The Role of Mindful Emotional Intelligence in Self-Regulation and Resiliency

Carlo Monsanto and Andreea Petruse

Wijsheidsweb, January 2018, the complete paper – (pdf)

Our whole cubic capacity is sensibly alive; and each morsel of it contributes its pulsations of feeling, dim or sharp, pleasant, painful, or dubious, to that sense of personality that every one of us unfailingly carries with him.

William James

Introduction

In 1972, the Chilean biologists Humberto Maturana and Francisco Varela defined the self-maintaining chemistry of living cells as Autopoiesis. This is the capacity of living systems to reproduce and find balance (1). In the past century our global society has evolved to a point where we’re able to make technology that can reach other planets or zoom into the minutest parts of the body and manipulate genes. Despite this vast knowledge and understanding accumulated in millions of libraries around the globe, we have yet to figure out the laws that govern our subjective world within. Modern science is only now opening to the possible answers explored by ancient sciences and wisdom traditions for thousands of years. Even within the gradual, worldwide adoption of the Mindfulness practice, we lack the full understanding of explaining how this, and other contemplative practices, affect us internally. In this foundational article, the authors present a heart-centered and first-person approach to studying subjective experience. The objective is to enhance Mindful Emotional Intelligence as an instrument that can be used to learn the necessary details of our subjective world, while optimizing how well we process and integrate our present reality. This supports both psychological and physical healing as well as personal and social expression. Within an educational environment, this inner learning process activates the feeling-right-brain, balancing deductive and inductive ways of processing information, thus improving learning outcomes for both traditional and alternative curricula.

At the Mindful Connection Institute, Princeton, Carlo Monsanto and Andreea Petruse study how this mechanism for self-maintenance depends on how well our nervous, metabolic, and immune systems work together as a whole. The integrity of these systems may be considerably disrupted by “stress responses”. Stress is generally caused by three internal biological responses associated with fear, sadness and rejection; each response relates to how the body is internally programmed to react electro-physiologically through the aforementioned body systems.

Learning objectives

We offer this paper as a reference work to leverage our goal of designing and implementing Applied Social Emotional Learning (A-SEL) processes in education, supported by specifically designed SEL stratagems and programs in schools, colleges, and PTA’s. SEL programs can be designed to rebalance existing curricula and after-school programs to make learning more effective, reducing incidences of stress related disorders, such as anxiety, obesity, ADHD, bullying, depression or suicidal tendencies. Socially, stress is often perceived as “good for business”, but from a health perspective stress is more readily recognized as a culprit of disorder and disease. Through Applied Self-Assessment Psychology (ASAP), students may be guided to enhance Mindful Emotional Intelligence (MEI) and engage in first-person-research, internally navigating and tracking their own internal progress to release stress.

How does this translate into a genuine sense of contentment and a love of learning? There are different ways of attracting happiness in life – lifestyle and diet changes, positive thinking, contemplation or mindfulness, all are helpful in cultivating a more positive attitude towards life and learning. Through Applied Self-Assessment Psychology (ASAP), a person experiences contentment as an inner mental–emotional state, which can be cultivated through the awakening of one’s inborn capacity to be aware and discerning. This process profoundly affects and transforms how one sees self, others, and the world as a whole. The learning objective is to be effortlessly aware and discerning all the time, even during activity, thus increasing our capacity to experience and direct our lives in a more connected and confident manner.

Applied Self-Assessment Psychology (ASAP) not only helps one understand how biological response patterns influence our psychological and physiological systems, but also how they may be effectively resolved through developing MEI. This work guides the reader towards studying the nature of conditioned responses, how they manifest and from where they originate. Following these guideposts facilitates an internal path towards resolution, balance and healing.

Applied Self-Assessment Psychology

For the most part, this process of enhancing MEI is self-guided through ASAP which in turn is largely inspired by Ayurvedic psychology (4). Ayurvedic psychology is a modern branch of the age-old traditional system called Ayurveda. ASAP is similar in a way to Mindfulness practice, which is derived from a Buddhist contemplative practice called Vipassana. What both practices have in common is their focus on restoring the individual’s present moment awareness. In addition, ASAP envisions the use of an internal frame of reference and a system of internal feedback to enhance MEI (4) – this supports the activation of a person’s own ability to sustain a state from where experiences are effortlessly recognized as they unfold in the mind and body. This inductive way of “learning-by-doing” is at first guided externally through a mentor. The mentor helps bring awareness and attention to what is triggered internally in-between the stimulus and the response, emerging from beneath the conscious level. Mindful Emotional Intelligence (MEI) grows as the learner witnesses how negative traits appear, are integrated and disappear, leading to greater levels of personality integration. Self-assessment further enhances one’s ability to dynamically recognize specific patterns, through the unlocking of underlying emotions, sensations, and memories to facilitate inner growth. MEI is an innate capacity that holds the key to metabolizing negative emotions and restoring balance on all levels. The student develops a level of sensitivity and awareness that constantly evokes self-regulation, healing responses, desensitization and integration, which eventually completes the cyclic process of inner growth.

The “awakened” faculties, namely present-moment-awareness or mindfulness, expressed through a calm, concentrative and open attention, allow a learner’s own sense of self, independence, autonomy and authenticity to surface and integrate, rebalancing one’s personality. MEI also positively affects students’ ability to mature within their group level through social intelligence, empathy and social resiliency, leading them to experience a sense of support and heartfelt community (3).

