By Greg Suffanti

QFWF no. 3, April 2018

Great compassion

“To actually gain the wish for enlightenment (a person) must first contemplate it. To contemplate it, (a person) must first learn about it from another. “Loving-Kindness” is an almost obsessive desire that each and every living being find happiness. “Compassion” is an almost obsessive desire that they be free of any pain.

Think of how a mother feels when her one and only most beloved son is in the throes of a serious illness. Wherever she goes, whatever she does, she is always thinking how wonderful it would be if she could find some way of freeing him quickly from his sickness. These thoughts come to her mind in a steady stream, without a break, and all of their own, automatically. They become an obsession with her. When we feel this way towards every living being, and only then, we can say we have gained what they call “great compassion”, or Bodhicitta.[1]

Obvious joy and genuine happiness

There are basically three types of Buddhism: Theravada Buddhism, in which the practitioner strives for personal liberation; Mahayana Buddhism, in which the practitioner strives for the liberation of all sentient beings; and Vajrayana Buddhism, which is an extension of Mahayana Buddhism, relying on Tantric practices. (In Sanskrit, Vajrayana means “Diamond Vehicle”).

When I first became interested in Buddhism, to be honest, these sorts of distinctions weren’t clear in my mind at all.

Before I started taking classes at Maitreya Instituut in Amsterdam in September of 2000, I was living in Seatle, WA. and was reading books on Buddhism as I was growing increasingly disillusioned with my job as the director of the Seattle branch of a national company.

I was finding the corporate world unsatisfactory, and my unhappiness seemed to grow each day as I searched to find some meaning in my life other than achieving capitalistic goals.

The catalyst for this new-found interest was seeing His Holiness the Dalai Lama on a former CNN television program called “Larry King Live”. I remember being transfixed to the TV screen, almost mesmerized by His Holiness’s presence, and deeply moved by his obvious joy and genuine happiness. I became curious to find out how this was possible, and more importantly, if this was possible for me.

Om Mani Padme Hum

One of the first books I bought was “The Heart Treasure of the Enlightened Ones”[3], which is a discourse on the path to enlightenment, as well as an explanation of the mantra of compassion, Om Mani Padme Hum, by Patrul Rinpoche, with a simple and clear commentary given by His Holiness Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche. I still carry this book with me wherever I go, and am always inspired by these great masters’ advice that reciting Chenrezi’s (the Buddha of Compassion) mantra, Om Mani Padme Hum, is “the essential meaning of all eighty-four thousand sections of the Buddha’s teaching.” [4]

For Buddhists like myself, His Holiness the Dalai Lama is Chenrezi in human form, and I really appreciate living in a time when His Holiness’s teachings are available and just a click away on YouTube. What I’ve always liked about Buddhism is that it doesn’t ask you to believe in anything, and in fact the Buddha’s dying words were “don’t just believe what I say because I’m the Buddha.” The Buddhist practitioner is always encouraged to decide for him/herself if something is valid or not, and most importantly, if there is benefit (or not) for one’s own mind. For me, the simplicity of reciting the “mani” has been a real help in distracting and calming and stabilizing my usual “monkey mind” and allowed me to gain some valuable insight into my own deluded thinking.

I’ve often been overwhelmed by the vastness of the Buddhist canon, and have struggled through the years (although increasingly less so as I see and experience the benefits to my mind) with my own, self-chosen daily commitments. It has taken these twenty years to be thankful for the different initiations and teachings I’ve had and to appreciate the rare opportunity to have had some of them from great masters like His Holiness the Dalai Lama, Kyabje Lama Zopa Rinpoche and Khensur Rinpoche Geshe Lobsang Delek.

I take great comfort in Patrul Rinpoche’s root text when he says:

“The mind cannot cope with all the

Many visualization practices;

To meditate on one Sugata (Buddha) is to

Meditate on them all” [5]

Cultivating Bodhicitta

Anyone who studies Mahayana Buddhism can tell you that the goal for all practitioners is to work at cultivating Bodhicitta so that one becomes a Bodhisattva, or someone who strives solely for the benefit of others. My own root guru, Geshe Ngodrup, says, “the Bodhisattva’s main aim is achieving the aim of others, not Buddhahood.”

This noble wish can sound so simple, and His Holiness the Dalai Lama often says, “Bodhicitta, or the good heart”, making the entrance to the Bodhisattva path something accessible to just about everyone. The Bodhisattva attitude becomes more difficult (at least for me) when considering that this altruistic wish to work for others’ benefit includes ALL sentient beings. So, this includes tyrants like Bashar al-Assad, racists of all sorts, bigots, and all the members of Isis as well as all other murderers and rapists. When I consider this, I know I’m a very long way from having actual Bodhicitta.

