By Greg Suffanti

QFWF, quest book no. 1, May 2018

Chapter 1: “Always Do What You’re Afraid to Do”

Ralf Waldo Emerson

American Dream

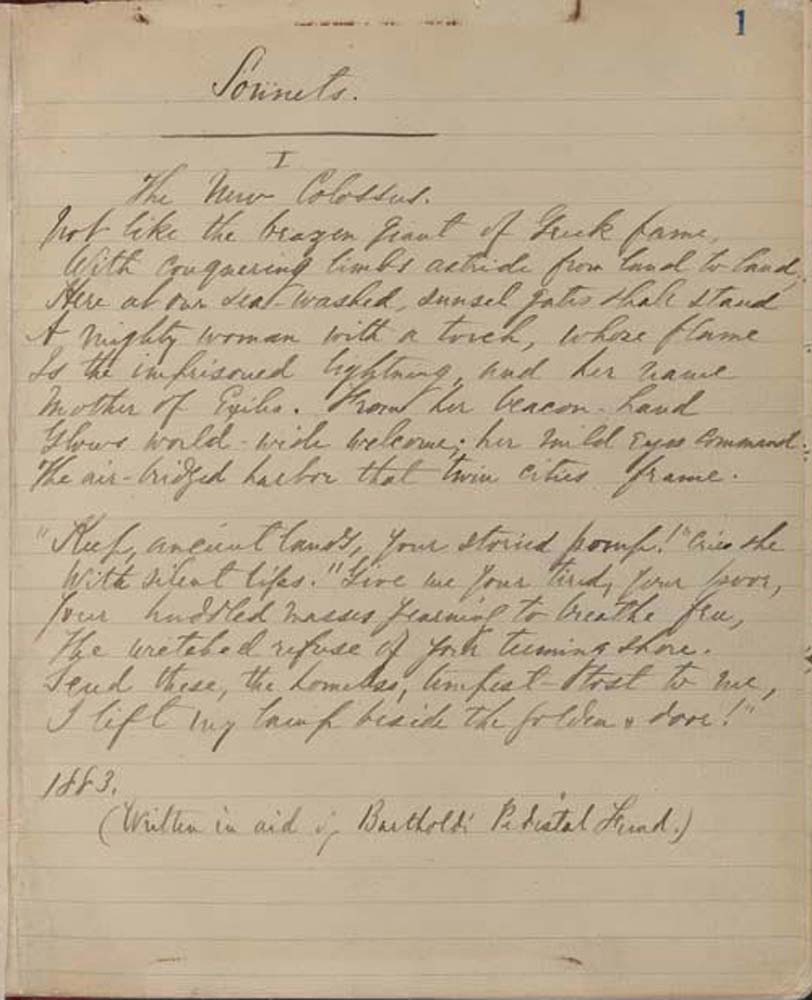

The poem at the base of the Statue of Liberty in New York Bay, called “The New Colossus”, has always been an inspiration to me.

The poem reads:

The New Colossus

“Not like the frozen giant of Greek fame,

With conquering limbs astride from land to land;

Here at our sea-washed, sunset gates shall stand

A mighty woman with a torch, whose flame

Is the imprisoned lightening, and her name,

Mother of Exiles. From her beacon-hand

Glows world-wide welcome; her mild eyes command

The air-bridged harbor that twin cities frame.

“Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!” cries she

With silent lips, “Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tossed to me

I lift my lamp beside the golden door.”

by Emma Lazarus in 1883

Both my mother and father had immigrant parents, from Poland and Italy, respectively, and I grew up hearing Italian spoken on visits to family in Brooklyn and Polish in the suburbs of Pittsburgh.

The idea of a land offering refuge to those who sought the safety of true democracy and the promise of a bright future, especially welcoming the unwanted of the world, seemed to me to be amongst the very noblest of aims in all of recorded history.

I grew up living and seeing and believing in the “American Dream”. My family lived well and we lived the American dream. It was private schools, private planes and private clubs when I was growing up. For me, America was a noble land, founded on noble traditions; a place where anything was possible. Truly, “the promised land”.

Then I got sick.

I never realized how American I felt and how much these sentiments meant to me until I left America for good at the beginning of the 21st century for “the storied pomp” of Europe: “the old country”.

The Kingdom of the Netherlands

At the beginning of 2000, I flew to Amsterdam from Seattle to start a new life as a healthcare emigrant; an HIV/AIDS refugee/emigrant. I had never imagined my life would take such an unwanted and unexpected turn, yet I was now grateful that a safe harbor was possible for me in the Kingdom of the Netherlands.

I had no job and no place to live. What I had was a dream to live and die in a country which did not regard me as either a freak or mentally ill, or both. I had never thought of living in Holland, and had visited this tiny country in September of 1998 for the very first time. I fell unexpectedly in love with Amsterdam during that visit. For a gay man with HIV/AIDS, Holland’s tolerant ways represented the “promised land” and Amsterdam, with her timeless beauty and vibrant gay life, was her doting, caring, and accepting mother. No questions asked.