Stress, disability and adversity

Our day to day life often has us perusing the internet, reading and concentrating on the blast of information details our screens provide, while suddenly finding that we’ve lost track of everything else, including hunger or thirst. This mode of using our mental capacities overly engages the logical left-brain; it activates the fright-flight mechanism, adversely impacting the adrenal cortex and glands, producing stress (the chronic hyperarousal of the autonomic nervous system) – which in turn, brings down the body’s temperature and makes us increasingly insensitive to our environment. This is why when someone disturbs us in this state we often become irritated. Nowadays for our youth, this way of relating to reality is the norm rather than an exception. It is also a feature of persons on the Autism spectrum. The notion that social media makes our children antisocial is commonly examined these days. However, underlying this mode of relating is a deeply rooted conditioning that makes us identify with, and single out, a particular form/subject or activity. We refer to this as attachment. And when someone is trying to force us away from what we cling to, we experience irrational anger and the imagined rejection of the other person. When this reactive mode persists, stress accumulates, ranging from mild to extreme levels of discomfort that affect quality of life. [Research would need to conclude whether this process would also have a detrimental effect on gene-expression (DNA, telomeres), and the organization of neurological pathways (brain-plasticity)].

What keeps us dependent on this complex system of brain-mediated negative responses is our tendency to disconnect from the emotional right-brain, which seeks natural expression through the body. This means that over time a person becomes unaware of how biological responses are triggered and how they influence one towards discomfort, imbalance and disorder. These responses can be activated by a perceived impending danger, the “stimulus”. The adversity that these responses “react” to, may be a combination of physical and/or psychological distress, as well as environmental factors. In numerous cases, we’ve studied how these mechanisms dynamically elicit the resurfacing of trauma, while keeping its associated discomfort from being released.

Stages in the development of disorder

These internal response patterns associated with fear, sadness and or rejection may lead to loss of resiliency causing:

- Stage 1: Discomfort – imbalance arises in the most vulnerable part of the body or psychophysical function.

- Stage 2: Agitation – discomfort builds up in that part, putting psychophysical functions under pressure, causing agitation.

- Stage 3: Spreading – the discomfort spreads out and causes interference with other vulnerable parts and psychophysical functions.

- Stage 4: Fixation – the stress on specific parts and functions lead to physical and psychological fixation.

- Stage 5: Disability – symptoms such as mind-blanks, procrastination, ADHD and others may manifest.

- Stage 6: Adversity – disorders such as depression, suicidal tendencies, violence, addiction, PTSD or others may manifest.

If we are imagining this effect on children and students of all ages, their psychological and physical balance, including their self-image, sense of completeness, self-worth, self-esteem, and self-confidence, may be negatively affected by these progressive stages in the development of disorder. Excessive behaviors within the student community may further exacerbate the internal imbalance of students, leading to life-threatening situations, such as school violence, suicidal tendencies, drug, alcohol, game and other forms of addiction.

Bio-behavioral responses

Earlier we mentioned how stress is caused by bio-behavioral responses; these can either be natural or conditioned. The three bio-behavioral responses are:

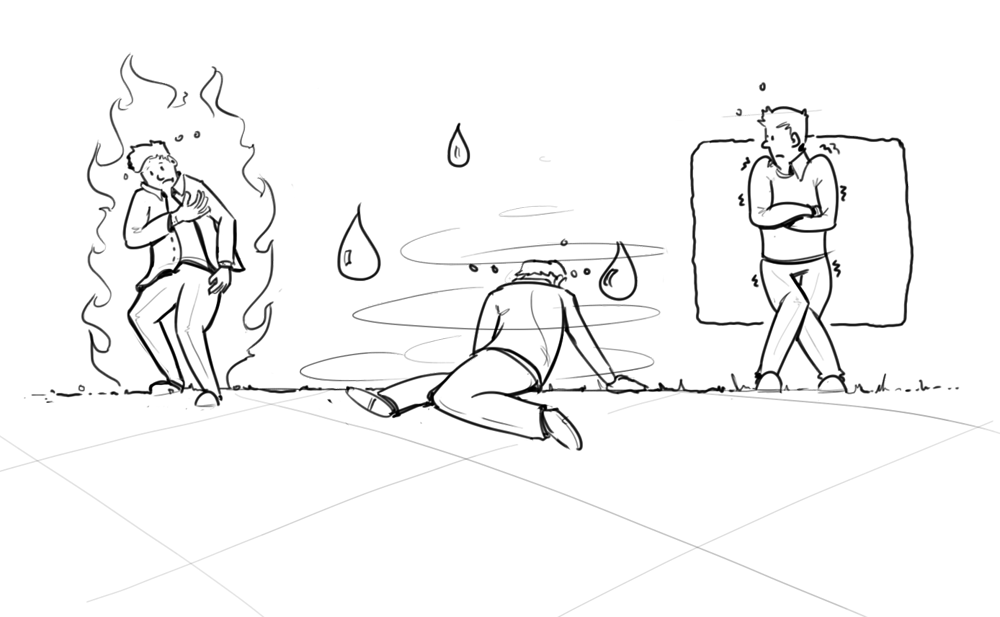

- Fear bio-response causes contraction and is a reaction from the nervous system.

- Sadness bio-response heats up (burns) and is a reaction from the metabolic system.

- Rejection bio-response suppresses (feels heavy) and is a reaction from the immune system.

When someone throws water in a person’s eyes, the nervous system naturally reacts by contracting or shutting the eyes. After a natural response, the body quickly reverts to a state of equilibrium. Natural responses are meant to keep one safe and balanced. However, when responses are conditioned through distress, they become reactive patterns and can often trigger differing levels of stress due to either real, remembered and/or imaginary causes. PTSD, for example, is comprised of accumulated conditioned responses. These conditioned responses are experienced through physical sensations and are part of a virtual-reality that’s mediated by the human brain and induced by memory; they are driven by the amygdalae through the limbic system. The limbic system responds by telling the body to begin preparing for defense action, our bodies flooded with hormones, we ready ourselves for impending danger. Projected memories associated with past emotions and biological responses, form the illusion of danger that is super-imposed onto the present reality. When remembering, visualizing or anticipating a situation, our human body responds as though one were currently participating in the actual event. This mistaken sense of reality affects all of us at varying degrees and determines the way we respond, behave and speak.