In 2009, I had a major burnout. I had already been working full-time for seven years doing nightshifts as a caregiver, and had recently started a part-time job caring for a young man dying of ALS, or Lou Gehrig’s disease. My father was seriously ill (he died in January of 2010) and I’d lost my best friend in 2007. I was struggling with chronic fatigue (due to chronic illness) and another close friend had moved to a Greek island. I was also suffering from depression and loneliness.

First, we must determine what our biggest problem is

Early in 2009, we hosted a visiting Lama named Geshe Sherab, at our center in Amsterdam. The weekend course was entitled “Seven Point Thought Transformation”, and this weekend course would impact my entire life. My burnout had been building all through 2008, and even though I thought I was “doing the right thing” by trying to help others, in hindsight, my motivation was more ego involved than anything else. That’s why Lama Zopa says that “without Bodhicitta motivation, we don’t get any fulfillment or satisfaction in our heart, even if the good service and work we’re doing is very practical and beneficial for others.”[7]

I remember very little from Geshe Sherab’s course, but I clearly remember his repeating over and over that “first, we must determine what our biggest problem is.” Here I am, studying Buddhism for years, working as a caregiver in Amsterdam, rather than as a successful businessman in America, supposedly cultivating love and compassion in everything I do, and I’m hit, as if by lightening, by the sudden realization that I don’t even like myself. How can I have love and compassion for others when I only have contempt for myself? The answer, of course, is that I can’t.

By April of that year my back went out, as it did every three months or so, only this time it was different; I left my nightshifts for good and fell completely to pieces, as anyone whose had a burnout can tell you. I scarcely left the couch for the next six months, although I continued to work at my part-time job, putting on a smiling face and pretending that everything was okay. It wasn’t.

Avoiding all extremes

In the Netherlands, everyone has healthcare, and everyone has a right to help for all kinds of problems, from financial to health to mental health issues. I was referred by my doctor to a psychologist, Dr. Mieke Fleury, whose great kindness and openness touches me to this day. When I told her I was working both full and part-time as a caregiver, plus studying and working as a volunteer at a Buddhist center she pronounced, “you have no pleasure in your life!”

I had totally disregarded the basic Buddhist advice of avoiding all extremes. I’d had a lifelong habit of being a perfectionist and rationalized this unhealthy approach to life by reiterating to myself, almost daily, that this way of being had gotten me through Yale and allowed me to become the director of a multi-million dollar company by the age of 33. Now that I’d chosen to live in Amsterdam, my strident ways had allowed me to work multiple jobs, learn Dutch and study Buddhism. The fact that I was never happy was irrelevant, because like most perfectionists, I saw nothing to be happy about. I only saw my perceived endless faults and mistakes. So much for my first decade of being a Buddhist!

Although I stopped working full-time (I started receiving an income based on my salary), I kept my part-time job as I told myself I was needed. This was true, but, it was also true that I was terrified of not working at all and being truly alone in life, with nothing to fill the many hours of each day. I continued my therapy, and tried each day to see how the many negative attitudes I had toward myself were only holding me back.

Mieke would often remind me that the way I viewed myself was not only unhealthy, but not based in any sort of reality, as no person I knew shared this negative view of me. Still, I often saw myself as a failed loser. The burnout felt like incontrovertible proof that I was capable of nothing of worth and that I was evolving into a bitter, middle-aged blob.

