Mitra Muijen

On Davidson’s Theory: A defense against Watson’s criticism

Weakness of will presents a challenge to those who are looking to preserve the concept. For how can one accept the idea that intentional acts tailor to the agent’s better judgment, while maintaining the possibility of intentionally acting to the contrary? Philosopher Donald Davidson tries to solve the problem by postulating a logical disconnection between conditional and unconditional judgments. Since weakness of will only applies to the former, and the ‘principle of intentionality’ to the latter, the paradox seems to be dealt with.

Gary Watson, a skeptic with regards to weakness of will, is not convinced however. Although he employs Davidson’s essay to highlight the troubles of Socratic skepticism, he criticizes the philosopher’s proposed solution to the apparent paradox. In this essay, I will defend Davidson’s work by evaluating Watson’s critique, in order to dismiss it as ultimately unconvincing.

In the first section, Davidson’s account concerning weakness of will shall be outlined. Afterwards, in the second section, I will introduce Watson’s nonsocratic skepticism, together with his three critical questions in response to Davidson’s theory. Special attention will be given to his third point, for it is the only one he elaborates on. Replies to these questions, lastly, shall be provided in the third section.

Davidson’s Account concerning Weakness of Will

In his 1970 essay How is Weakness of Will Possible?, philosopher Donald Davidson attempts to reconcile two seemingly contradictory, yet plausible doctrines; namely

- that incontinent actions do exist, and

- that intentional acts conform to what the agent judges to be best.

Incontinence, here, i.e. weakness of will, refers to the phenomenon of intentionally acting against one’s all-things-considered, better judgment. Davidson (2001) characterizes such actions as follows:

“In doing x an agent acts incontinently if and only if: (a) the agent does x intentionally; (b) the agent believes there is an alternative action y open to him; and (c) the agent judges that, all things considered, it would be better to do y than to do x.” (p. 22).

The assertion that there are incontinent actions (1) shall from now on be referred to as premise 3, or P3. Meanwhile, the latter of the two aforementioned doctrines (2) follows directly from two other premises, P1 and P2:

“P1. If an agent wants to do x more than he wants to do y and he believes himself free to do either x or y, then he will intentionally do x if he does either x or y intentionally.”

“P2. If an agent judges that it would be better to do x than to do y, then he wants to do x more than he wants to do y.” (p. 23).

The incontinence paradox

Davidson accepts all three premises, as he believes each to be self-evident. The problem however, is that P1 and P2 together seem to falsify P3. For if an agent ultimately favors y over x (criterium (c) in his characterization of incontinent action), then, following P1 and P2’s reasoning, it seems impossible to do x intentionally (criterium (a)). This, I shall refer to as the ‘incontinence-paradox.’ What Davidson proposes, then, is that the apparent contradiction is in fact a false one, and that none of the premises ought to be given up after all.

Davidson’s crucial move is to postulate a logical disconnection between unconditional principles, such as ‘it is better to do x than to do y,’ and the agent’s subsequent judgment in the light of all relevant considerations, i.e. the agent’s conditional judgment (Davidson, 2001, p. 36-39).

Example: the act of fornication

I might, for example, prima facie condemn the act of fornication on moral grounds, and yet be attracted to it for the sake of pleasure.

However, my subsequent decision to refrain from fornication does not logically follow from any of these competing principles. It is the result, rather, of careful deliberation involving all relevant and available considerations. This includes, at the very least, the prima-facie principles ‘refraining from fornication is better than the act of fornication’ and ‘the act of fornication is better than refraining from fornication.’

The merit of this logical disconnection is that it removes any logical conflict between conditional and unconditional principles. It is simply impossible, that is, to infer anything definitive about some conditional judgment, simply from the preceding set of unconditional principles.

After all, ‘x is better than y’ is logically separate from ‘x is better than y, all things considered.’ In other words, ‘x is better than y, all things considered’ does not imply ‘x is better than y.’ And since P1 and P2 only apply to unconditional statements, and P1 to conditional judgments, any apparent paradox has now been resolved.