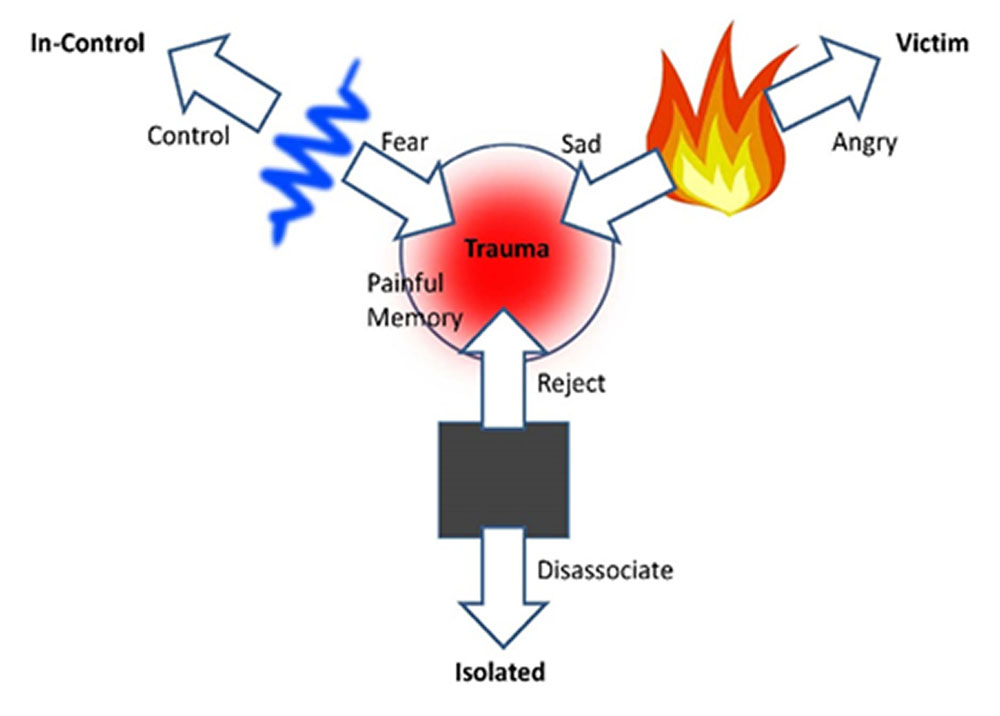

Humoral and mechanistic models of experience

In Indian Ayurveda (11), Greek Hippocratic medicine, and Jungian psychology, bio-behavioral responses are referred to as humors. The four humors or the four temperaments along with Jungian-based psychophysical humoral theory, have largely influenced the development of the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator among other tools. While in Sanskrit, the word dosha (humor) literally translates to a “tendency to become imbalanced”. There are superficial differences between the way these humors are explained by the various systems, but essentially, they point in the same direction. The author (Monsanto, 2010) has developed a synergistic model to interconnect these humoral theories. Ayurveda (11), which is the more evolved system, describes the bio-behavioral responses as ways in which our mind and body are designed to seek balance. But when they’re associated with fear-control, sadness-anger and rejection-disassociation (see below), they negatively affect us instead, at best making us feel uncomfortable, and at worst, developing into imbalance and disorder.

Modern medicine, neuroscience and the dominant forms of psychology, not fully understanding the fundamental energy-information–exchange process at the core of these responses, are at a loss attempting to understand it solely through the more structural and mechanistic Cartesian view of how the body and mind function.

Bio-behavioral responses unfold “homeo-dynamically” as a process at the most fundamental level, where they drive the development of health and disease, psychologically and physically altering the human structure and mechanics. The following contributions are noteworthy because they all point to the same underlying, relational and embodied energy-information-exchange model based on humoral theory.

- Carl Gustav Jung contributed some of the best-known concepts known to modern psychology, but most important for the current review is individuation (12). Individuation is the process that heals the whole person, both mentally and physically, transforming one’s psyche by bringing different aspects of the personal and the collective unconscious into the conscious.

- William James and Carl Lange contributed to psychology their Theory of Emotion (7). This theory states that our emotions are caused by interpretation (by the brain) of brain-mediated bodily reactions to events.

- Francisco Varella, et al. contributed the Theory of Embodied Cognition (8). Embodied cognition is the theory that many features of cognition, whether human or otherwise, are shaped by aspects of the entire organism. This draws from recent research in psychology, linguistics, cognitive science, dynamical systems, artificial intelligence, robotics, animal cognition, plant cognition and neurobiology.

- Many philosophers and psychologists such as James Beattie, Immanuel Kant, Arthur Schopenhauer, Søren Kierkegaard, etc., base themselves on humoral theory.

The humors, psychophysical temperaments, or bio-behavioral responses have been described and referenced for many centuries in the East and West and form the basis for how psychoanalysts and other branches of psychology, i.e. traditional, complementary and naturopathic medicine think about the development of the whole person. Instead of keeping them from contributing to science, why not invite them?

A human being has so many skins inside, covering the depths of the heart. We know so many things, but we don’t know ourselves! Why, thirty or forty skins or hides, as thick and hard as an ox’s or bear’s, cover the soul. Go into your own ground and learn to know yourself there.

Eckhart Tolle

The language of emotions, types of responses

This article starts with a quote from William James, wherein he describes how our aliveness contributes each and every experience and biological response to our personality. Next, we describe the linguistic characteristics of the bio-behavioral responses or humors.

