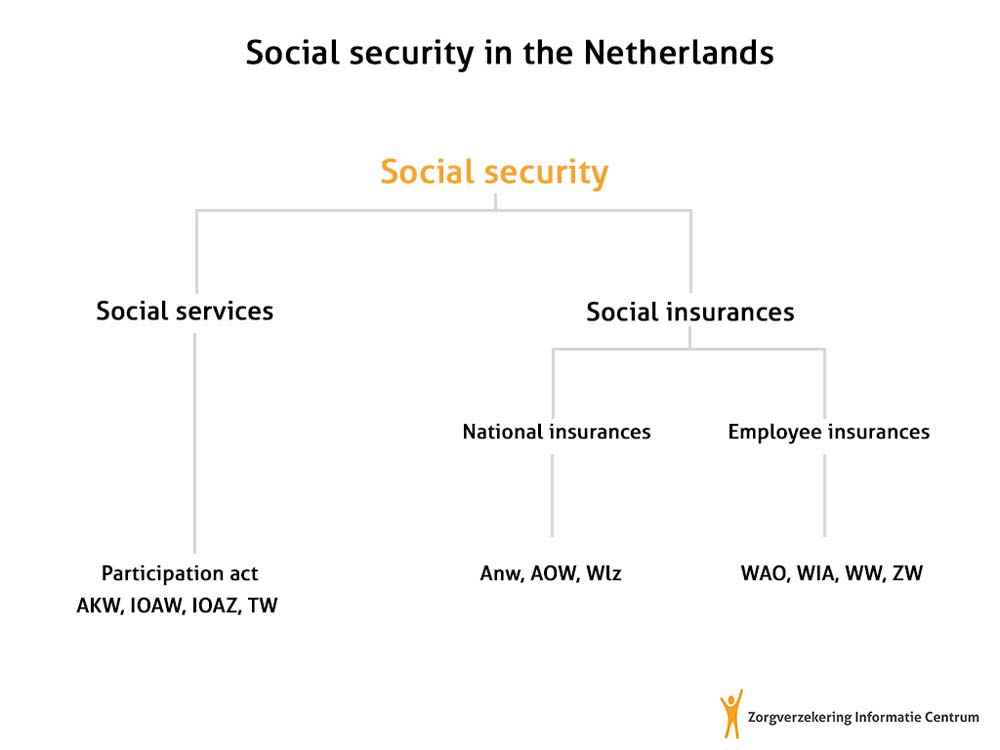

In the Netherlands, there is an attempt to create a social system that provides a basic existence to each citizen and under all circumstances. If you are sick, you are treated, with no additional costs. This includes doctor and specialist visits, all medicines, most surgical procedures and rehabilitation and aftercare.

There are individual insurance companies in the Netherlands, however, the whole system operates collectively, which means costs are kept under control. This includes the costs of prescription drugs, whose limits are determined by the Dutch Minister of Health, Welfare and Sport, and the Dutch government.

If you lose your job, you collect 75% of your income for two years, so that your life doesn’t fall apart because you no longer have a decent income. If you are sick or can’t find work, you’ll be given an income, so that you can live as a dignified human being.

If you need a home, you can find one through the system of social houses, and if you can’t afford the rent, you’ll be given a “huursubsidie” or rent subsidy.

High happiness quotient

There is even “vakantiegeld”, or vacation money, given to everyone at the end of May, including people on welfare, because the state believes that everyone should be able to have the possibility to rest and relax and get away.

Universities cost a couple of thousand Euros per year, not a few tens of thousands of dollars.

As countries move away from already inadequate social spending, they should look at the high standard of living in the Netherlands, its happiness quotient, and its low crime rates, and see the wisdom of investing in a common future for all.

Survival of the fittest is simply not fair, and both America’s drug epidemic as well as her violent crime rates, attest to the results of systems which deny and exclude citizens of support and essential help.

Capitalism and socialism can work in tandem

There seems to be an understanding amongst Europeans in general that all citizens have value and basic rights, and that it is the role of the respective governments to facilitate the exercising of those basic rights.

Unfortunately, there are warning signs in eastern Europe that right-wing conservatives are gaining ground in sowing the seeds of hatred and intolerance towards immigrants, and in some cases, against the LGBT community.