The only question remaining is whether incontinence is still plausible on this account. In other words: “How is it possible for a man to judge that a is better than b on the grounds that r and yet not judge that a is better than b, when r is the sum of all that seems relevant to him?” (Davidson, 2001, p. 40).

Davidson deals with this concern by suggesting that an agent who does incontinent action x for reason r, has a better reason r’ (which includes r) to do y. Similarly, if such a reason r’ is absent, and the agent judges there to be no better action than x, we may speak of continence.

In short, the agent simply acts irrationally in the event of incontinence; only when he judges on the basis of all relevant evidence, can we speak of him as being rational (Davidson, 2001, p. 39-42).

Watson’s Questions

Philosopher Gary Watson is a proponent of non-Socratic skepticism when it comes to weakness of will. While he accepts the possibility of an agent knowingly acting against his better judgment, he rejects the idea that he does so freely. It is a form, rather, of psychological compulsion.

The errors of socratism

Watson employs Davidson’s work in his essay Skepticism about Weakness of Will to help him isolate the errors of socratism — another form of skepticism, which deems weakness of will entirely impossible (Watson, 1977, p. 319).

That is, on the Socratic assumption that an agent desires and pursues what he judges to be best (P1 and P2), intentionally acting to the contrary involves a straight contradiction. The agent would simultaneously believe some course of action to be best, while believing it not to be best (P and -P). Those who are said to be weak-willed, Socrates would argue, simply confuse the more immediate good with the greater good.

Although Davidson’s work helps Watson in making the Socratic position more precise, he is ultimately unconvinced by the philosopher’s own solution to the apparent paradox. Watson voices his criticism in the form of three critical questions, which he believes ought to be accounted for:

“First, is the distinction between a judgment all-things-considered and an unqualified or unconditional judgment sound? … Second, even if this distinction were made out, is there not equally good reason to think that people act contrary to their unqualified or unconditional judgments, as there is to think that people act contrary to their all-things-considered judgments? … Third, are P1 and P2 true?” p. 319.

Watson’s first two questions, on the one hand, challenge the core assumption underpinning Davidson’s solution, namely that there is in fact a logical disconnection between conditional and unconditional judgments.

The third question, on the other hand, casts doubt on the entire essay’s relevance. For if P1 and P2 are untrue, the existence of incontinence does not generate any (apparent) paradox. Thus, for Davidson’s article not to be dismissed, all three points ought to be adequately dealt with.

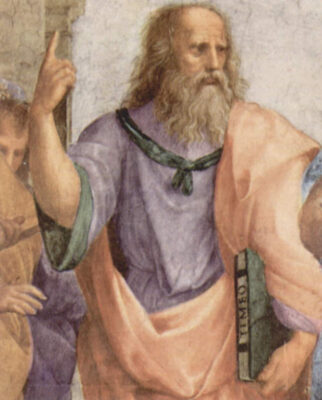

The rational and emotional part of the soul

Watson does not elaborate further on the first two questions — I shall return to those in the next section. He does, however, dwell on the last, concerning the truth of the premises P1 and P2. Plato, Watson argues, already questioned the Socratic doctrine’s merit. Consequently, rather than adopting the belief that our better judgment produces motivation, Plato posited the existence of two separate sources of motivation: the rational part of the soul, which produces judgments of value, and its non-rational counterpart, which produces desires of appetite and emotion. It is precisely when these desires come into conflict, that we act against our better judgment. Plato, in other words, rejected P2 by separating our motivation from what we judge to be best (Watson, 1977, p. 319-320).

Watson accepts the platonic view that our desires do not necessarily depend on our moral evaluation. One might, for example, have desires of hunger and sex, without having to praise the associated actions. And accepting this as a genuine possibility, entails a rejection of socratism. Davidson’s premises P1 and P2 can be separated in a similar manner, Watson argues (Watson, 1977, p. 320-321). That is, P1 expresses ‘wanting x more than y’ in the sense of motivation, whereas P2 expresses ‘wanting x more than y’ in terms of value. An agent might want something P1-wise, yet not P2-wise, while wanting another thing P2-wise, yet not P1-wise. In short, there’s nothing that necessarily connects these premises, and indeed all the more reason to keep them separated.