The Language of Emotions refers to the following: bio-behavioral responses may be compared to the letters of the alphabet; letters (responses) form words (patterns); and the combination of words form sentences (stratagems); which connect with the meaning contained in what one perceives.

Responses: Let’s first start by enumerating the different responses:

- Fear — Control (electric) — linked with the operation of the nervous system. Its physical effects may be found in the table below. In the voice it produces a higher than normal throat sound. Speed is high. Low volume (fear) — High volume (control).

- Sadness — Anger (magnetic) — linked with the function of the metabolic system. Its physical effects may be found in the table below. It also affects the voice, producing a warm chest-abdominal sound. Speed is moderate. Low volume (sadness) — High volume (anger).

- Rejection — Disassociation (gravity) — linked with the function of the immune system. Its physical effects may be found in the table below. Produces a low bass sound resonating in the whole body. Speed is slow to very slow. Blocks expression. Low volume muffled sound (feeling rejected) — High volume with lots of bass (rejecting) — No sound (disassociating).

The chart below lists the types of experiences that are related to the expression of each response. This will help the reader in conducting his/her own first-person research. Most psychological theories have been formulated based on this way of exploring the subjective.

|

Fear — Control |

Sadness — Anger |

Rejection — Dissociation |

|

Fearful Alertness Tension, stiffness Cramp, Contraction Stinging, Sudden temp change Electric-like sensations Dizziness Restless Nausea Bloated (aversion) |

Victimized Vulnerability Burning Heat Prickly, Oversensitive Irritated Swollen Inflamed |

Isolated Dissociation Heavy Blocking Pressing Absent Lethargic Too much sleep Feeling tired all the time |

|

Powerlessness — All three responses combined as pain |

||

|

Free Will — absence of all three responses |

||

Table 1: describing the language of emotions alphabet

Patterns: Next let’s explore how different responses may combine into patterns:

- Responses may combine in sequences, one following the previous one in a specific logical order. Example: first you feel fear (tension) and after this you sense sadness (burning); this disappears, and you sense rejection (block).

- Responses may combine as layers, one response may lay on top of another. Example: you feel sadness (burning) and on top of this you may sense fear (tenseness).

Stratagems: The above-mentioned reactive patterns may combine into different stratagems. Each strategy may dominate a different area of experience relating to different meanings, embedded in how we interpret the internal or external trigger (memory, or imagination).

Organization of biological responses around distress

When a person is involved in an accident and experiences a rapid snapping motion of the neck, straining the muscles and structures around the spine, a whiplash injury most likely results. At first this injury may feel relatively normal; but, as the hours and days pass, the soreness, pain, burning, tenseness, and/or pressure may increase in and around the injured area. It is easily observable how these bio-responses (tension, burning and pressure) act relative to the physical distress. On the other hand, psychological distress or adversity especially in early life, seems to reprogram the neurological, metabolic and immune systems to respond as though there is a constant looming danger. This is called a coping mechanism, which is supposed to control our emotions through suppression and repression. We’ve observed this coping mechanism in real-time through various forms of assessment. Trauma resolution research by Dr. Peter Levine (13) and epigenetics research by Tie-Yuan Zhang and Michael J. Meaney (9) points in the same direction. Other situations that induce physical distress are viral and bacterial infection, poison, toxicity, and even anorexia, alcohol or other ways in which the body experiences high stress levels. Bio-responses similar to the ones experienced in an injury may be felt in these situations, but the patterns will vary. Below are the various types of distress, and how they may appear in combination (compounding) or create interference patterns.

Strength: the strength of the bio-responses depends on the severity of the distress.

Types of distress

Similarities between physical and psychological distress may be observed. As smoke is indicative of fire, so are the biological responses indicative of the underlying distress. The way in which and where in the body biological responses manifest, points to the type of distress that they relate to. How these responses unfold sequentially and/or are layered, how they’re patterned, if they manifest superficially or at a deeper level — is different for each type of distress. The following is a short description of the various types of distress.

Physical distress:

- Accidental trauma is a physical distress that is arranged at the surface of the body, constantly reminding one of its presence. Biological responses gradually cause us to feel more uncomfortable, both physically and psychologically. The distress has mostly a long cycle of healing.

- Environmentally induced distress, such as through viruses or bacteria, targets particular organs, anatomical structures and or physiological functions. Bio-responses may be felt internally within those organs and structures. This distress has mostly a medium cycle of healing.

- Alcohol, drug and opioid induced distress primarily targets the nervous system, liver, kidneys and other vital organs. This has mostly a short cycle of healing.

- Dietary habit induced distress primarily targets the digestive tract. Think of eating too much spicy, junk or unctuous food, anorexia, bulimia, and other eating disorders. This may have a medium to long cycle of healing.

Psychological distress:

- Psychological distress lies deeper inside the body and only surfaces in certain situations when triggered. And when an emotional distress shows up, bio-responses instantly appear in and around the emotionally affected area. The cycle of healing depends on awareness, discernment and the desire for healing, leading to inner growth. The healing cycle depends on this.

Compounding distress:

- The compounding of physical and psychological distress allows the combination of all traumas, distress, associated painful memories and bio-behavioral responses to jointly express according to their own separate and interference patterns. Example: the responses associated with a psychological distress may express through a physical or another psychological trauma.

- Most addictions result from a compounding of various psychological distresses, weakening the mind’s will power and the body’s vitality and stress resistance. The substances used, further damage organs, such as the liver, adrenals and kidneys.

- The healing cycle of compounded distress is considerably longer and calls for greater levels of commitment and Mindful Emotional Intelligence.