Growing up in America, I never questioned her basic premise that socialism was inferior to capitalism. In my mind, it was an either or proposition. After nearly two decades in Europe, I see that these two entities don’t have to be diametrically opposed to each other. In fact, capitalism and socialism can work in tandem, as they’ve been proving now for more than seventy years in a peaceful and united Europe.

It is a shame that America seems to have lost sight of a more social vision, a vision she herself urged Europe to adopt in her Marshall Plan after the second world war. Europe is alive and well, thanks to America’s Marshall Plan, and living proof that societies that share more, benefit more. Europe’s high standard of living, good access to education and low crime rates are proof that inclusiveness means prosperity at all levels and in all ways.

Back in the summer of 1998 I needed to think about my life

Back in the summer of 1998 I was years away from all the changes that would come with my new life in Amsterdam. During that summer I began reading books on Tibetan Buddhism. I was spiritually thirsty, and I drank the wisdom of what I read as though I’d never drunk before.

I intuitively knew that the Buddhist way of life was for me. Everything I read felt like personal advice. I also began to see how incredibly far away I was from myself and how all of my energy and attention had been going out.

Suddenly, the sanity of Buddhism was calling me to look inward to find the solutions to all of my problems and suffering. Somewhere I’d read a quote from the Buddha that said, “pain has made you ready to learn”.

Yes, I felt ready to learn. I was desperate for answers in my life. I was desperate for something else other than a life which seemed to be falling apart. A life without a future.

I was HOME

Peter and I had grown apart, and his new relationship hung over our heads; we were like a couple still living together in spite of being divorced. I didn’t know how to end our relationship, and Peter’s AIDS diagnosis made me afraid for his future. Afraid to let him go. I told him this. In Peter’s mind, there was no problem, and he genuinely wished me the happiness he now felt he had.

I needed this trip we were planning. I needed to get away. I needed to think about my life. My uncertain life. My life alone with HIV/AIDS. Buddhism was shining a mirror of reality at me, and the person I saw in the reflection was a total stranger.

In September of 1998 Peter and I visited western Europe. After spending five days in London, we flew to Schiphol airport in Holland, where we planned to spend the night in Amsterdam, get our rental car the next morning at the agency, drive to Paris, and then spend nearly four weeks leisurely exploring the rest of France and Spain. Those were the plans.

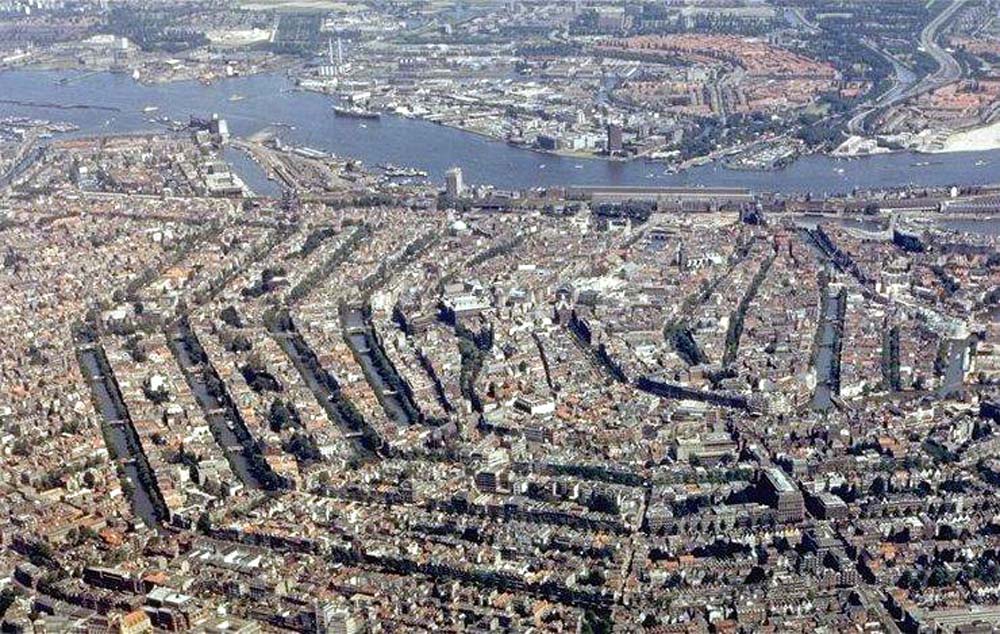

I had never been to the Netherlands before, let alone Amsterdam, so I was completely taken aback by my reaction to the city of bikes and canals. I was absolutely floored by its beauty, its architecture, its picturesque canals and its open way of life.