Work on our inner teacher, developing a dialogue with one’s self

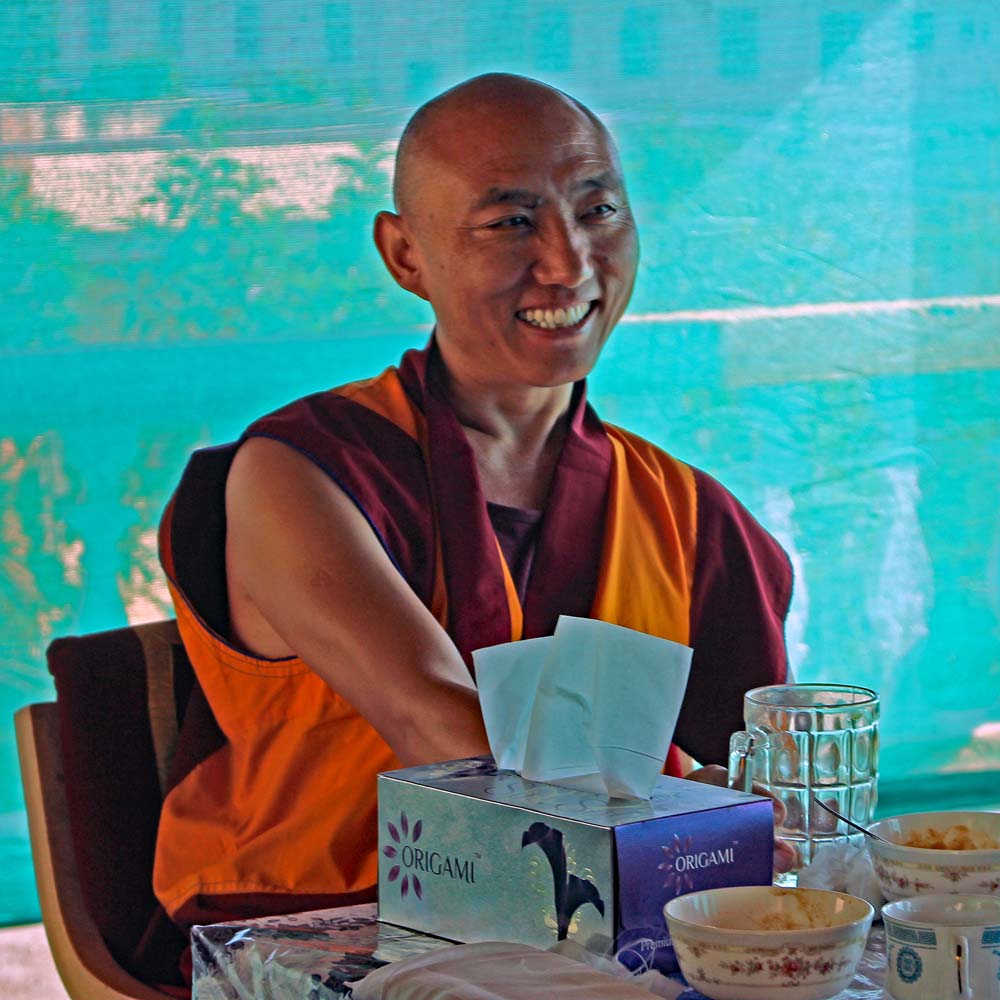

In the summer of 2012, Lama Zopa Rinpoche, the spiritual director of the mother organization to which Maitreya Instituut belongs (the FPMT), asked Geshe Ngodrup to leave his position as a teacher at Nalanda monastery in France, and come to teach at the Maitreya Instituut in Holland.

Maitreya has two centers, one in Amsterdam, and one in Loenen, which is about an hour’s drive from Amsterdam. The center in Loenen is much larger.

Both Geshe Ngodrup and his translator from Tibetan into English, Khedrup, arrived in August of that year. I remember, because our center director, Paula de Wys, asked me to take them to lunch one sunny and warm afternoon. Khedrup and I (to use an American expression) got on like a house on fire, however, I found Geshe Ngodrup rather small and sickly and so quiet I remember thinking, “he won’t last a year.”

Well, without my even realizing it, after a year of attending Geshe Ngodrup’s classes, my heart and mind were being touched in a way that I had never experienced before.

By the second year, Paula asked me if I could host the two of them once a month, as Geshe Ngodrup was teaching in Amsterdam.

I have a guestroom and live close to the center and so I readily said yes. By this time I had accepted Geshe Ngodrup as my teacher, and eventually, I would come to regard him as my root guru. It was the greatest honor of my life to be able to host “my Lama” in my own home. Through my experiences with Geshe Ngodrup, I could see and feel his loving kindness and I could feel the beginning of a profound inner change as well.

Set time aside every day to cultivate positive mental qualities

His tremendous intellect inspired awe in me and it was also obvious that he was a true Buddhist practitioner. It was his gentle urging to “seek compassion for others through understanding my own situation of suffering” that finally allowed a healing process to start within me. He was always encouraging us to “work on our inner teacher, developing a dialogue with one’s self.”

Geshe Ngodrup described Bodhicitta as being “like a kind father who takes care of all his children.” I was slowly changing, and slowly my heart was opening to myself and others. He encouraged all his students to “set time aside every day to cultivate positive mental qualities,” adding that “stable effort can bring great results.”

This quiet, humble teacher was slowly helping me towards the most profound inner changes I’d ever experienced.

I took refuge with Geshe Ngodrup in the fall of 2013, and ten days later I suffered a stroke. A good friend of mine, who is a Buddhist and an astrologist, said, “that’s great! Your taking refuge with your teacher has cleared some big karmic knot out of the way!”

As strange as it may sound, I’m thankful for the stroke, because I’ve become a much happier person these last few years. The stroke showed me how life can end at any moment, and that the only worthwhile goal in life is to be happy and to try to help others.