Post-traumatic-stress:

- Post-traumatic stress may be experienced in mild to extreme forms depending on the severity of the pain experienced. In a mild form, psychological function will be mildly impaired. Whereas in severe cases, psychological function will be equally impaired.

Case: Rebecca had a bad fall and bruised her hip. After a few weeks the discomfort had completely disappeared, and she had regained full mobility. Recently she had an emotional challenging experience with her step-mother that made her feel sad and powerless. She had mild symptoms of depression and felt a resurfacing of the pain in the same hip that she’d injured months before. So, she had both the hip-pain and the psychological discomfort. As she internally resolved the emotional experience, both the psychological discomfort and the pain in the hip disappeared. This is an example of compounding — interference patterns.

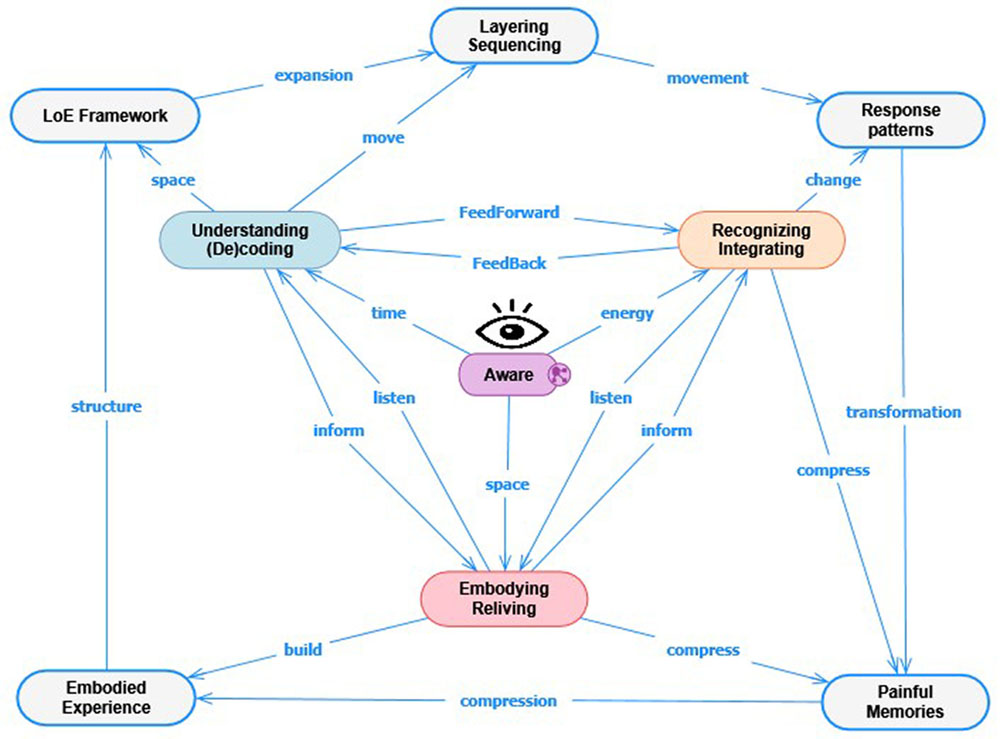

Decoding, recognizing and integrating

Recognizing every response, pattern and strategy through the Language of Emotions framework helps to unveil and integrate unconscious painful memories. The following models the dynamic integration process that can affect any one of more that forty-two (42) anatomical regions from head to toe.

This process supports one in cultivating greater levels of awareness and discernment, making one mindful of nine specific domains of experience (10). Greater levels of well-being result from integration within and among these domains (10):

- Transpersonal integration — A person senses a connection with everything, from time, space, energy, to everything else.

- Temporal integration — Integrating how we psychologically map time in past-present-future.

- Consciousness integration — Integration of mental, emotional, physical, self-relational, social relational, and feedback relational (inner learning) awareness.

- Bilateral integration — Integration of left-brain/right-body (linear/logical) and right-brain/left-body (nonlinear/emotional).

- Vertical integration — Integration of top and bottom parts of the body; learning how to be grounded in one’s own body.

- State integration — Cultivating an open and neutral attitude towards feeling positive as well as towards negative emotions.

- Memory integration — Integration of the past and future into the present; making implicit memories (past impressions) explicit through embodied experience.

- Narrative integration — How you speak about what you have experienced and what you currently experience makes sense and becomes verbally explicit.

- Interpersonal integration — Wholeheartedly accept the differences between oneself and others; leads to heart-brain attunement.

During the healing cycle presented in the following section, the above areas of integration will simultaneously reference a mindfully aware and discerning mental state.

The healing cycle

The following cycle describes the various stages from the preparation, assessment, guidance, desensitization, catharsis and ultimately the expansion of maturity, awareness, discernment, and the alignment and connection of mind and body:

- Assurance — Gives comfort.

- Assessment — First-person observation of the process, using discernment to assess progress.

- Feedback — Describe the process and evolving patterns in real-time.

- Motivation — The inner drive to proceed through the process.

- Guidance — Direction on how to navigate internally and subjectively deal with responses and evolving patterns at the root of objective experience.

- Education — Subjectively understand how responses and evolving patterns influence how we feel, relate and communicate.

- Modification — The course of action on subjective levels is instantly changed through being aware and discerning.

- Dehypnotizing — The power of illusion that patterns project onto our present reality is weakened.

- Desensitizing — The inner responses lose their power of influence.

- Catharsis — A transformational recalibration and cleansing takes place, clearing inner felt negative emotions and confusion.

- Satisfying — Space opens up for a genuine sense of peace.

- Expansion — Sinking into a sense of being greater than yourself.