Equal citizen, protected legally

In Holland I’d be considered an equal citizen, protected legally. Suddenly, these rights felt essential to my sense of fairness and equality, and so I told myself, that if I was going to die young, then I wanted to die in a country that legally saw me and protected me as one of her own. It wasn’t pity I was looking for, it was equality under the law. Money gave me the luxury of choice, and for me, the only choice was Amsterdam.

I’d probably never reach forty…

At the time I had no expectations that I would live for any great length of time, as the first four years of my HIV treatment had produced one medical failure after the other. The drugs then available simply didn’t work for me. Unfortunately for me, it would be fourteen years before I’d find ones that did. I felt sick all of the time and didn’t need a doctor to tell me I’d probably never reach forty. I felt no anger towards America, with her caste system of healthcare access and her forever changing views and judgements on being gay.

When I moved to Amsterdam, there was no LGBT movement yet in America, there was the struggle during the 2nd half of the 20th century for gay men and women to come out of the closet and live their lives freely and openly. More than anything else, I felt truly fortunate to be able to move to a country with a more generous and equitable social arrangement: a system which included healthcare for all of her citizens and an Equal Rights Law, passed in 1994, which banned discrimination in the work place, housing and public accommodation based on sexual orientation.

Amsterdam was then the gay capital of the world

Amsterdam was then the gay capital of the world, and with the dawn of a new century, the Netherlands became the first country in the world to allow same-sex marriage in 2001. I had grown up during the 60’s and 70’s, a time in mainstream America when people didn’t talk about things like being gay, or for that matter, gay rights, let alone a LGBT community, so, moving to Amsterdam felt like a giant coming-out party… a celebration in which I was being invited to join the human race as just another fellow human being for the very first time.

I’d not realized what conservative American provincialism had done to my psyche until I’d smelled the fresh air of true equality and freedom in the Netherlands. I longed to see myself as just like everyone else; not different because I happened to like guys and also happened to be a guy or happened to be sick. Hope and optimism filled me with the promise of a genuine future.

The doctors in Amsterdam said exactly what the doctors in Seattle had said (except in Dutch): “be prepared to die young”. As much as I felt death lurking restlessly inside of me, trying to pull me down and consume me, I was determined to never give up on myself. It was exhilarating to be living in Europe and be confronted with learning a foreign language and a new way of life.

I had finally come home

I was intoxicated by the beauty of Amsterdam, with her canals, narrow, twisting side streets, old buildings, charming cafes and coffee shops, where people met and smoked marijuana and listened to music. I felt alive again. It was easy to forget I was dying with so much life and beauty around me. Nobody cared whether I was gay or straight, it was more like the difference between having brown eyes or blue eyes. I was never looking to make a statement with my sexuality, and certainly not with my illness. I had finally come home.

I would be starting all over again, at 35, leaving my past behind as well as my qualifications and my very upwardly mobile middle-class way of life. For anyone that didn’t know I was sick, it would’ve appeared as though I was crazy to be throwing away all I had worked so hard for.

It was Holland that was offering a “wretch” like me some sort of future, some sort of acceptance as an equal human being; and within her vast social services network, a chance to live with dignity, no matter how bad my personal situation got.

No Lady Liberty to catch my fall

I had lived the American dream, but when I fell, there was no Lady Liberty to catch my fall; only the prospect of falling into a hopeless tailspin of poverty in a land where the survival of the fittest is packaged and sold as the superior form of capitalism that is said to be the envy of the world.

America still seems to have no appetite for the personal tragedies of the uninsured; no real social net to catch and cope with the “wretched refuse” of those whose lives are economically challenged and devastated or destroyed by illness.

Even now, the debate over medical insurance rages on in America. How long can America remain the only industrialized country in the world that doesn’t offer all her citizens universal healthcare coverage? Going on Medicare and living in 2nd class public housing was not a future I could embrace.

Once upon a time,

I had been the American dream, becoming the first in my family to graduate from university: Yale University (1987). I had a senior management function in a fast-growing private (now public) company and I was a rising star, even if I do say so myself.

I lived with my handsome partner in a three bedroom house in a charming West Seattle suburb, drove a new car and had even worked as a model in my younger years in New York, Washington, D.C. and Miami.

My future was set, and I had the looks, clothes, partner and fast-track career to prove it. I thought of America as the greatest nation on earth. Then I got sick.

Eventually, my expanding company wanted me to move and head up the expansion effort in Charlotte, N.C.. My beautiful partner had not only developed full-blown AIDS, he’d fallen in love with someone else. My heart broke with his AIDS diagnosis and now felt broken again with the news of his new love.

I was permanently blindsided by my ever-changing new world, as if I’d never get secure footing again. Total secrecy was my new norm. Along with the HIV/AIDS drugs then available came the side effects of feeling perfectly awful all of the time. I felt constantly that I was being eaten alive from the inside out, and I started gaining weight from the HIV drug “cocktails” which I took every four hours. My world as I knew it was over.