Replies

Question 1: on (un)conditional judgements

Watson’s first critical question addresses the soundness of the distinction between conditional and unconditional judgments. Let’s call it the ‘conditional-unconditional distinction.’ “It might well be supposed,” Watson states, “that an all-things-considered [conditional]judgment is precisely an unqualified [unconditional]judgment made on the basis of all considerations thought relevant by the agent.” (Watson, 1977, p. 319. It seems, then, that he denies any qualitative difference between ‘x is better than y’ and ‘x is better than y, all things considered.’ The phrase ‘all things considered,’ we may assume, has simply been added as if it were a mere mathematical variable.

Unconditional judgments, unlike their counterparts, can never cause behavior

But that hardly seems to be the case in Davidson’s work. The main distinction he himself appears to hint at is the fact that conditional judgments are truly practical in their issue, while unconditional judgments are practical only in their subject. Put differently: “Reasoning that stops at conditional judgements … is practical only in its subject, not in its issue.” (Davidson, 2001, p. 39). In other words: unconditional judgments can, unlike their counterparts, never cause behavior. Which leads me to believe that unconditional judgments can be viewed (metaphysically speaking) as a kind of theoretical entities, preceding our practical judgments. And if that is the case, denying any qualitative difference between the two seems wrong to me.

In order to clarify my point, I propose to make an analogy with Plato’s theory of Forms.[4]I realize that I am going beyond Davidson’s own words by doing that, but I think it shall be helpful for understanding the situation. For those unfamiliar with the theory, author Andrew Mason (2014, p. 29) defines the Platonic Form as follows:

“A Form, for Plato, is in the first place the nature or essence shared by many things, when the same term is rightly applied to them; to know, for instance, the Form of the good is to know what goodness is – to know the essence that all good things have in common.”

Form itself can never truly be captured — it can only ever be manifested in the objects

A Form can be thought of as a universal expressed in every object of a certain kind. The interesting thing, though, is that the form itself can never truly be captured — it can only ever be manifested in the objects, without itself being one. And yet, all objects of a certain kind presuppose their ‘theoretical base.’

The situation with conditional and unconditional judgments, as I have described it here, can be viewed in a similar manner: just like the actual objects and their forms, all conditional (practical) judgments are essentially derived from their unconditional counterparts, and are as such grounded in a kind of theoretical base.

This section admittedly contains a lot of speculation on the nature of both conditional and unconditional judgments, and undoubtedly a lot more work must be done to make my hypotheses more watertight. What I hope to have shown, though, is the need for nuance when it comes to Davidson’s conditional-unconditional distinction. Watson’s question leaves in that respect much to be desired.

Question 2: on acting against unconditional judgements

If the first question is adequately dealt with, and we may indeed suppose there is a distinction between conditional and unconditional judgments, is Davidson’s solution out of trouble then? Watson’s second question suggests otherwise.

Even if we suppose a distinction between conditional and unconditional judgments, he argues, there is still reason to believe that people can act not only against the former, but also against the latter. In other words, it seems at least possible for an agent to act against his prima facie, unconditional judgments. And yet, “Davidson’s theses entail that this is impossible.” (Watson, 1977, p. 319).

The possibility of incontinence requires competition between two opposing judgments — say, doing x and doing –x. This means that both x and –x must be granted prima-facie reason to be acted upon. Consequently, precisely because of these attributes, there is no contradiction between the two.

The process of weighing judgments

Now for an agent to act either rightly or wrongly, both must be juxtaposed to leave room for a ‘process of weighing considerations.’

Thus, x and ¬x must both be considered in order for the agent to judge one superior to the other. “It is not enough to know the reasons on each side: he must know how they add up.” (Davidson, 2001, p. 36). Only then can we act either according to or against our better judgment, i.e. our all-things-considered judgment. What would it mean, then, to act contrary to our unconditional judgments instead?