The above cycle inevitably leads to a complete reversal of the stages of development of disorder, which results in balance and health on all levels. A team of researchers involved in Brown University’s Dark Knight (of the soul) project, has been interested in studying the “negative” effects of the practice of mindfulness and other contemplative practices. Their study refers to those practitioners who seem unable to integrate the bio-behavioral effects that may surface during contemplative practice. This leads to psychological crises (14). These effects include tension, involuntary movement, anxiousness and cognitive impairment. The duration may vary from short to periods of over a decade. Through Applied Self-Assessment Psychology, students can be internally guided to thoroughly examine these bio-behavioral responses associated with fear, sadness and or rejection. This internal and sometimes intersubjective process desensitizes mentioned responses, reducing cognitive impairment, to a level where further integration aligns all systems (neurological, metabolic and immune), restoring balance on all levels (psychological and biological).

Being reminded of our “wholeness”

In our modern society, we are accustomed to thinking that we’re not good enough and that we constantly need to look for and fix or suppress whatever is broken within us. This belief keeps us in the dark about how to autoregulate and metabolize emotions. An example of social conditioning is the notion that we shouldn’t cry, and that one should always think positively. On top of this, reward systems create division and a sense of not being good enough. Our minds are conditioned with information, assumptions and beliefs that keep us oblivious about who we are and what we really feel emotionally and sense physically. We have come up with so many new therapies and practices, life-style advice, do’s and don’ts, policies and regulations, as solutions for bringing life under control.

Instead of trying to impose fixes to “problems” in ourselves and others, the inductive learning-by-doing approach we teach, assists participants in regaining access to their inborn capacity to recognize and metabolize unresolved experiences. It is easy, works fast and removes dependence on other persons, situations or substances, because it works from the inside-out. Mindful Emotional Intelligence is the learning objective. However, motivation and commitment are essential to one’s own process of maturation.

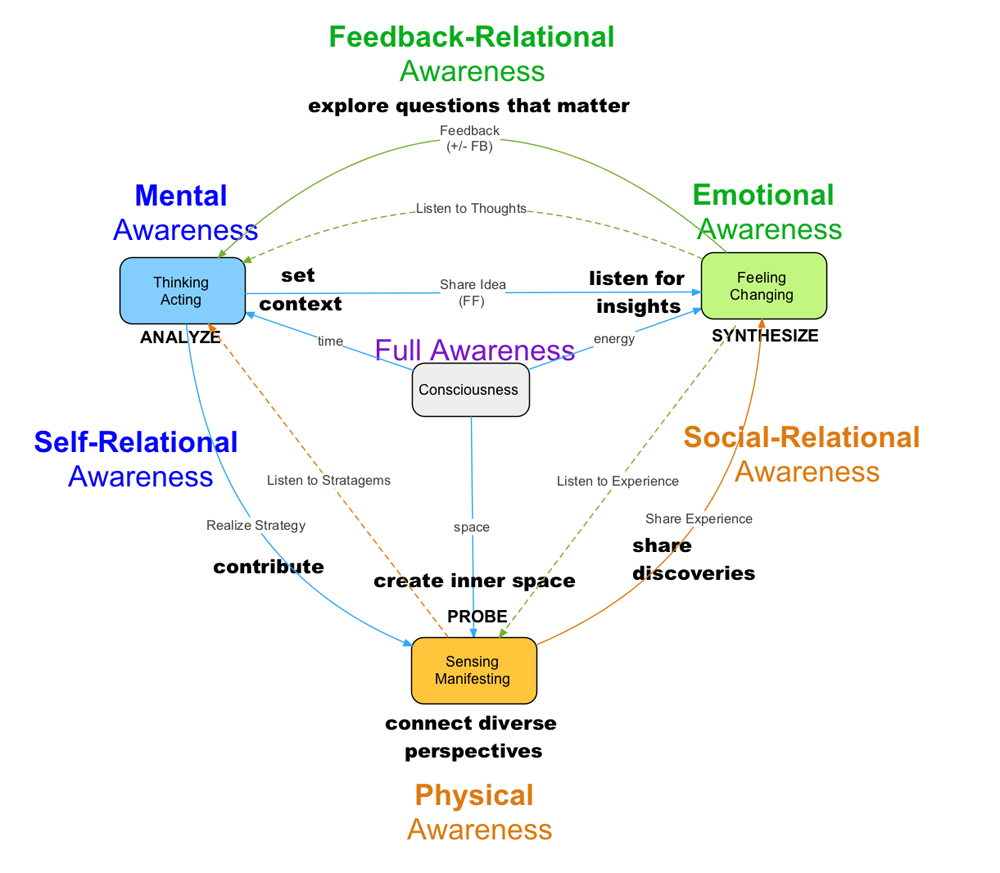

Mindful emotional intelligence-based pedagogy

As part of the pedagogical process, the mentor who can be a teacher, attunes to the student(s) via a dynamic form of bio-behavioral assessment. Through a system of internal feedback, information about what the students experience physically and emotionally is revealed. This in turn supports and enhances mindful discernment, self-assessment, emotional self-regulation, intersubjectivity, dialogue and group-learning. As a result, the student is awakened to his/her own identity through a state of discerning mindful awareness, relative to which the student’s mental, emotional, physical, self-relational, social-relational, and feedback-relational awareness are (re)aligned and (re)integrated. The student develops a level of mindful emotional intelligence, sensitivity and awareness that constantly evoke self-directedness, self-regulation and peer-to-peer exchange.

Student mentors

Because of the sense of genuine community that this process brings about, learners who previously suffered from behavioral “problems” such as shyness, anxiety, procrastination, and or learning disabilities, are likely to come out of their isolation and pay forward what they’ve learned, in a natural and co-conscious way. The process takes the student to a new level, where s/he may be trained as a student mentor, paying forward and contributing to the maturation process of fellow students in need of assistance. This is such an empowering space to be in. This sense of belonging inspires and has the potential to initiate and accelerate maturation and inner growth of many students as well as their circle of influence, namely fellow-students, friends and family.

