Louise Müller

Wijsheidsweb, January 24, 2020

The aim of this ‘deep water’ blog is to share my ideas about the design of the Musee du Quai Branly (MQB) and its collection of non-western cultural and artistic objects. The MQB, is designed by the French architect Jean Nouvel, who aimed to adapt the museum building to its environment. The building is surrounded by a garden created by the landscape architect Gilles Clement, which functions as a backdrop of the museum’s World Collection. The MQB is dedicated to the arts and cultures of Asia, Oceania, Africa and the Americas.

For Nouvel, the MQB building, which also gives home to a hanging garden (designed by Patrick Blanc) and a ceiling with Aboriginal art, are like the lines of a poem. The World Collection, which makes up the content of the museum, is akin to poetic ideas and sentences.

Water connecting world arts and cultures

I found the MQB building, its surrounding garden, and the display of the objects aesthetically highly appealing. I have visited a large number of ethnographic museums and museums of non-Western art worldwide, and to my mind most of them are not as visual attractive as the MQB collection. One enters the building via a ramp, which gives space to the changing art projects of video artists. I entered the museum by walking in a river of moving words comprising of all the people and geographical locations displayed in the museum’s collections projected with varying rhythms and concentrations, which brought me to the entrance of the Permanent World Collections.

According to the Scottish video artist Charles Sandison, the creator of the ramp’s installation, ‘the wealth of the cultures flows like the words through time and space, like water’. Sandison ‘encourages the visitor to imagine relationships between the signs and to dream about it’. Certainly, the MQB’s World Collection is set up as a dreamlike experience. Each continent has its own colour, and the space is not only filled with exhibits but also with video screens and ‘sound worlds’. By entering the collection, I am greeted by a wooden figure, an androgynous fertility symbol, which originates from the Dogon people of Mali. The figure, which has both a beard and breasts, waves at me thereby recreating the gesture of creation itself. The figure was preserved in the cliff of Bandiagara, which served as a cemetery. The dry microclimate of the cliff prevented the statue from rotting and so does the dark but carefully acclimatized MQB building.

Accompanied by some frugal rays of light, I continue my journey to this dream world by walking through the African collection, which is marked yellow on the pallet of colours that makes up the map of the museum. The African collection of the MQB consists of over 89,000 objects, which makes it one of the largest collections of African art in the world. The core collection of the Africa section of the museum is made up of pieces, especially masks, of Mali, Côte d’Ivoire, Nigeria, Gabon and Congo.

African masks and Cubism

An object that struck me in the African collection is a blue-white feathered wooden mask, which belongs to the Krou people, which assimilated with the Grebo, who live in the southwest of the Cote d’Ivoire. Like many Africans, the Krou people used and still use African masks in religious ceremonies to bring to life the spirits of the ancestors. The bearer of the mask transforms into a medium between the spiritual and the social world and (s)he translates the messages of the ancestors to the living.

The protruding eyes and mouth of the figure and the feathers on its head give prestige to the mask bearer, who acts as a spirit medium. In 1912, this mask of the Krou people (see above) and other African masks became the source of inspiration of French modernist artists, and especially Pablo Picasso and George Braque.

In June 1907, Picasso visited the Palais du Trocadero, whose objects have currently become part of the MQB collection. Besides the Krou mask, Picasso was also inspired by a mask of the Dan people, which are hunters and farmers whose territory stretches from the western side of the Côte d’Ivoire into Liberia. Dan masks are also used by spirit mediums in rituals. They are sacred objects that are used for personal protection of those Dan people who live away from home. A Dan mask (right) inspired Picasso to paint ‘Head of a Woman’ (left) that same year.