Does it make any sense to act contrary to one’s unconditional judgment?

At first glance, acting contrary to one’s unconditional judgment sounds obviously possible. I can imagine, after all, having an unconditional judgment that says ‘y is better than x’, while doing x — and that doesn’t seem to generate any contradictions. I believe, however, that the question itself is deceiving; better formulated, it goes something like this: does it make any sense to act contrary to one’s unconditional judgment? And the answer to that question is a resounding “no.”

Take an all-things-considered judgment (J), featuring considerations x and ¬x as shown below:

x and -x

J

No matter what the agent ends up doing, his judgment will always be in line with one unconditional judgment, and opposed to another (nota bene, both x and ¬x enter the deliberation process in juxtaposition). Furthermore, these judgments are neutral in a sense, since both are prima facie good, or better than the other.

Which implies that none is better, absolutely speaking. In other words, there is no ‘right’ judgment, other than his better judgment J, the agent can act contrary to. He is simply in line with one and not with the other. So although acting contrary to one’s unconditional judgment is technically possible, it simply does not make any sense.

Question 3 on the incontinence paradox

Watson’s last question, concerning the truth of P1 and P2, is I believe the most important of the three. For if Watson is right, and the two premises can indeed be separated based on their dissimilar senses of ‘wanting more,’ the incontinence-paradox simply disappears. It isn’t paradoxical at all to say that an agent does incontinent action x because he prefers it over y in the sense of motivation (P1-wise), while judging y to be better in the sense of value (P2-wise). He still does x intentionally, and he still believes y to be better on the whole — albeit in an evaluative sense. In short, the agent still acts incontinently, without generating any paradox.

The problem, however, is that Davidson’s essay revolves around precisely this paradox; it is the catalyst, so to say, that generates his entire argument. So if Watson’s rejection of socratism is conclusive enough, the essay surely loses much of its relevance. And in order to avoid that, credence must be given to the truth of P1 and P2.

Socrates’ denial of weakness of will

Since these premises essentially summarize Socrates’ denial of weakness of will, it might be helpful to review his argument before moving on. Fortunately, philosopher Thomas Gardner provides a concise paraphrased version (Garder, 2002, p. 192-196). Socrates, Gardner explains, starts off by assuming the possibility of incontinence, which he defines as follows:

“Knowing that action x is worse than action y, one chooses to perform x because one is overcome by its pleasures.” p. 193.

If an agent knows one action to be worse than another, he correctly realizes that the former generates less pleasure on the whole than the latter. Thus, when the agent chooses x over y, he is basically willing to accept a greater amount of displeasure on the whole for the sake of securing x’s goods. And that conclusion is absurd, Socrates thinks, precisely because it contradicts his law-like view that when one judges the overall pleasure of a certain action y to be greater than the overall pleasure of another action x, he must opt for y. Ergo, weakness of will is impossible.

“ … we may think x better, yet want y more.”

Davidson (2001, p. 23) himself says a number of things too about P1 and P2 in his essay — starting with his assertion that both premises are in fact self-evident. Still, a more true defense of the doctrine can be found in his discussion of rejecting P2 as a way of dealing with the incontinence-paradox.

“It seems obvious enough, after all, that we may think x better, yet want y more.”

Davidson, 2001, p. 23)

What Davidson realizes here, is that the premise in question can easily be interpreted as suggesting that ‘ought’ implies ‘want.’ And that claim seems obviously false, since our desires often deviate from what we think we ought to do. For instance, I might want to lay on the couch watching television, while thinking that I ought to finish writing my essay. Watson, I believe, takes this exact route; and Davidson (2001, p. 23) even credits Plato with rejecting P2 in such a way (Davidson, 2001, p. 23).

Although it seems plausible that we sometimes do not want to do what we think we ought, Davidson argues, it seems just as valid to assume that when we truly think an action ought to be performed, we will act accordingly Davidson, 2001, p. 23).

How sincere is your belief in the ought?