Mindful emotional intelligence inventory

While modern psychology looks at the expression of emotions, and biochemistry investigates concrete biochemical composition, we probe the fundamental mechanisms from which our body and mind explicitly and synchronistically respond to underlying distress and the immediate world outside. Because the human mind and body are open systems, the environment, lifestyle, and habitual patterns easily influence them towards imbalance. The only way to sustainably cause these mechanisms to behave in accordance with awareness or mindfulness as a reference, is by accessing an internally aware understanding (4) that translates their expression. This is learned through internal assessment and feedback, which is part of the mentoring and self-assessment process in ASAP. In the past decades, the authors have explored how these bio-behavioral mechanisms are autonomously recalibrated and rebalanced within mind and body by continually cross-referencing mentioned internal understanding and an unchanging meta-awareness, also referred to as mindfulness (4). The authors have also observed how Mindful Emotional Intelligence guides psychological and biological systems towards order, referred to as self-regulation. A complementary tool on the path has been MEI-i or Mindful Emotional Intelligence Inventory; it is helpful in that it describes how far a student is capable of internally facilitating such underlying processes of integration.

What is mindfully recognized within our subjective world through emotional intelligence, makes our experience of self, much more integrated and complete. It positively affects among other things one’s self-image, emotional and physical balance, leading to greater levels of subjective well-being (SWB). Mentoring and learning programs enhance the capacity to recognize subtler levels within one’s self, integrating experiences that span both mind and body to achieve even greater levels of emotional and physical alignment, and overall wellness. In this process “learning from the inside-out” is continually associated with one’s personal and professional goals. The Mindful Emotional Intelligence Inventory or MEI-i measures different aspects that relate to one’s ability to mindfully recognize what types of experiences unfold subjectively. Special attention is brought to differentiating between different bio-responses, how they unfold as patterns, unlocking painful memories, and affecting how we respond physically, behaviorally and emotionally. This inventory also helps reveal our level of awareness and level of embodying experience. Further, the MEI-I, that is facilitator-led, complements the Consciousness Quotient Inventory or CQ-I, described further below.

Consciousness Quotient inventory

The aforementioned MEI-i can also be cross-referenced with the CQ-i — Consciousness Quotient Inventory (5), which will reveal variables such as:

- Spiritual CQ (full awareness) — Being mindful

- Cognitive CQ (mental awareness) — Aware of how you think

- Emotional CQ (emotional awareness) — Aware of how you feel

- Physical CQ (physical awareness) — Aware of what you sense

- Self CQ (self-relational awareness) — Aware of relationship with yourself

- Social Relational CQ (social relational awareness) — Aware of relationship with others

- Inner Growth CQ (feedback-relational awareness) — Aware of feedback that serves learning

The role of mindful emotional intelligence in education

As the self-guided process based on MEI advances, a stable sense of being mindfully aware becomes the base from where students recognize and release negative bio-behavioral responses and associated emotional responses, behaviors, and imbalances. Using an integrative language-of-emotions framework, they identify and qualify dynamic states of mind, facilitating more authentic expression of self. Rolling out the facilitation of such a process within existing educational environments requires a holistic and multi-phase learning-by-doing approach:

- Management — First inform and train the management team

- Faculty — Offer faculty-development training and personal mentoring

- Students — Deliver programs, lectures, workshops and credit-bearing courses to students

- Parents — Offer similar social emotional learning programs to parent-teacher associations (PTA)

- Community — Offer community training led by faculty-student-parent facilitators

This may be co-realized with a program, school, or institute’s management, faculty, and students through exploring how MEI can be integrated in curricula, culture, and policies. Furthermore, evidence-based research can be designed to describe the impact of implementing both ASAP and MEI over a multi-year period, ensuring its effective realization within Applied Social Emotional Learning processes.

Traditional pedagogical approaches overemphasize the development of identifying and concentrating, information-retention and logical-mathematical thinking that create imbalances within learners. This left-brain dominant approach has caused a reduction in the effectiveness of a student’s ability to learn, be mindful or discerning, as early as preschool. We believe that Applied Social Emotional Learning needs to be introduced into our schools and be designed to restore inner balance and grow the capacity for educators and learners to transparently communicate across their subjective and objective realities, leading to greater levels of trust and integrity. In the past few years, SEL has been touted as the next educational frontier that is going to transform the lives of teachers and students, but actual implementation of an integral SEL approach is still missing.

Changing the status quo

At present, modern science and its impact on global community, is increasingly experiencing the limitations of its structural-mechanistic approach to dealing with challenges that relate to those processes that take place within each one of us. Think of the millions of people who are suffering from stress-related disorders such as PTSD, depression, digestive issues, and other neurobiological complications. Think of the social division and unrest that has humanity in its sway. These are expressions of our internal levels of stress — division and unrest associated with fear/control, sadness/anger, and rejection/disassociation, fed by our individual and collective trauma. Our modern society tends to deal with these challenges by addressing the part within the structure that is broken, which unfortunately tends to disrupt the function of the system as a whole. Based on this mindset, most current policies and therapies try to manage the “affected behavioral problem” through “action-oriented” strategies. These socio-scientific norms address the surface symptoms but are not equipped with the wisdom and tools to assess, inform, and guide towards rebalancing subjective processes.

Humanity is in a crisis, and policy-makers, researchers, and scientists are still trying to figure out how to solve these crises from the same mindset that has created them.