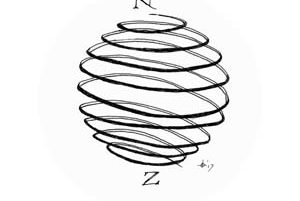

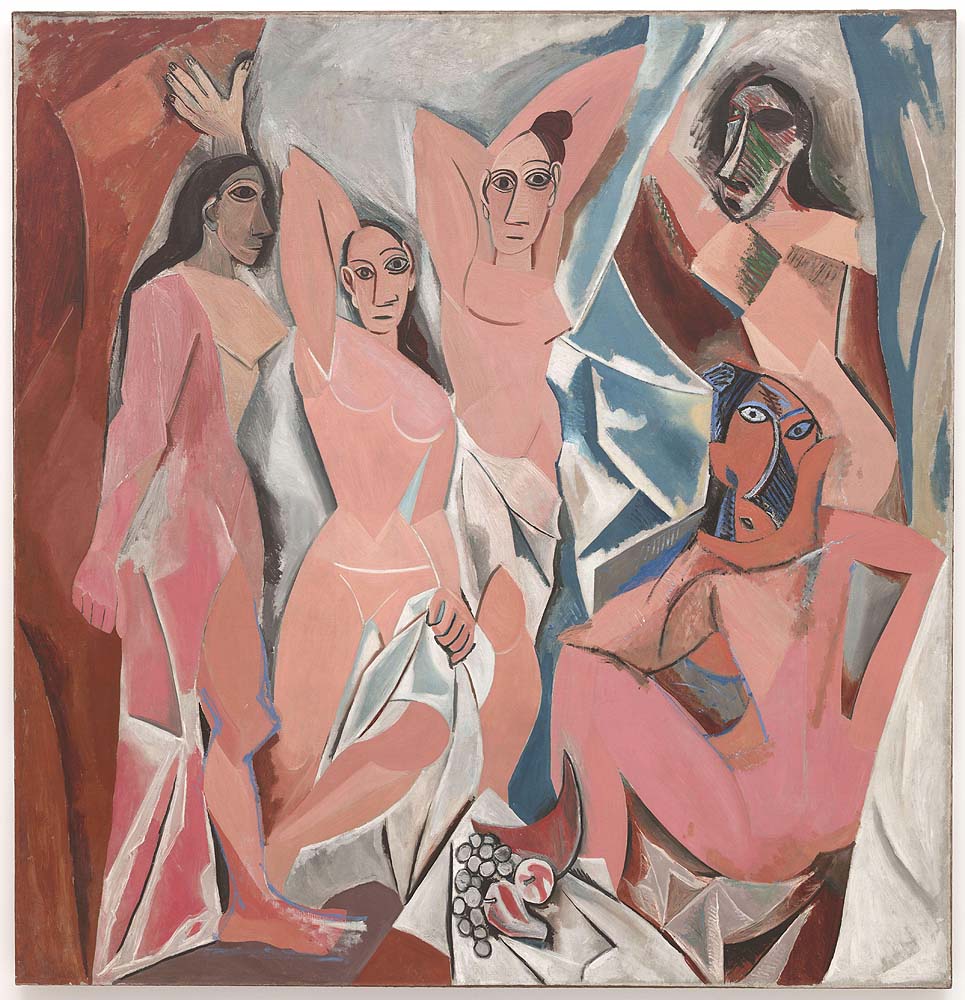

A Fang mask, of the Fang people of Gabon, was the source of his artwork ‘Les Demoiselles d’Avignon’ (1907, see under), which is often marked as an expression of proto-Cubism. The artistic movement of Cubism that grew out of these early works of modernist painters, aimed to create artworks that were closer to the real human perception objects, which is not three dimensional and one-directed. In line with the modern findings of the non-Euclidian geometry, the Cubistic painters designed a visual world that was two-dimensional and multi-directional, which enabled them to display objects from different perspectives at the same time just like the human eye. The non-Euclidian geometry is in many aspects similar to the indigenous worldview of many Africans. It is therefore not surprisingly that these modern painters found the solution for the visual impairments that Renaissance art schools had brought in this so-called ‘primitive’ African artwork.

Whereas these Renaissance Beaux Arts schools held that non-Western people had no art or inferior art, the Cubists praised non-Western artists for being more poetic and closer to nature. Their appreciation of the artwork of the indigenous people of Africa, Asia, Oceania and the Americas was born out of a critique on the North Atlantic modern societies and the presumed loss of modern men of its pure natural soul. One of the critiques on MQB is that with its praise of the Cubistic painters, the museum also reinvigorates the dark side of primitivism as an artistic flow that reflected a male, patriarchal and colonial perspective of non-Western arts and cultures, which was interwoven with racial and sexual fantasies. Especially women of Africa on Cubistic paintings were often portrayed as eternal available creatures with an inexhaustible desire for sex with white male colonizers.

Water and postmodern interculturality

The MQB presents itself as a museum, which promotes the dialogue between world cultures on an equal footing, but can it do this without developing a written postmodern critique on the colonial history of its collection? Maybe the answer is yes. Perhaps the most promising attempt to such an intercultural dialogue is not in the written word that accompanies the artworks of predominantly the Global South but in the symbolism of the water that binds them.

By following the river of words, the visitors of MQB float to the seas and oceans that connects the continents of the Global South. Water is always in search for new associations thereby symbolising the bond between global cultures. Both our environment and our own bodies consist of two-third of water and one-third of matter. Our globe and we human beings are thus for the greater part made up of this fluid of connectivity.

Water is a colour, gender and race neutral substance and it flows through all of us as mysterious as it flows through landscapes and across continents. Water connects our inner microcosms with the outer macrocosms and it enables us to unite with the consciousness of the wider world. Water is ryzomatic; it is non-linear and non-hierarchical. It permeates both our environment and us and by glaring at it, water helps us to feel being emerged in the totality of reality.

Instead of historical ideas that are often lineal and central, water is decentralized and multiple dimensional. Water is like music, a horizontal plane of endless tonal relations, it is like the Internet; a web of communication. Water is eminently a substance with a structure that corresponds with that of the postmodern society.

The intercultural connectivity of global cultures is thus indeed articulated in the Musee du Quai Branly albeit its form of expression is rather poetic and a-historical.

Notes

[1] Source: blue-white feathered wooden mask

[2] Source: Les Demoiselles d’Avignon.

[3] Source: This 19th-century Fang mask is similar in style to what Picasso encountered in Paris just prior to Les Demoiselles d’Avignon.