Everyone seemed open and free and happy.

Amsterdam was the first place I’d ever been where I felt like I was home. And normal. From the moment I placed my feet on her brick-lined streets and sidewalks, I craved this walkable, charming place of gabled houses and bridges that arch over tree-lined canals. Peter was less enthralled than I was, but, he also liked the city very much, and we mutually agreed to extend our visit from one night to five nights.

Dutch tolerance was not only welcoming, it felt like an enlightened way of living

There was a relaxed vibe in Amsterdam and I felt free as a gay man for the first time in my life. I would see Paris and Biarritz and Madrid and Seville on that trip, but my thoughts and my heart kept pulling me back towards Amsterdam. I felt magically and magnetically attracted to this beautiful and old city that had been welcoming the unwelcome of the world since 1492, when Jews fled to Amsterdam to escape persecution from Catholic rulers in Spain.

Homosexuality was decriminalized in 1911. It would take the U.S. Supreme court until 2015 to achieve similar laws nationwide in America. For the first time in my life it didn’t feel strange to be gay. I didn’t feel “different”. In Amsterdam, the harmonious way that everyone got along opened my eyes to a new way of living. Dutch tolerance was not only welcoming, it felt like an enlightened way of living.

Amsterdam’s “live life any way you want to” energy was infectious, and I enjoyed hours of sitting in “coffeeshops” and cafes, tasting another way of life that filled and intoxicated me in every sense of the word. What was normal in Amsterdam was thrilling and new to me.

I was so focused on going to France and Spain, it had never occurred to me that I might even like Amsterdam. I began fantasizing about living there almost immediately after arriving. We spent our last week in Amsterdam as well, and by the end of that month in Europe I would know with certainty that I had met the great love of my life: Amsterdam. I was hopelessly hooked.

I was going to do what I was most afraid of doing

Somehow, some way, I was going to move to Amsterdam. I was now open to my own new and exciting future. My life made sense to me when I imagined working and living in Amsterdam and studying Tibetan Buddhism.

I was going to make it in Amsterdam or I was going to die trying. Just a few months earlier I’d had no positive outlook on my life, and suddenly I’m consumed with passion to follow my new dreams.

I decided I wasn’t going to focus on being sick. I was going to focus and believe in my positive future. They say that when one door closes, another opens. The HIV had changed my life forever, but so did visiting Amsterdam, and so too did seeing His Holiness the Dalai Lama one afternoon on CNN’s former program, “Larry King Live”.

I was alive again

I was so struck and moved by the genuine joy and happiness of His Holiness, that I went out and bought some books on Tibetan Buddhism. I was immediately taken with what I read and have not looked back since. Twenty years ago I began dreaming about a life in Amsterdam, and twenty years ago I began to dream of following the Buddhist path, dreaming that I might one day find happiness… as a Buddhist, in Amsterdam.

During the following months, I’d end my career and my partnership of a dozen years. I was being pulled forward, almost magnetically, toward an entirely new and different way of life. I would have no idea how my future was to play out, all I had then was a wish and a dream to belong somewhere: to feel welcome and at home.

I was terrified a great deal of the time, on the other hand, it was incredibly exciting to think of me, the American, starting a new life in Europe. The idea of becoming European was exotic to me. The idea of living in Amsterdam filled me with a sense of wonder and a feeling of going home.

I was going to do what the great American writer Ralf Waldo Emerson advised, I was going to do what I was most afraid of doing. For the first time in years, I was alive again. The future was bright.

The future was Amsterdam.

End of Chapter One.

Chapter Two: “God Made the World but the Dutch Made Holland”

(To be continued…)

Notes

[1] Source: happy ending

[2] Source: awarness aids

[3] Source: Amsterdam births eye view

[4] Source: Florence Nightingale

[5] Source: Oxycodone

[6] Source: polder model explanation

[7] Source: social security in The Netherlands

[8] Source: Buddha footprint

[9] Source: Amsterdam-Canal

[10] Source: Larry King and His Holiness the Dalai Lama