I tried (and still try) to follow Geshe Ngodrup’s advice, and soon I was waking each day, cultivating gratitude for still being alive and trying to broaden my love and compassion towards others.

Unconditional love and acceptance

My worst nightmare had come true, and I could no longer work, however, I had my precious teacher to help and inspire me each day to cultivate loving kindness … for all beings, including myself. Understanding my own suffering has been the path for me to see the suffering in others, and to naturally feel compassion for them.

Slowly, slowly my heart was opening and for the first time in my life I began to see myself as worthwhile and worthy of love. For the first time in my life I felt happy. It was like magic, and Geshe Ngodrup’s teachings became like an ambrosia of loving warmth, cradling me safely as I grew and changed. Geshe Ngodrup’s unconditional love and acceptance have opened my eyes and my heart to the realities and joys of true love and true compassion.

This is Bodhicitta and Geshe Ngodrup is a real Bodhisattva to me. Sadly, his chronic illness became worse through 2017, and after five years of teaching off and on in Holland, he was forced to return to India to try and get better. His loyal translator, Khedrup, also travelled to India with Geshe Ngodrup, to help him in his hour of need. Although my precious teacher is physically thousands of miles away, his teachings and his genuine love and compassion live indelibly in my heart… hopefully forever.

To see all beings as one’s own mother

In Mahyana Buddhism students are encouraged to make efforts to feel close to all living beings. It is often advised to see all beings as one’s own mother. As this is problematical for some people, especially in the West, it is advised to use the person to whom you feel closest, and start from there.

I’ve been in America for the last month, helping my mom move to a senior living community. She’s lived in the same house for more than fifty years, and there is still much work to be done. My (identical) twin brother has also lived in this house for the last nineteen years, so I’ve been helping him move as well.

He has found an apartment much closer to his work and his girlfriend, and like our mom’s move, it is a time of happiness and joy for them both. They are both thrilled with their new living arrangements.

It has given me indescribable joy to be able to help, especially my soon-to-be 84 year old mom, and to try to pay her back for the countless ways she has helped me and supported me as a single mother through the years. Although we were never rich, my mom did everything she could think of to support me, including working both full-time and part-time to help put me through Yale. She has never asked anything of me, not even to come and visit her these last couple of years, when I chose going to teachings in India, instead of coming to America to see her.

Struggle with Bodhicitta

Through the last twenty years of calling myself a Buddhist I think I’ve struggled (and still do) the most with Bodhicitta. After weeks of packing and unpacking and cleaning and giving away things to charities, I go to sleep and wake each morning wracked by pain. After a long day, even thinking or walking is an exercise in yet more pain.

And I’ve never been happier or more fulfilled in my life! I feel boundless energy and determination each day to help these two people I love achieve their goals, helping their dreams become a reality. I finally feel like I’ve actually touched Bodhicitta, just a little bit, trying to help someone else be happy and not worrying about how I feel.

How can I not be thankful to those who’ve taught me and helped me and showed me the path to genuine happiness? How can I ever really pay these kindnesses back?

If I can take a little bit back to Holland from these experiences here in America with my mom and brother, I’ll have taken yet another baby step forward in my growth as a Buddhist and as a human being.

Thank you dear reader for reading my simple story.

Thank you to my family and teachers for giving me a story to tell.

Notes

[1] Geshe Lobsang, T. & Roach, M. (1998). Tsongkapa, The Principal Teachings of Buddhism. Howell, New Jersey: Mahayana Sutra and Tantra Press, p. 97

[2] Source: maitreya

[3] Rinpoche, Patrul & Rinpoche, Dilgo Khyentse (1992). The Heart Treasure of the Enlightened Ones. Boston, Massachusetts: Shambala Publications.

[4] Rinpoche, Patrul & Rinpoche, Dilgo Khyentse (1992). The Heart Treasure of the Enlightened Ones. Boston, Massachusetts: Shambala Publications, p. 58

[5] Rinpoche, Patrul & Rinpoche, Dilgo Khyentse (1992). The Heart Treasure of the Enlightened Ones. Boston, Massachusetts: Shambala Publications, p. 85

[6] Source: Geshe Thubten Sherab

[7] This excerpt is taken from Lecture Six and Lecture Seven at the 28th Kopan Course in Kathmandu, Nepal, 1995. Read: www.lamayeshe.com/article/kopan-course-no-28-1995-audio-and-transcripts

[8] Source: Photo on a 2016 trip to Sera Monastery in Bylakuppe (Karnataka, India)

[9] Source: Photo on a 2016 trip to Sera Monastery in Bylakuppe (Karnataka, India)

[10] Source: Photo on a 2016 trip to Sera Jey Monastery in Bylakuppe (Karnataka, India)

[11] Source: spring flowers