In other words, if our belief in the ought is sincere enough, our desire will comply. What it comes down to, then, is whether motivational internalism or externalism is true, i.e. whether judgment and motivation are intrinsically connected or not. But since this question is related to a separate, meta-ethical debate, with adequate arguments on either side, I shall not discuss it further in this essay.

To summarize, while both Watson’s and Davidson’s position on the truth of P1 and P2 are ultimately up for debate, we may at the very least conclude that Watson’s third critical question — considering the reviewed arguments undermining his view — does not strike a decisive blow against Davidson’s theory.

Conclusion: ‘Not a decisive blow …’

Although Davidson seems to have solved the incontinence paradox by postulating a logical disconnection between conditional and unconditional judgments, Watson nonetheless criticized the philosopher’s proposal by presenting him with three challenging questions.

This essay set out to defend Davidson’s account by reviewing and deflecting these points of criticism.

The first question expressed skepticism with regards to the soundness of the conditional-unconditional distinction.

I countered the allegation by indicating a potential metaphysical difference between the two kinds of judgment. While the topic certainly requires far more nuance, denying any distinction is, as far as I am concerned, incorrect.

The second question, then, suggested it was possible for people to act against their unconditional judgments. Although this is technically a possibility, it simply does not make any sense. And as such, the question itself is deceiving.

The last question, finally, concerned the truth of P1 and P2. In response, I presented both Socrates’ and Davidson’s arguments in its favor.

I explained that, while we cannot definitively demonstrate the premises’ truth, it seems that Watson, likewise, cannot prove the contrary with any more force. And so his third question too does not strike a decisive blow against Davidson’s theory concerning weakness of will.

- Davidson, Donald. (2001). “How is Weakness of Will Possible?” In Essays on Actions and Events, 21-42. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Gardner, Thomas. “Socrates and Plato on the Possibility of Akrasia.” The Southern Journal of Philosophy 40, no. 2 (June 2002): 191-210.

- Mason, Andrew S. (2014). “Plato’s Metaphysics: the “theory of Forms”.” In Plato, 27-59. New York: Routledge, 2014.

- Watson, Gary. “Skepticism about Weakness of Will.” The Philosophical Review 86, no. 3 (July 1977): 316-39.

Notes

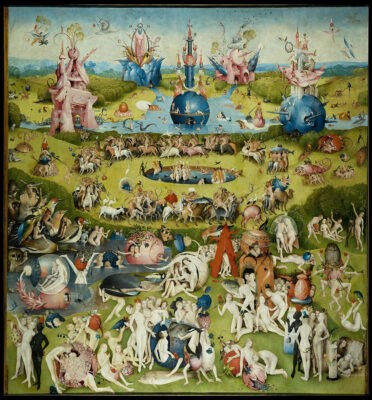

[1] Source in the Public Domain of The Garden of Earthly Delights center piece — in the Museo del Prado in Madrid, c. 1495–1505, attributed to Hieronymus Bosch.

[2] Source in the Public Domain of Battle of Potidaea Socrates saving Alcibiades (detail) — Athenians against Corinthians, 431 BCE; Socrates saves Alcibiades Engraving (sketch) by Wilhelm Müller after the drawing (detail, 1788) — by Jakob Asmus Carstens (1754–1798). From: H. Riegel, Carstens Werke, 2nd ed., Leipzig 1869. Berlin, Sammlung Archiv für Kunst und Geschichte.

[3] Source in the Public Domain of a fresco depicting Plato — Leonardo da Vinci as Plato, detail of The School of Athens by Raphael(1483–1520) by Raphael, circa 1509-1510, fresco, Collection, Vatikan, Stanza della Segnatura, Rome; Source/Photographer The Yorck Project (2002) 10.000 Meisterwerke der Malerei (DVD-ROM), distributed by DIRECTMEDIA Publishing GmbH. ISBN: 3936122202.

[4] Note that I do not intend to draw some analogy in the strictest sense of the word. Plato’s view has been criticized thoroughly throughout history, and my aim is not at all to defend his position. In fact, the reference to Plato’s theory purely serves a clarifying role here.