Understanding what is needed to change the status quo, the authors urgently call for action to validate and implement relational and embodied, energy-information-exchange models, which in their application unite scientific, traditional and wisdom-based systems; it is of vital importance that we synergize these different paradigms in education. Too often industrial research tends to be biased towards monetization, and not towards restoring psychological and physical wellness. In essence, a gravitational shift is needed towards developing a holistic science, in which transdisciplinary environments guide researchers and social stakeholders to both objective and subjective approaches to the study of life. This would be a solid first step towards integrating and evolving current and outdated systems, for the greater purpose of solving our current global crisis.

Below, we explain our vision in greater detail, and discuss its potential across disciplines.

The future of ASAP and MEI

Based on our experience, we realize that the horizons for this work are expanding in number and application. Imagine, growing up able to track your nervous system and self-regulate when unexpected circumstances throw your life into chaos. Chaos is part of the nature of being human and alive. We should have the supporting competencies to bring order to our lives, using innate capacities for self–maintenance. We believe our children should learn this in their schools, in youth centers and academic institutes, which is where they have a chance to develop such supporting competencies that help them develop a healthy relationship with the immediate world outside. Adapting ASAP to help children, teens, and young adults to understand and integrate what they feel, including their emotions, would support them in internally navigating crises; minimizing triggering and projection; and differentiating between natural and conditioned bio-behavioral responses. The personal resiliency that results from intelligent adaptability and interconnection, supports integrity of all biological systems (mental faculties included) leading to flow. At the Mindful Connection Institute, we aspire to develop an age-sensitive K-12 curriculum that supports developing these competencies in public, private and alternative educational institutions.

We also envision bringing Mindful Emotional Intelligence training to hospitals, hospices, crisis intervention centers, and disaster response teams, to train staff members in supporting clients/patients who are desperately in need of tackling the effects of distress on both physical and mental-emotional levels. As researchers and educators, we want to offer a more effective way to assess and address (early childhood) distress, as the root cause of a lot of suffering, illnesses and learning disabilities. We envision living from a healthier and more complete perspective, rather than carry around disconnected pieces of identity that relate to unresolved and unintegrated experiences.

In future research, we also seek further scientific validation of ASAP and its self-assessment model, theory and practice, within any given environment and through interdisciplinary application. We wish to contribute not only to the inner growth of faculty and students at schools and institutes, but also to the growth and healing of anyone interested in becoming more self-directed, socially resilient, emotionally mature and authentic.

A larger vision

We are excited about the possibilities and opportunities that this work provides to our global society and envision Applied Self-Assessment Psychology (ASAP) and Mindful Emotional Intelligence (MEI) as stepping stones into uncharted territory. Within Education we have a chance to truly begin to shift our perspectives towards transformative, learning-centered education in which we spend less in assimilating knowledge and repairing ourselves and more in truly knowing ourselves, discovering our potential, and as a result, evolving our global society and the collective consciousness of our planet. We envision evolving our humanity to a level where it is at peace with itself.

References

- Maturana, H.R. and F.J. Varela (1980). “The cognitive process”. Autopoiesis and cognition: The realization of the living. Dordrecht, Boston, London: D. Reidel Publishing Company. google.com/books?id=nVmcN9Ja68kC&pg=PA13

- Thompson, E. (2010). “Chapter 1: The enactive approach”. Mind in life: Biology, phenomenology, and the sciences of mind (pdf). Cambridge, Massachussets, London: Harvard University Press. p. 3-57 ucsd.edu/MCA/Mail/xmcamail.2012_03.dir/pdf3okBxYPBXw.pdf

- Brumbaugh, R. S. (1982). Whitehead, Process Philosophy, and Education. Albany NY: SUNY Press. robert-brumbaugh-towards-a-process-philosophy-of-education/

- Monsanto, C. & Lakshmanan, S. (2015). Awareness and Discernment Lead to Homeostatic Integration: A Research on The Mechanisms of Psychoneuroimmunology in Ayurveda. Ayurvedic. DOI: 10.14259/av.v2i1.170. com/index.php/AV/article/view/170

- Brazdau, O. and Mihai, C. (2011) “The Consciousness Quotient: a new predictor of the students’ academic performance”. Elsevier Procedia Social, 11, 245–250. sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1877042811000723

- Monsanto, C. (2016). Mindful Emotional Intelligence Inventory. Retrieved on 8th December 2017 from com/assessment.html

- Popova, M. (2011). What is an emotion, William James’ revolutionary 1884 theory of how our bodies affect our feelings. Retrieved on 8th December 2017 from what-is-an-emotion-william-james

- McNerney, S. (2011). A brief guide to embodied cognition. Retrieved on 8th December 2017 from a-brief-guide-to-embodied-cognition-why-you-are-not-your-brain

- Zhang TY, Meaney MJ (2010). Epigenetics and the environmental regulation of the genome and its function. Annu Rev Psychol 61: 439–466 C431-433.

- Daniel Siegel (2012). Pocket Guide to Interpersonal Neurobiology, Norton Series. http://bit.ly/dansiegel_pocketguide

- Ministry of AYUSH (2014). Description of Ayurveda. Retrieved on January 8, 2018. http://ayush.gov.in/about-the-systems/ayurveda

- Carl Gustav Jung (1875-1961). Carl Jung — Wikipedia article. Retrieved on January 9, 2018. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carl_Jung

- Levine, P. (2015). Trauma and Memory: Brain and Body in a Search for the Living Past: A Practical Guide for Understanding and Working with Traumatic Memory. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books, Lyons: ERGOS Institute Press. https://books.google.com/books?isbn=1583949941

- Britton W., Lindahl J. et al. (2017). The varieties of contemplative experience: A mixed-methods study of meditation-related challenges in Western Buddhists. Plos One. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0176239