The shock of that moment

I was called at work one sunny, mid-September afternoon in 1996 by a doctor at the Harborview Medical Center in downtown Seattle, who informed me that my partner had been admitted with PCP pneumonia, an AIDS-defining illness. I’m not sure how or even when I ever fully recovered from the shock of that moment. He said it was serious, and that Peter had only a 30% chance of surviving.

He then unceremoniously added that “there is no chance that you’re not HIV positive”. I remember just staring at the wall in my office for a long time, doodling mindlessly on the calendar, too stunned to move. In the span of that short phone call, my life changed forever.

Peter and I were monogamous and had been together eight years at the time of his diagnosis. The news shook me to my core and would ultimately be the impetus for me to change the course of my life. At the time it felt like a shameful death sentence to be carried out in absolute secrecy. Nothing was scarier than AIDS. How do you prepare to die when your life is just getting started and you’re both dying?

Ashamed of myself

The whole situation felt so fantastically unreal, except that I too had been feeling ill for some time. The prospect of falling into further illness and poverty became my very real future. There was no cure for HIV/AIDS and it would only be a question of time before I would be too ill to work. I began to feel diseased and ashamed of myself. Doctors now wore gloves and masks with me and talked to me about having to make peace with my prognosis. I’d sometimes fall asleep softly crying and wake the next morning still crying.

Peter recovered and came home after 4 weeks in the hospital. If you ever want to know how to get a private room in a hospital it’s called AIDS. He was put on the prophylaxis Bactrim. This simple measure would keep Peter from getting PCP pneumonia again. It would help him to go on until his death in 2001 at the age of 34 from complications from AIDS.

Many thousands of young, mostly gay men would die needlessly in the 1980’s as the gay community struggled to get out the message that some AIDS illnesses were preventable. By the 1990’s, cities with large gay populations had doctors specializing in HIV/AIDS and information centers explaining how to get on Medicaid and other social services “when the time came.”

Just Keep Walking

The Johnny Walker Whiskey ad campaign that states, “Just Keep Walking”, became my mantra. I repeated this mantra to myself both verbally and visually, daily, for many, many years until I heard the call to keep going in the deepest reaches of my conscience.

There was never a moment of peace. For there wasn’t any room in my life, which was now too full from the terror of the realities of HIV/AIDS and the awareness that my and my partner’s lives were slipping away just when they seemed to be starting.

I saw myself as wholly toxic and diseased and unworthy of love. I buried myself in work and thrived in my successes there. I briefly lamented the feeling of hollowness each new success brings, but I reassured myself that with the next promotion things would get better. I’m forever searching for something to make all of my misery go away.

I increasingly relied on the prescription painkiller OxyContin (the painkiller OxyContin was falsely introduced by Purdue Pharma in 1996 as a non-addictive alternative to morphine). The OxyContin kills the symptoms of the HIV, the side effects of the HIV medicine, and my deep emotional pain at this most unwelcome turn of events in my life. It allowed me to continue to work as though everything was just fine and dandy.

With addiction added to my life, I was now fully becoming everything I never wanted to be in life and more. I saw no way out and no future. I could feel my energy becoming weaker in a way I’d never experienced before: this was what a slow death felt like.

“Who the fuck wants to go to Holland!?”

With my increasing inability to find a reason to hope for something positive, my will to live was being tested to the very core of my being. I was left asking myself, “how will I go on, and what is going to happen to me?” A feeling of desperation was my constant companion and I nearly exploded inside from the sheer weight and magnitude of my problems.

Something had to change. Soon. Peter wanted to rent a car and then spend a month driving around France and Spain, just as “friends”. He decided to rent the car in Amsterdam because it was half the cost of either Paris or Madrid. I remember my angry reaction to this day when I barked at him questioning, “who the fuck wants to go to Holland!?” Little did I then know.

Nothing was the same in my new world

Nothing was the same in my new world of HIV/AIDS, and in the quieter moments, I began wondering when Peter would die. In the following months, I saw the KS cancer lesions on his body appear and we’re both afraid he’ll “show”, that the world would see another AIDS victim, with the white, translucent skin and the sunken cheeks and blank, staring eyes. It was 1996, just after the height of the AIDS epidemic, the year after the most (46,000) AIDS related deaths in America.

I thought things like this happened to other people. I was no whore, no drug addict. I’d had unprotected sex in the 1980’s and studies were showing that the incubation period before the virus became active was up to seven years and sometimes even longer. There was no time and no room for blame and no way to ever know who infected who.

The prospect of both Peter’s and mine early deaths became the beginning of my great secret. The only small consolation seemed to be that I now understood why I felt so awful all the time.

When I said goodbye to him in Seattle, it was to be a final goodbye.

(To be continued…)

Notes

[1] Source: New Colossus manuscript Lazarus Statue of Liberty, Liberty Island, New York City, New York, U.S. Purpose: To raise money for the statue’s pedestal’s construction

[2] Source: smalle steegjes Amsterdam

[3] Source: Amsterdam rainbow coffeeshop

[4] Source: kleinste huis Amsterdam

[5] Source: Johnnie Walker by Bloom and Anomaly